A Big Publisher Accepted My Novel—Then Rejected It Because I Used AI

Tradeoffs in using LLMs for writing

The renowned anthropologist Renato Rosaldo has this book where he reflects on the sudden death of his wife Shelly and through those reflections reaches deep ethnographic insights about the Ilongot, the indigenous people the couple were studying at the time of the tragedy. The book uses poetry as a kind of ethnographic record and its writing was his way of dealing with his grief. The book is weird and beautiful.

I have this perverse but scholarly desire to be ostracized because of my use of AI, and my admiration for Rosaldo as well as war correspondents like Sebastian Junger might be its source. Taboo and the sacred are part of my scholarly interest, and you can’t deny that a reportage from within the experience of the dangerous frontlines could also be weird and beautiful.

I’ve witnessed the formation of this new taboo in the more literary corners of Substack, perhaps a year or so after the rise of the taboo against AI-generated images from the community of visual artists. I’ve also noticed a bit of shame within me (I’m not a psychopath despite writing a lot about them). I’ve anticipated this tradeoff when I started using Claude for my novel. This tradeoff still makes sense. The unassisted chapters took an average of a month to complete, while the AI-assisted chapters averaged around a week. So it would have taken me four to five years to complete the novel instead of fifteen months. I essentially exchanged time for status. The world will never recognize my literary genius lol.

It wasn’t just time in exchange for status. My ambition was in weaving memeplexes within a story most would enjoy, not pushing the boundaries of language. The latter, I sense, is the measuring stick of award-winning literary fiction in the Philippines. I had very definite voices in mind for the novel, but they were all conventional, nothing groundbreaking. LLMs are convention machines—this is why the tool fit my purpose. I was a control freak in which psychic megafauna to allow inside the story, as well as their hierarchy. In contrast, I was quite permissive at the sentence level. After writing four chapters, Claude had a sufficient pool of samples to translate my fragments and rough outlines into good enough sections. Since robots don’t get tired, I had it produce variations until it hit a jackpot. Many times, I had to combine smaller jackpot paragraphs then do the finishing touches manually. If I were a poet or a Filipino literary fictionist, this process wouldn’t have made sense. Thankfully, I’m neither. So the tradeoff was also letting go of sentence- and paragraph-level control, so I could focus on memeplex- and plot-level orchestration.

It would have been more impressive of course if I controlled all the levels. One of my favorite sci-fi writers, Ted Chiang, said in a speech that,

“If we think of art as a concentrated form of intention, then generative AI is a way of diluting intention” [...] “Making a lot of choices is hard work, but artistic self-expression requires that you make all the choices.”

Those of us who use AI should just accept the L. It’s a fair tradeoff. I avoid calling myself the novel’s writer. Author, creator, and producer are more accurate. I’ve always cringed at calling myself an artist, much more now. The novel—especially considering the speed of its creation—is not an authentic representation of my talents or skills as a writer. Why is this important, though? The answer lies in the same scholarly domain as my feelings of shame.

The sociologist Pierre Bourdieu had a term for this kind of shame—or rather, for the apparatus that produces it. He called it habitus: the dispositions we acquire through years of socialization, so deeply ingrained they feel like instinct. Habitus lives in the body. It’s what makes a working-class kid feel out of place at an elite university even when no one has said anything hostile. It’s why I cringe a bit when I tell other writers I used Claude, even when I believe my reasons are sound. This is also why I feel a slight annoyance when readers quote the robot’s bangers instead of mine.

I’ve been developing my own approach to the study of culture—a neo-animist approach which I call “Psychofauna Studies.” In this framework, large cultural forces like nations, religions, and literary communities are not lifeless abstractions but psychofauna—creatures that emerge from the substrate of human minds, competing for our attention and shaping our behavior for the sake of their own replication. Societies utilize the habitus within each of us to get what they want: their own survival and growth.

While I was working on the novel, I avoided literary communities. I knew they would be channels of psychofauna I’d have to protect the story from. They were unavoidable though once I started promoting the novel, but I did not see this as a problem. I felt that the story was safe since it was already written, and the scholar in me was eager to experience the frontlines.

I met my first literary kaiju at the Manila International Book Fair. The government body that promotes local literature gave me an indie author booth, and I spent several days deep inside the bowels of that psychofauna.

It was overwhelming. One hundred sixty thousand visitors pressing through corridors over five days, the air thick with the mingled breath of bibliophiles and the sweet chemical smell of fresh ink on bookpaper. Queues for popular authors snaked around booths and spilled into the aisles, devotees clutching books to their chests like sacred objects awaiting consecration. At the Wattpad-turned-paperback booths, teenage girls shrieked at the sight of their favorite writers—authors who had built empires on serialized romance, their fan bases dense enough to collapse the crowd control barriers.

I was a minor organ in this beast, but an organ nonetheless. People approached my booth asking for selfies and autographs—for the first time in my life—as if I’m some kind of celebrity. I felt the kaiju’s attention on me then, registering my presence in its vast nervous system, adjusting my position in its hierarchy of faces and names.

The hierarchy was visible if you knew how to look. The National Artists occupied the upper tiers, their book launches attended by television cameras and government officials. Below them, the award-winners and the commercially successful, their signing lines measured in hours. Then the mid-list authors, the first-timers, the self-published hopefuls—each of us arranged according to the kaiju’s logic of attention and replication. I watched fans genuflect before their literary idols, and I understood: this was the psychofauna feeding, each interaction a calorie of devotion that kept the creature alive.

The kaiju leaned closer. I felt it pressing against something inside me—that old shame, that cringe when I admitted to using tech instead of raw skill and talent, that instinct to measure myself against the authors with longer lines. It was adjusting my desires, tightening the screws of literary aspiration, reminding me what I should want and who I should envy.

I told the kaiju, “Get your hands off my habitus, you perv.”

Yet I’m only human. When Daniel Kahneman, the Nobel laureate author of Thinking, Fast and Slow, was asked if decades of studying cognitive biases had made him free of them, he replied that he was just as susceptible as anyone else. Similarly, even with my neo-animist framework—even while watching these psychofauna operate, mapping their feeding patterns, tracing their tendrils—I remain their prey. After several days inside the kaiju’s domain, my defenses softened. The creature’s influence became irresistible. My desires were being shaped by forces I could see but not resist. I wanted to be like those authors at the apex of the hierarchy—the ones with their Palanca awards, their megalaunches attended by television crews, their signing lines measured in hours. So I gave copies of my novel to one of the biggest publishers in the country.

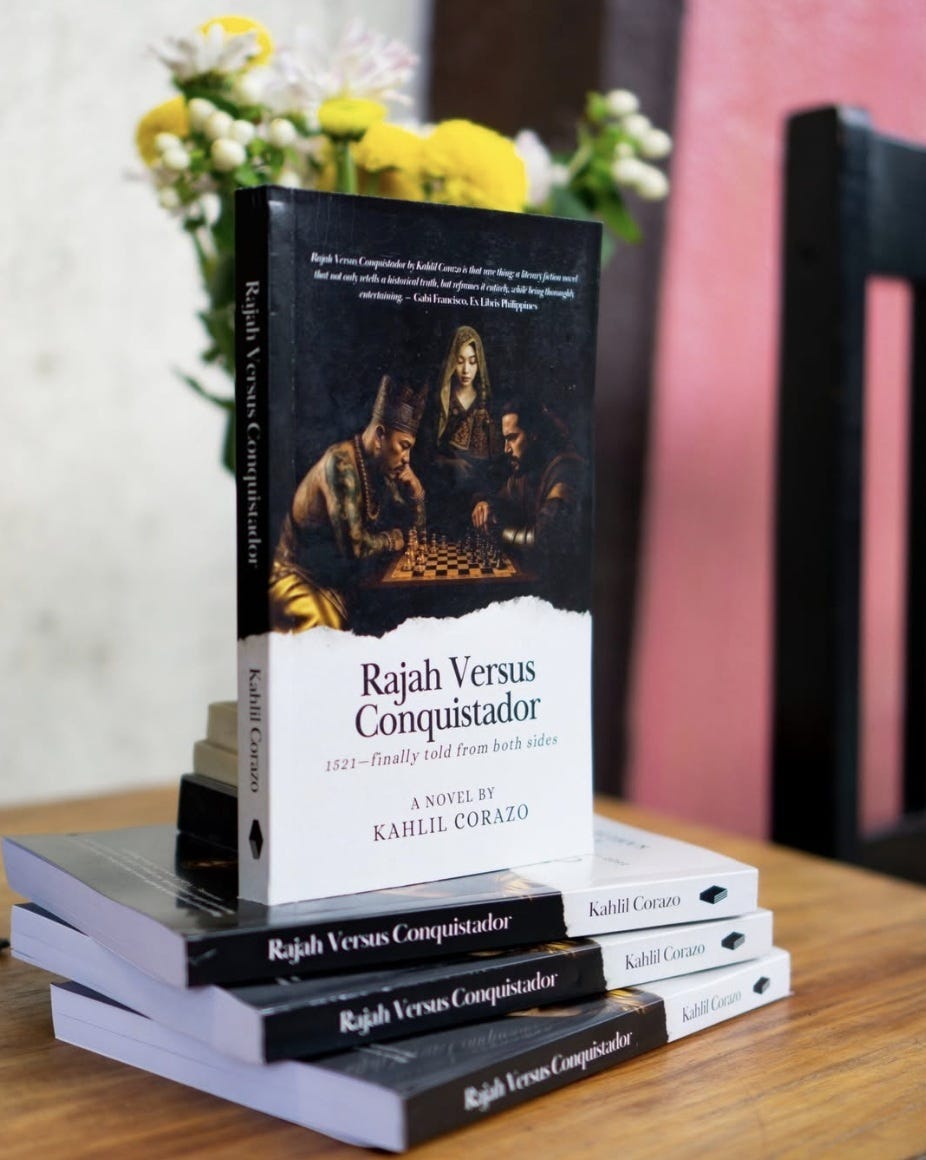

This was a reversal of everything I had planned. The indie path wasn’t just a business strategy; it was the authentic extension of who I was: Entrepreneur. Cebuano. A native of strange corners of the internet where conventional literary success was beside the point. Going indie was also an aesthetic choice, a thematic coherence with the novel itself. The protagonists of Rajah Versus Conquistador are a king and a captain—men who seized their own fates. Taking charge of my own commercial destiny was supposed to be an extension of their story, a refusal to submit to gatekeepers.

But I’d been exposed too long. The kaiju had seeded a little colony in my mind, and I found myself wanting what it wanted me to want.

I had done B2B sales in a past life, so I was familiar with the rhythms of pursuit: the follow-ups, the waiting, the constant threat of rejection hovering at the edge of every interaction. But businesses usually respond, even if only to say no. Philippine publishers, I discovered, operate differently. Sending manuscripts to them is like dropping messages into a void. The reply cycle is measured not in weeks but in months, if replies come at all.

A couple of months after, I met the head editor at the Frankfurt Book Fair—a much larger kaiju whose dimensions I will perhaps map in a future essay. I put on my most charming smile, and asked as casually as I could about their thoughts on my novel. In that vast belly of global publishing, she told me they liked the book. The owner had given a verbal yes.

More follow-ups. More waiting. Then an email telling me they’d like to meet. The Zoom call went okay—better than okay. They asked about details of the novel: the research, the historical sources, the metafiction. I was eager, perhaps too eager. I now have a wall of books arranged behind me for video calls—so stereotypical, I know—and during the meeting I kept reaching for volumes to illustrate my points, pulling down references on Magellan’s voyage, on pre-colonial Philippine society, on the figure of the Big Man. I have to be honest: I love this part of the job.

It was curious how they seemed unconcerned about my use of AI. In the literary corners of Substack, the taboo had already calcified into doctrine. But here was a major publisher, apparently indifferent. Perhaps the local kaiju of traditional publishing operated on different frequencies than the kaiju of online literary culture.

It turns out there was just a delay.

After more than a month and a couple of follow-ups, I received an email. Polite, careful, final. They remained interested in the story, but the use of AI had become something they needed to consider. They apologized for the earlier communications about approval and contracts. The door had closed.

Reading between the lines, I suspect I was their first. The gap between enthusiastic verbal approval and formal rejection had the texture of a policy being invented on the spot, deliberations happening in conference rooms where no one had yet established precedent. I became the test case, the boundary marker. I wonder how long they can hold that line—how many manuscripts will arrive in the coming years with AI fingerprints invisible to the naked eye, how many authors will simply not mention it.

I replied after a day—both the rajah and the conquistador who continue to live inside of me refused to let me wallow in disappointment. I thanked the editors for their consideration. And then, because the entrepreneur in me knows that a “no” is merely an invitation to try another door, I attached my older books: the nonfiction works I had written before the age of AI.

As I sent the email, I realized something: I got what I hoped for. The rejection was data from the frontlines of a cultural shift I had been observing online. I now had a story—a dispatch from the exact moment when the literary establishment drew its line in the sand.

I opened Roam Research, where I draft my essays. The cursor blinked. And I began to type: A Big Publisher Accepted My Novel—Then Rejected It Because I Used AI.

I appreciate you being upfront about it though. At least I don't feel tricked. I know what I'm getting into reading your novel and can compare the similarities and differences. I can observe how my body and mind reacts to it. No shortcuts to greatness doe. I think its taboo because of this belief.

The distaste for AI as a tool in literature is just a distaste for honesty about how much you used digital tools in the process. Short of locking authors in sealed rooms for the entire writing process there can be no certainty that AI didn't taint a book. The new policy among the publishers will only reward liars.