Things Hidden Since 1521

Diving Into René Girard's Methods and Maps of Reality

Every few years, I get lucky and come across an idea that uncovers things previously hidden in plain sight. The most recent one revealed to me secrets of the nature of desire. I realized that I spent my life getting good at turning my desires into reality—productivity, project management, entrepreneurship—yet I never asked where these desires come from.

The idea came as a surprise through what looked like one more pop psychology book. It was recommended by someone I trust, so I decided to read it. The book was Wanting: The Power of Mimetic Desire in Everyday Life by Luke Burgis. Its main idea is that most of our uniquely human desires are mimetic: we unconsciously copy the desires of people we consider models or rivals.

The revelation of mimetic desire has expanded my freedom. Now that the sources of my desires are more transparent, I have greater power to direct their focus. This has been a kind of purification. For instance, I decided to end an entrepreneurial undertaking I've been working on for years (I publicly broke up with this muse), and I have said No to the shiny new objects of desire in the various tribes I belong to. Shedding these desires allowed me to focus on a few important ones. I've been more at peace, and there's probably a better chance of bringing my projects to life because of this focus.

This idea—mimetic theory—comes from René Girard, a French historian, literary critic, and philosopher. I wanted to know more about his ideas, so I enrolled in this course and started reading his books and scholarly articles. My first question was this: how did Girard discover this truth about human nature?

As of this writing, I have only completed one of his books, The Scapegoat. The book answered my main question and added a few others. However, those answers made me so uneasy that I had to question my own process for filtering models of reality—of what is true.

This post lays out my plan for exploring that uneasiness, Girard's answers to my questions, and how I'll apply what I learned from him to my own scholarship.

Is Girard telling us the truth?

In the first few chapters of The Scapegoat, Girard looks at accounts of persecution and myths and notices patterns in these stories. He uncovers things hidden in these texts, through a sort of literary triangulation.

He argues that these stories indicate hidden persecution and murder of someone or a group of people in a community—to restore peace in that community. Scapegoats were actual people.

The power of this murder to magically restore peace in a community, according to Girard, is the seed of religion. He presents the hidden patterns of myths and rites, and like rewinding the time-lapse of a decomposing carcass, he reconstitutes their common origin.

Here's a video explaining this theory.

My academic background is in engineering and science. This is probably the source of my uneasiness with Girard's methodology. My instincts tell me that he does not conform to my existing filters of what I accept as true.

But what is truth?

Truth is a map to the territory of reality

It turns out that there are multiple definitions of what truth is. My goal is to explore my uneasiness and be open to what Girard has to say, so I'm picking a metaphor to anchor this exploration: truth is a map to the territory of reality. This image fits varied approaches to truth:

Aquinas: the map corresponds to the territory

Popper: the map is made through repeatable and falsifiable measurements

Postmodernism: but who made the map, and what are their biases?

Critical Theories: remake the map for the powerless ✊🏾

These are key vantage points in relation to Girard's approach because:

He clearly believes in his map's correspondence with reality

He claims that it is scientific, though not in the Popperian sense

I sense in his approach an affinity with Postmodernism and Critical Theories

I'm embarking on this journey naively, as someone with no formal training in philosophy and with some old biases against Postmodernism. Joining me in this exploration might be valuable for those with the same background and the same kind of ignorance.

How did Girard create his maps of reality, and do they correspond to the territory?

The most common map-making approach I noticed in The Scapegoat is what can be called Insight Through Blindness. In a future post, I'll present examples of how Girard does this. I sense a similarity with "deconstruction" in Postmodernism. Perhaps they are the same. However, my little exposure to that world tells me that Postmodernism and Critical Theories tend to focus on blindness from power. Girard, in contrast, is indiscriminate in the kinds of blindness he uncovers.

Girard's process reminds me of There Is No Antimemetics Division, a science fiction novel. The book is set in a world where secret government units (our heroes) fight against monsters that destroy people’s knowledge and memory. These powers are a kind of defense mechanism: you can't kill what you don't know or remember. The protagonists in the Antimemetics Division use the gaps in their knowledge and memory as data in their fight against these monsters called "antimemes."

Like the Antimemetics Division, Girard uncovers things hidden precisely through the gaps of information in texts. There is a metaphorical antimemetic monster at work throughout history, with predictable patterns of the collective memory it erases. In The Scapegoat, Girard compares texts from persecution accounts, myths, and sacred scripture from all over the world to uncover these patterns. Armed with these patterns, he uncovers things hidden within these texts, like a memetic archeologist.

Is this a valid way to truth, a reliable method of constructing maps of the territory of reality?

As I read The Scapegoat, it was as if Girard was reading my mind. He anticipated my anxieties with his approach and addressed them. I'll present these in a future post.

(A Short Digression: Countering an Antimeme)

There’s an antimeme at work here right now. Let’s innoculate ourselves from it before we proceed. “Mimetic” and “memetic” look and sound so similar that there is a likely risk of confusion. This visualization helped me distinguish the two: “mimetic like mimes” and “memetics is like genetics but for the spread of ideas.”

The Darwin of the Social Sciences

My most recent formal academic pursuit was in biology (that muse I broke up with came from this world). And Girard is frequently referred to as "the Darwin of the Social Sciences." These led me to start reading The Origin of Species. I'm still at the beginning of the book, but I already see similarities with Girard's writing. Like Darwin, Girard's created a map of uncharted territory. He lays out an undiscovered forest. Zooming in on trees would only slow him down. In Darwin's case, succeeding mapmakers did the work of filling in the details. They corrected some of Darwin's mistakes, but from then on, the scientific community used the map he outlined. The usage of "theory of evolution" in books across time visualizes this paradigm shift. If I read Origin of Species before it became the dominant paradigm, would I have felt the same unease I experienced in my first encounter with Girard’s approach? I’ll write an essay comparing The Scapegoat and The Origin of Species to answer this.

My goal for this future essay is to transport myself and my readers to 1859. The scientific approach we hold sacrosanct today was not around when the maps they were founded on were made. The theory of evolution was later supported by data from rigorous empirical methods, but the sketch of the territory that Darwin provided comes from improvisational pattern matching, similar to what Girard does in The Scapegoat. (I'll consciously look for points that disprove this as I read Origin of Species to counteract my confirmation bias).

I'll refer to this article on the evolution of scientific writing style by Roger’s Bacon in that future essay. Establishing that the current standard format (Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion or IMRAD) is an artifact of the present-day scientific community would be a good starting point in this attempt at time travel. Here’s a section from that article:

In The Scapegoat, Girard claims that his approach is scientific but not in a Popperian sense. What does he mean by this? I'll attempt to answer this in the same essay.

Reusing Girard's Methods and Models

To better understand Girard's maps of reality and his approach to their creation, I'll reuse them for my own writing and scholarly work. First, I will be doing that with the essays I promise above. I'm seeking insights by uncovering the blindness that stems from my academic and professional training.

The approach I propose above also reuses something I learned from The Scapegoat. We can call it Epistemic Fairness. It is more rhetorical than methodological. In the first chapter, Girard presents text from Guillaume de Machaut, a 14th-century French poet and composer. History tells us that Jews were persecuted and killed during this time. Girard uses this knowledge to uncover the violence and murder hidden in the text from de Machaut. The approach is straightforward and commonsensical. Girard later uses our agreement with this logic to counter our instinctive resistance in applying the same method to other texts, like a jiu-jitsu move against an antimemetic monster. If we can create a map of A using method X, why would we not create a map of B using the same? This is partly why I'm comparing Girard with Darwin.

In The Righteous Mind, Jonathan Haidt presents how WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic) individuals tend to hold only two sacred values: avoidance of harm and fairness. He contrasts with the rest of the world, which holds these two along with three other values: sacredness, respect for authority, and loyalty to an ingroup. Girard must have intuited this from his WEIRD readers, thus the repeated usage of Epistemic Fairness.

The Strange Intersection I'm Positioned to Explore

In The Scapegoat, Girard points out the limitations of the perspectives of the texts he analyzes. He also encourages us to use our intuition as data, conscious of its strengths and biases. This is why I am leaning into instead of ignoring my uneasiness with his map-making approach.

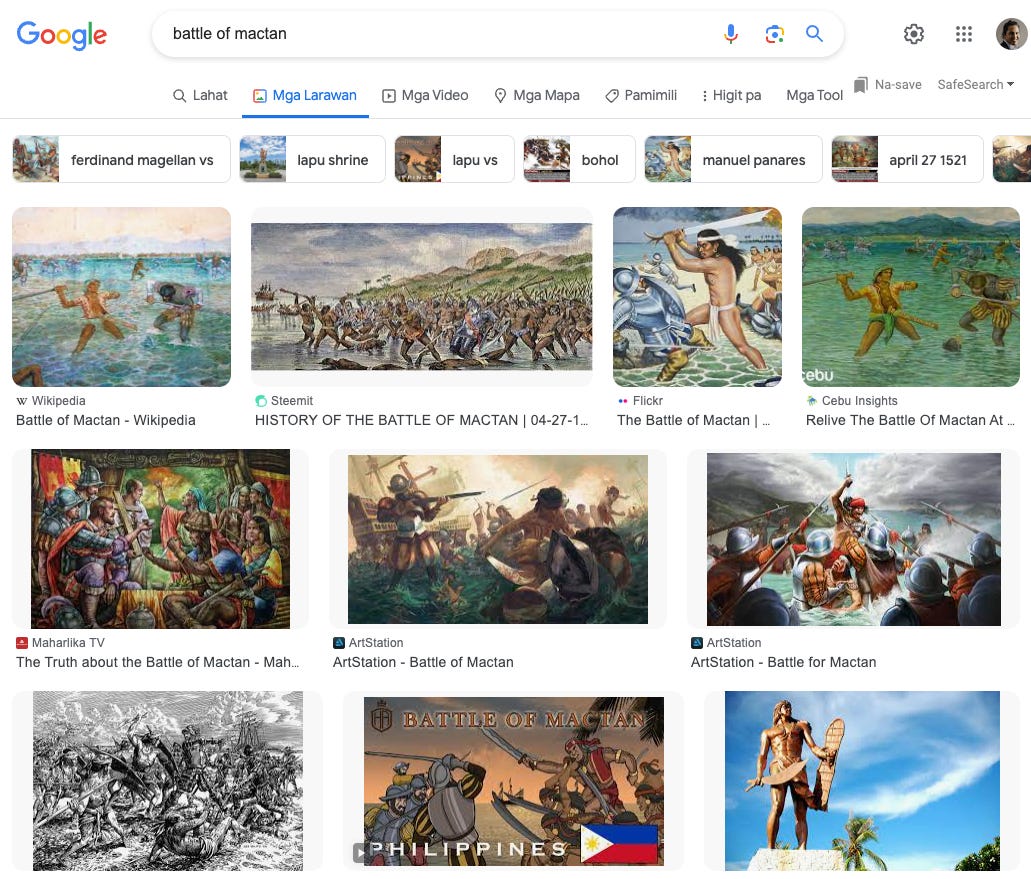

My choice of text to apply his approach and models also stems from leaning into an intuition. The city I grew up in recently celebrated 500 years since 1521. 500 years of what? It depends on who you ask. To Filipino Catholics, it is the 500th anniversary of Christianity in the islands. To Filipino Nationalists, it is a commemoration of the "Victory at Mactan," the first battle in the long struggle against colonialists. To the global publishing industry, it was the 500th anniversary of the 16th century's equivalent to the Mission to Mars: the first circumnavigation of the world by the crew led by Ferdinand Magellan.

The primary text on which all these perspectives are based is Antonio Pigaffeta's Account of the First Circumnavigation of the Earth. Pigaffeta was a well-educated nobleman from the Republic of Venice who negotiated a place for himself in Magellan's voyage. He did this because he wanted to become a famous writer. He got the adventure he wanted, including close encounters with alien civilizations and with death. His account of the voyage made him famous. Other texts from fellow crew members corroborate his accounts, but they are mostly seamen's logs and statements from legal proceedings.

I will apply Girard's methods and models to the section in Pigaffeta's account that relays the last days and the death of Ferdinand Magellan. I'll then apply the same methods and models to subsequent retellings of the same event. I sense that there will be interesting things hidden since the 16th century that we will uncover through insights from blindness.

For instance, the most interesting blindness in Pigafetta's text, from a Girardian point of view, can be seen in the interaction between Magellan and the local ruler that allied with him, Rajah Humabon.

The greatest exposed blindness that underpins Girard's work is our current tendency to side with victims over persecutors. Girard says that this tendency comes from the message of the Jews, especially Jesus of Nazareth, which has since spread throughout time and space. Wouldn't the interaction between an "unadulterated" pagan power player and a Christian conquistador be supremely interesting?

I have been hearing this story of this encounter since I was a kid. I grew up in the area ruled by Humabon, and there is a statue of him two blocks from my childhood home. However, I only read the primary source around eight years ago. At first, Humabon seemed like a cartoon character. Then one day, I imagined him to be a local politician. Suddenly, his actions made so much sense. He became a man of flesh and blood.

It turns out I have an archetype in my head that fits Humabon's actions perfectly. This archetype comes from knowing local leaders and power players, from the teenage kingpins in the city of my youth to CEOs of giant companies to murderous politicians. My experience working with Western-style leaders in multinational corporations has made the Humabon archetype even more distinct.

The best academic articulation of this archetype I've encountered is the book An Anarchy of Families, a collection of scholarly essays on Philippine political families edited by Alfred W. McCoy. Several references in the book point toward the "Big Man," an anthropological model that describes political leadership in Southeast Asian societies. I'll read up on this and then write an essay. This will also be a good time to read Sun Tzu's Art of War (circa 500 B.C.), as China was already dominant and influential in Asia by then (we hear about it from Pigaffeta). Here's the Girardian angle: Art of War is a playbook that should be "uncontaminated" by the Judeo-Christian preference for the victim.

Magellan also sounded like a cartoon character, especially with the utter tactical stupidity that led to his death. The book Over the Edge of the World by Laurence Bergreen subtitled Magellan's Terrifying Circumnavigation of the Globe, changed the Magellan in my head from a two-dimensional caricature of Don Quixote to a human being with a complex personality that evolved throughout the voyage. He clearly had a religious conversion. I'll look for studies on the anthropology and psychology of conquistadors to balance the study of Magellan with Humabon.

I plan to use A.I.-generated images to create comic books based on each of the prevailing perspectives (Postcolonial Nationalist, Catholic, and action-adventure story) and then create another one based on what we can uncover with the Big Man and Conquistador essays. Girard's scapegoat mechanism will flesh out the story further. I'll show how Humabon's actions make a lot of tactical sense, displaying probabilistic and no-lose decision-making. I'll show how he systematically tested Magellan's strengths and weaknesses. Failing to find in Magellan the usual weaknesses of men, Humabon used the conquistador's virtues instead as the instrument of his defeat: Magellan's courage, loyalty, honor, friendship, and—here's the Girardian angle—his Christianity. Using Chapter 11 of The Scapegoat, The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist, I'll show how Magellan fits so well as a scapegoat. Humabon's tears for Magellan's death and the subsequent massacre of Magellan's crew by Humabon's men also make much more sense from the Big Man and Girardian lenses, compared to the usual Nationalist explanations or its utter silence.

This comparison of a pagan Big Man and a Christian conquistador might be a way to make one of Girard's key claims falsifiable. If the preferential option for the downtrodden is uniquely Judeo-Christian, then we should not find it in the playbook of Big Man and in the actions of Humabon. This is another similarity with Darwin. It has been 164 years since the publication of The Origin of Species. Just one ex niliho creation of a new species would have falsified the theory of evolution. Yet all the data we have gathered support it: Mendelian genetics, observation of fast reproducing organisms like bacteria, DNA, and vestigial organs.

Postcolonial Nationalists, Psychopaths, and Nietzsche

I sense that nationalist myth-making is a rich area for Girardian uncovering. With just a bit of browsing in Philippine history books, I quickly saw two tendencies of myth makers that Girard points out in The Scapegoat:

Stacking crimes on the scapegoat (e.g., Oedipus's incest and parricide): one book claims that the crew that was massacred after Magellan's death raped some local women

The collective murder is transformed into one person's homicide: the Nationalist depictions of the death of Magellan are never by a mob but by the hero, Lapu-Lapu (who, by the way, is never seen first-hand by our primary sources):

Here is how I will explore Philippine Nationalist scholarship with a Girardian lens:

I'll make a table showing which parts of the primary source are hidden by books that relay this episode. Then a bit of reading on Philippine Nationalist Historiography (this paper from Mojares and this speech from Illeto look interesting). Another essay might emerge from this work.

I'll revisit Benedict Anderson's Imagined Communities. I read this book in my early twenties, and it is my first memory of the awe of suddenly seeing things hidden in plain sight. It unveiled the map of reality I was reared with.

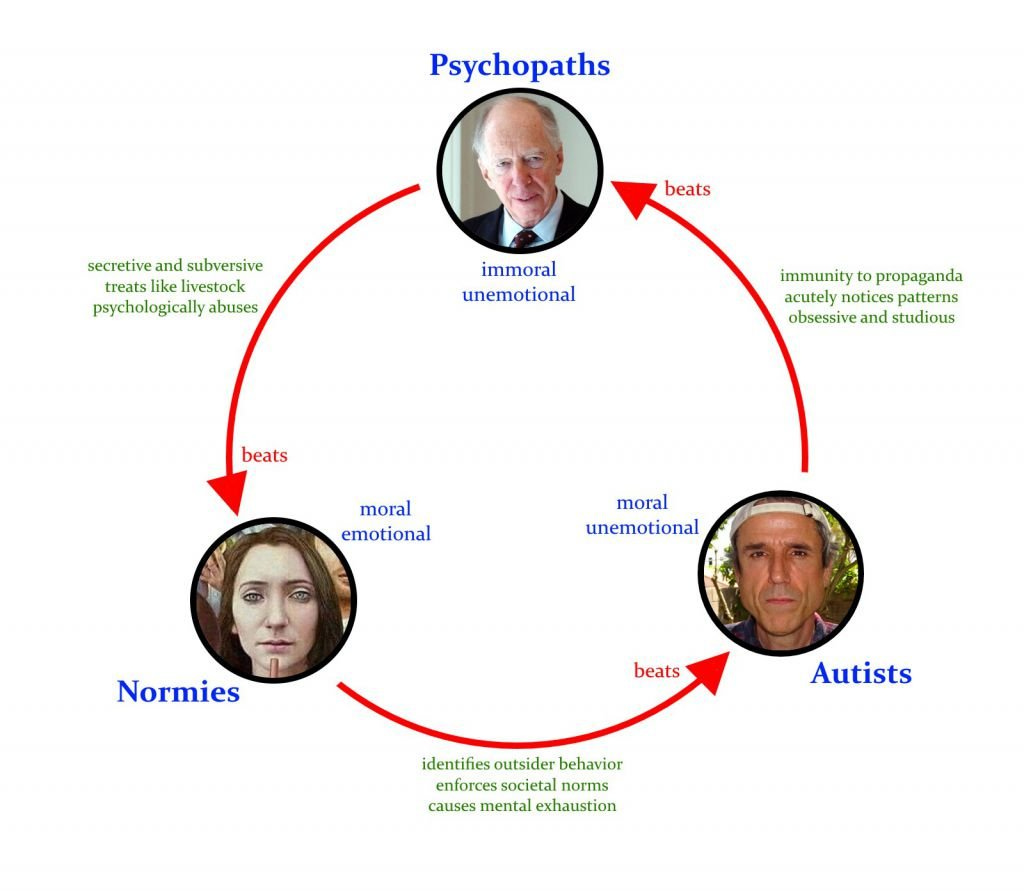

I'll explore Philippine Nationalist scholarship from lens of Venkatesh Rao’s The Gervais Principle. Here is a diagram from Rival Voices's The Glossary, which might be based on those essays from Rao. I sense that this map will uncover things hidden in the dynamics between Big Men, Nationalist scholars, and the general populace.

Girard's Dionysus Versus the Crucified was the most interesting article I read during the Girard course. I'll read Duane Armitage's Philosophy's Violent Sacred: Heidegger and Nietzsche through Mimetic Theory to go deeper into this. Like Girard, Nietzsche uncovered the West's choice of siding with the victim, the weak. Unlike Girard, Nietzsche rejects this choice. To him, siding with the strong is the “life-affirming” choice.

Nietzsche's Übermensch sounds a lot like the Big Man, especially the modern incarnations of this archetype of Southeast Asian political leadership. The Filipino strongmen presented in An Anarchy of Families look like power players that operate beyond good and evil, or at least beyond the good and evil as defined by Liberal Democracy. Across the monographs that make up the book, Ferdinand Marcos appears as the biggest Big Man. In The Spectre of Comparisons (how Girardian is that?), Benedict Anderson calls him the supreme cacique. Can we use Girard’s approach with Marcos’s writing and uncover his moral underpinnings?

I'll also read some of Ninoy Aquino's writing. I sense an interesting parallel between these two political rivals and Humabon versus Magellan. Aquino seems to have had a conversion in prison, and whoever killed him, Ninoy, without a doubt, willingly walked into his death.

The election of Ferdinand Marcos’s son to the presidency perplexed me and many of my friends and family. Marcos was the villain in our world. Why did our countrymen choose the dictator’s son? I spent a month trying to answer this question, and this essay was the result. To make sense of the people’s choice, I used the concept of “egregores,” which are essentially memetic monsters, to express the clash of worldviews across recent Philippine history. I sense that Girard and Nietzsche can help us unmask more memetic monsters (with antimemetic powers) operating in Philippine history and culture.

I sense that Girard might have a better alternative to the tendency to demonize modern incarnations of Humabon, especially Marcos. I feel an inner red alert just by writing that sentence, reared as I was by the egregore of the EDSA Revolution. I will lean into this inner turmoil instead of avoiding it because I sense a better map of reality on the other side of this conflict.

The fundamental option for the powerful or the weak might also be a good way to contrast 19th- to 20th-century European Nationalism with Postcolonial Nationalism. Nietzsche famously influenced the Nazis, while modern Filipino nationalists appear to have a preferential option for the downtrodden. How influential are Postmodernism and Critical Theories in this fundamental choice? Girard considers these movements that seek justice for the weak to be descendants of Christianity (Bartolomé de las Casas, "the founder of human rights," interestingly was in one of Magellan's fundraising pitches). Unlike Christianity, however, their persecutors are not forgiven but instead demonized, similar to my tendency towards Marcos: satan casting out satan.

I must admit that the writing project I laid out in this post is an excuse to revisit and engage with my favorite authors and thinkers. I’m particularly looking forward to rereading the books of Resil Mojares, or reading his books in my antililbrary. I browsed one entitled Brains of the Nation as I was finishing this post, and I came across this paragraph (emphases mine):

THE NATIVE ENCOUNTER with European knowledge did not begin with Pedro Paterno, T.H. Pardo de Tavera, or Isabelo de los Reyes. When in 1521 Ferdinand Magellan plied chief Humabon with gifts, thrilled him with words extolling the power of the Spanish King and God, and proceeded to convert him and his followers, thought worlds collided. Humabon did not have a Pigaffeta to record the native side of the encounter. The events that followed however—Magellan’s death in the shallows of Mactan, the massacre of his men—illustrated what has been demonstrated time and again: acts of conquest and conversion are not always what they seem.

Where This Is Going

I'm also embarking on this 18-24 month (?) writing project to search for my next book. I'm still interested in a comparison between the Philippines and Mexico. This current exploration through Girard's methods and models lays some of the foundations of the Philippine side of the comparison.

My last book, How to Turn Ideas Into Reality, is a playbook for creative endeavors such as this. I'll again work with the garage open and within creative scenes. The scenes were mostly in Twitter for the previous book. What are the right scenes for this one? IndieThinkers.org, organized by the same people behind the Girard course from which this essay emerged, seems to be one. Perhaps Luke Burgis’s community as well. Another might be the community surrounding The Seeds of Science. One of its founders wrote the study on the evolution of scientific writing styles above. A few scholarly essays that fit that and perhaps other more traditional publications might emerge from this exploration. Lastly, I need to test these ideas and their delivery with normie Filipinos as early as possible. This probably means creating videos for YouTube and Facebook from the essays I'll write.

In two to four years, I hope to complete my next book. My goal is to have it published by a local publisher and collaborate with a scholar I look up to. I hope to create another diagram like this one by then. I invite you to take part in this journey by subscribing to this newsletter and start having a conversation.

If you're looking further into the ideas of the Anarchy of Families, you may wish to look into Dante Simbulan's Modern Principalia. He looks into who became a principalia, and why, tracing them back to colonial times. Professions and ideas included.

The reference I have for Philippine History is O.D. Corpuz's The Roots of the Filipino Nation - which I prefer to the Agoncillio textbook both for its completeness and focus on some things that one may not expect from a colonization. As an example, the failed integration of the Filipinos into the Spanish system due to colonists hopping the ship at Acapulco and never making it, reducing the check on the power of religious organizations.

One of the sections that stuck with me described the constant push and pull of early colonization - friars and Spaniards would go out and bring the pre-Filipinos into the pueblos to proselytize to them. Because there were too few Spanish to truly guard all the outlying pueblos, the people often melted away back into the countryside, where the priests would have to follow them into barrios and establish churches there. This to show that the early colonization was far less orderly and uniform than one may think - and harken forward to the extreme gap in barrios and cities in the modern Philippines.

You could almost say that the Phlippines ended Spanish colonization as two separate countries - the cities and the countryside, the modern and the ancient - something you touched on in your piece on BBM/Leni and the battle between the Ancient Egregore and the EDSA Egregore.

The Philippian history project sounds very interesting, and ha, your last diagram is awesome! You must have had fun putting that together. Re: truth... if it's helpful, here's my short take on Girardian truth. https://open.substack.com/pub/fosterj/p/girardian-truth?r=yu4kf&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web