How the Diwata Got Me to Write a Feminist Novel Despite Being Steeped in Filipino Machismo

Neo-animism for creative work

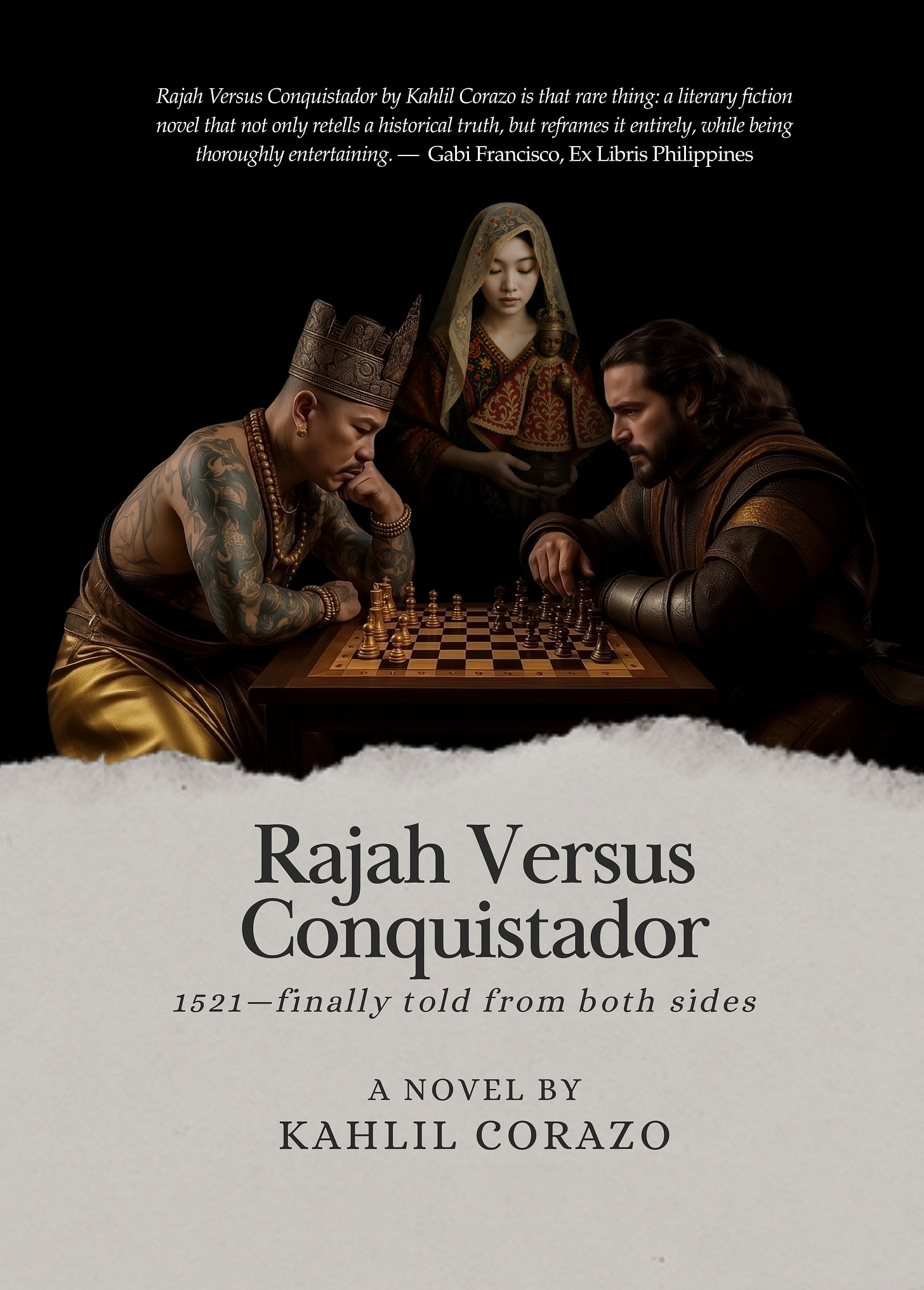

According to my records, she revealed her name in September, eight months before the release of Rajah Versus Conquistador, my historical novel that reimagines the power game between Rajah Humabon and Ferdinand Magellan, leading to the latter’s death in 1521.

By December, she showed me how she wanted to be introduced. I was in a downtown Davao coffeeshop called “Café Prelaya by The Joaquins,” where I’m also writing these words. This cafe’s name is part of the story, as you will see later.

Her name, Paraluman, was my little tribute to the Eraserheads, but it turned out to be more meaningful than just a pinoy rock easter egg. “Paraluman,” I found out, is an archaic Tagalog word for the magnetic needle used by our ancestors as a compass for navigating the seas. This was one of the many serendipities that happened within the story. In the middle of the novel, the recently baptized Paraluman carries the image of the Sto. Niño into the beach-side feast to celebrate the alliance between Humabon and Magellan. She then intones this hymn to the Niño:

Batobalani sa gugma, ang batâ namong palanggâ

Batobalani sa gugma, ang batâ namong palanggâ

Batobalani sa gugma, ang batâ namong palanggâ.

I grew up in Pari-an, downtown Cebu, a few blocks away from the Sto. Niño basilica. Whenever I hear “batobalani sa gugma,” I am brought back to packed Sunday masses and Sinulog processions wherein the crowd sways their hands in unison and sings as one to honor Christ, the Child-King. This is the only time you see the titas and doñas of Cebu alongside the city’s prostitutes, thugs, and downtown drag queens. I share this memory with countless Cebuanos and devotees of the Sto. Niño across the world, and I’m drawing from this well of images, sounds, and emotions when I present these words in the novel, describing the mythical first singing of this song:

The gesture transforms the entire gathering. Hundreds of hands wave side-to-side like sea grass moved by gentle tides, bodies swaying in shared rhythm. Even your bilanggô, whose name alone makes children cry and warriors touch their amulets, joins in the motion, his scarred hand waving toward the Child-King’s image.

“Batobalani sa gugma” is the most famous hymn to the Niño and it means “magnet of love.” In the novel, Humabon shares my appreciation for this serendipity of words:

You savor the poetry of her choice – batobalani, the lodestone that draws all things to itself, singing of love’s magnetic power. Its aptness given her name makes you want to laugh with delight, but you hold it inside like a sweet secret between you.

I also feel this joy because none of this was planned! At least, not by me.

It feels divine how pieces of the story also lock into each other like a jigsaw puzzle, and how real-life events form and present those pieces. I found out during the writing of the novel that “divine” and “diwata” share a common Indo-European root. It really felt like the story came from muses and my role was just to simply listen to them.

For instance, Paraluman is a Tagalog in the novel because my writing coach for RVC, the novelist Mitya (R.M.) Topacio-Aplaon, mistakenly sent me this text message meant for his wife when we were about to meet up at Milestone Café in Cagayan de Oro (shared with his permission):

I found this so amusing that I just had to include this as an inside joke in the novel. Humabon’s wife would have to call him “mahal,” so she had to be a Tagalog. It also felt like diwata intervention. This apparent happenstance opened several avenues in the story. It allowed me to naturally allude to the Cebuano language situation, an issue I care deeply about. It also allowed me to make use of scriptural Tagalog to evoke an ancient prophesying voice when Paraluman declares,

At sa takdang panahon, babangon ang isang binukot na magpapakita ng tunay na kulay ng kanyang balat sa harap ng lahat. Hindi siya magtatago sa anino. Yayakapin niya ang liwanag ng araw, at dudurugin niya ang ulo ng ahas. Ang kayumanggi na ina ng kayumanggi na hari ay magdadala ng bagong panahon para sa ating mga anak.

I didn’t have any literary friends prior to writing RVC. Aside from Mitya, Nathan Go, the author of the novel Forgiving Imelda Marcos, was one of the firsts. I remember talking shop with him at Coffee Cat Davao. After pitching the story to him—at this point it was going to be an opener for a non-fiction book about power—he told me that “it sounds like a novel.” He said this like a gold prospector who had just struck the mother lode. Through him, the diwata activated the mimetic desire within me.

Nathan got one of the first copies of RVC, and he rightly sensed that my depiction of the binukot was inspired by the Bene Gesserit in Frank Herbert’s Dune. But I was not only thinking about Lady Jessica as I was writing those Tagalog lines. I was also hearing the terrifying voice of Cate Blanchette’s Galadriel in the film adaptation of Lord of the Rings, when Frodo offers her the ring and she contends with the temptation to absolute power. Here are the words from the book, which are richer than what she actually says in the film:

And now at last it comes. You will give me the Ring freely! In place of the Dark Lord you will set up a Queen. And I shall not be dark, but beautiful and terrible as the Morning and the Night! Fair as the Sea and the Sun and the Snow upon the Mountain! Dreadful as the Storm and the Lightning! Stronger than the foundations of the earth. All shall love me and despair!

Yet Paraluman did not originate from Lady Jessica or Galadriel. These expressions of feminine power were simply what I had in my literary palette. Her source was real life. The Filipino historical novels I’ve read seem to use the past to deliver “moral lessons” for the present. I wanted to do the opposite. I wanted to use the present to fill the gaps of the historical and anthropological record, like the way modern DNA is used to complete dinosaur genomes in Jurassic Park. Pigafetta recorded 160 Cebuano words in 1521, and surprisingly I could understand most of them! If there’s any truth to the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis—that language is an expression and frame of culture—then I share much of the cultural DNA of Humabon and Lapulapu.

I was in the middle of my masters in Anthropology as I was writing RVC, specializing in the figure of the orang besar—the Southeast Asian Big Man. So I knew the state of scholarship on the role of women in the ancient and present Austronesian power structure centered on the charismatic and violent man surrounded by a mandala of kin, dependents, and allies: practically zero.

What academia lacked in written knowledge, I felt had in my cultural DNA. After all, I grew up surrounded by all sorts of powerful women. I wouldn’t call myself a feminist: I’ve never been involved in promoting women’s rights or whatever the political project of feminism is. And I grew up steeped in some of the strongest strains of Filipino machismo. Yet, Gabi Francisco, editor of Ex Libris Philippines, told me that RVC is “very feminist.” She was the first to write a full book review of the novel, and she told me this in our conversation at Auro Café during the Manila International Book Fair four months after the release of RVC.

This is the power of what I call “neo-animism.” I first learned about this approach from Liz Gilbert, in her book Big Magic. To her, ideas are living beings from somewhere beyond this world. Their life-defining desire is to be made manifest in our world. This could only happen through the creative work of humans. So they roam the earth looking for partners. When they find one, they reveal themselves. This is the experience of inspiration. I was brought up as a hard science supremacist, so this language was not natural to me. But this is exactly how it feels when a creative possibility—like a novel—appears in your mind!

As I read up to recreate the culture and psychology of Humabon and Magellan, I found out that both came from worlds still enchanted and filled with life. As one episode of The Emerald podcast is titled, “Animism is Normative Consciousness.” The modern Western mind is the exception, not the norm. For instance, the Catholicism of Magellan’s sailors was very much animist. Here’s how Pigafetta records their thanksgiving after surviving a storm somewhere in Mindanao, six months after the death of their captain:

One Saturday night, 26 October, while coasting by Birahan Batolach, we were assaulted by a furious storm; thereupon, praying to God, we lowered all the sails. Immediately our three saints appeared to us and chased away all the darkness. St Elmo remained for more than two hours on the maintop, like a torch; St Nicholas on the mizzentop; and St Clara on the foretop. We promised a slave to St Elmo, St Nicholas, and St Clara; we gave alms to each of them.

Like the average Westernized Filipino, I initially assumed that these were mere symbolism. However, when I put myself in the shoes of the devotees of the Santo Niño, I can see again with eyes unclouded by the bare rationalism of modernity. To quote Julius Bautista in his paper “On the Personhood of Sacred Objects: Agency, Materiality and Popular Devotion in the Roman Catholic Philippines,”

In recent decades, anthropologists have critiqued what is perceived to be an antiquated and somewhat simplistic notion of animism as “an idea of pervading life and will in nature” (Tylor 1871, p. 260). Religious studies scholar Graham Harvey has been at the forefront of the effort to renew the concept by focusing less on spiritual animation in favor of an emphasis on a relational personhood that extends beyond human beings. Harvey defines ‘animists’ as “people who recognize that the world is full of persons, only some of whom are human, and that life is always lived in relationship with others” (Harvey 2006, p. xi).

As I embraced this neo-animism in my work, I not only accepted the agency of the muses behind stories; I also recognized the agency of characters within them, like that of Paraluman telling me that RVC is as much her story as it is Humabon’s and Magellan’s.

I use “the diwata,” by the way, as a collective, similar to LOTR’s “the Rohirrim.” The diwata of creative work—the muses of the ancient Greeks—do not only speak to our hearts and minds; as Liz Gilbert relays in her own life, they also work through the people around us. Mitya’s missent text message is just one example. Another writer, John Bengan, was their medium for some writing lessons and for countering my attempts at escaping my calling.

I got to know John through Nathan and we hung out a number of times at Habi at Kape Davao. In one of our conversations, I told John how impressed I was with his range of literary voices in Armor, his collection of short stories. He explained that he practiced a kind of “method acting” in writing them. I eventually adopted this approach in creating RVC. Everyday, during my writing sessions, I would enter the minds of my characters and live within the world of the novel. This made the story an adventure instead of an execution of some rigid blueprint. Although the plot was constrained by history and anthropology, the characters had a lot of agency within these borders. My principle was: extreme scholarly faithfulness to what is written and extreme creative wildness in what is not.

Over more than a decade, the diwata of the novel gradually revealed their proposal. John was one of their final messengers. I initially had this self-image of an essayist and an explainer, not an artist or a storyteller, but John helped change my mind. When I casually mentioned to him how I grew up in Pari-an, the area in Cebu that Humabon once ruled and where the events of the novel took place, John reacted as if this was a sign of my calling. I also told him about my plan to look for a comic book artist to help me turn the story idea into reality. He looked disappointed, like I was shirking some kind of responsibility. Okay, okay—I eventually told the diwata—I’ll f**king do it!

As a scholar of culture, I also use neo-animism to see and work with the large cultural forces that haunt and color the lenses with which we see the world. In my daily work of manifesting the novel, I had to protect the story from some of these spirits and let others in, like an exorcist or a shaman. One of these spirits I let in was the force behind Paraluman—the spirit of hidden feminine power. I’m so grateful that this spirit entered the story because, like salt on a dish or a contrasting color on a painting, this feminine power turned what would have been a dry and arid political chess game between two sociopaths into a much richer, nuanced, and truer story.

I sense that the Humabon who both charmed Magellan and massacred his men is inaccessible to most writers because they are possessed by post-Holocaust morality or the epistemology of the postcolonial nation-state. Part of me remained immune to these—the part shaped before such worldviews existed. To find more potent and more ancient strains of Filipino machismo, one would have to look to Tondo or Bangsamoro. Neo-animism and literary method acting allowed me to fully embody and express this part of me—as well as to transcend it—so much so that Gabi read RVC as a feminist novel. In a sense, she is right. The story’s metafictional author, Doc Camy, has an unmistakable feminist perspective, as can be seen in her afterword:

We also hope this translation offers Western readers a glimpse into how history looks when viewed not from the deck of a Spanish galleon but from behind the woven walls of a payag, where women who never appeared in colonial chronicles nevertheless shaped the course of events through their influence on powerful men and their own direct wielding of power.

In one of the book events for RVC, a reader asked me why both the book’s fictional translator and author are women. The cheeky answer is “because that’s what the diwata wanted!” If I put on my rationalist hat, however, it would go something like this:

David Deutsch, in his book The Beginning of Infinity, theorizes that creativity is a kind of mental trial-and-error, similar to the scientific method, but whose empirical basis is beauty instead of correspondence to measurable physical reality. This process seems largely subconscious. There were countless nights when I woke up at around 3AM, excited with a solution to a puzzle in the story’s plot, structure or wording. It was very satisfying, like finding an elegant winning move in some kind of 4D chess. Yet it was also extremely weird. Like, where did I get that certainty of right and wrong moves? The best answer I found is from Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow. What he calls “System 1” thinking—that fast, instinctive mode that chess players and freestyle rappers use to make impossibly correct split-second choices—is very much how it felt to find the perfect jigsaw piece while being in a flowstate that allowed me to feel all its adjacent pieces in a multidimensional space, and sense—with ASMR-like satisfaction—the frictionless slide of precision-machined parts dissolving into seamless whole. Swak! All those years of reading beautiful fiction trained me for those moments.

Choosing Maria Carmen Kintanar-Lozano, PhD, to be the story’s fictional author and her teenage niece, Samantha Gonzales, to be its fictional translator, was swak. I felt it click into place. I must admit, however, that I stole that metafictional move from Miguel Syjuco’s Ilustrado. I told him so when I chanced upon him at the Frankfurt Book Fair. I also recommended a history book when he told me about his next project. Later, he told me that I was a godsend—so perhaps I was also one channel of his next book’s diwata.

I mention Miguel, Gabi, John, Nathan, and Mitya because there are invisible bonds between those of us who read and who write. That includes you, dear reader! Not even death can sever these bonds. It has been more than two decades since I’ve read Nick Joaquin’s The Summer Solstice, itself a Filipino man’s contemplation of ancient feminine power. Yet I am certain that it was through him and through his story that Paraluman entered Rajah Versus Conquistador. In that fateful December morning at—recall the name—Café Prelaya by the Joaquins, Paraluman asked me to introduce her with these lines—lines whose imagery comes from The Summer’s Solstice, including a paragraph that some might consider an act of homage and others plagiarism:

You enter, hands already positioned for a respectful bow. The oil lamps cast dancing shadows on the walls of finely woven nipa. The air is heavy with incense – storax and benzoin, the same perfumes used in the death rituals of datus.

You dare to raise your eyes for a moment and you catch a glimpse of her. Through the haze, you see her seated on an elevated platform, sitting on silk cushions from Johor. She is dressed in the manner of Bruneian nobility – layers of rich fabric completely covering her form, making her seem larger than life. Her lips are stained with deep red from betel nut, while atop her head sits an elaborate headdress made of palm leaves.

“Closer,” she commands, her voice carrying the authority of someone accustomed to being obeyed.

You crawl forward on your hands and knees, your garments dragging against the bamboo floor. She watches your approach with the detached interest of someone observing a ritual they’ve seen performed many times before.

When you reach her feet, you pause, waiting. The moment stretches like honey dripping from a comb. This too is part of the ritual – this moment of anticipation, of power held in perfect balance.

“You may kiss my feet,” she says finally. She raises her skirts and contemptuously thrusts out a naked foot. You lift your dripping face and touch your lips to her toes. You lift your hands and grasp the white binukot foot and kiss it savagely – you kiss the step, the sole, the frail ankle.

And that, dear reader, is how the diwata got me to write a feminist novel, despite being steeped in Filipino machismo.

Bravo, kuya. So much color - I hope its not drug -induced lol. You crowded every inch with shades of Christianity, Cebuano and Tagalog pre-history, even LOTR was mixed in ! Enjoying it completely haha