A Conversation on the Making of Rajah Versus Conquistador

Gabi Francisco and Kahlil Corazo on Intuition, Serendipity, and the Strange Journey of Making a First Novel

Gabi Francisco of Ex Libris Philippines and I recorded a conversation during the 2025 Manila International Book Fair. Below is the transcript, edited and condensed for clarity.

Kahlil: So you were saying that Ex Libris started as a college book club in UP?

Gabi: Yes. And then about a year ago, we decided to make a website. Although we’ve been meeting as a book club ever since—17 years! Imagine, 17 years of friends meeting every month, talking about books. And then life happened. Some of us went to Visayas, some to Mindanao. The online meetups became less frequent, and we finally decided to do book reviews. Because there’s no one doing independent, objective book reviews.

If there’s a book reviewer associated with an outfit, it’s usually just press for the book. They’re trying to sell you the book. So we’re just a bunch of idealists. Sometimes we buy the books with our own money. It’s purely out of love for Philippine literature. We’re not earning from this.

And honestly, before your book, we had a wrong impression of indie presses. People had been sending us manuscripts, and sometimes it’s just—sorry, we can’t. You need an editor. Just because you copy-pasted your Facebook thoughts and put it in book form doesn’t mean it deserves to be read.

Then your book came along. When I read it, I couldn’t believe it. Honestly, my expectations were low. And then I was like, oh my gosh, this is like Hilary Mantel, but with action. But make it Filipino. It just blew my mind.

Kahlil: Thank you. I really appreciate that.

Gabi: Just to give you an idea of how much my mind was blown—my day job is I’m an administrator of a school. I handle AP, Araling Panlipunan—Social Sciences. Every year, the veteran teachers mentor the younger teachers. Did you know that your book is in my slide deck?

Kahlil: Oh, wow.

Gabi: It is. The idea was: don’t teach what happened, teach why. I didn’t tell the whole story, but I put the book there and told the teachers the effect it had on me. This is the power of a good book. This is the power of a good teacher. Because like me, I thought I knew history. Then I read your book. Oh, it just makes sense. But in a very accessible way.

People get put off when they hear “literary fiction,” but I mean that as a compliment. It’s not just action. Yours goes into the thoughts of all the characters.

Kahlil: When you wrote that review, it was like, okay, finally. You feel a sense of relief. It actually works. Because you bet years of your life on this thing.

Gabi: Five years?

Kahlil: Well, the first spark was maybe around a decade ago. After I read Pigafetta, I was like, there’s something missing here.

Gabi: So that was your inspiration! That’s one of my questions. What inspired you to write the book?

Kahlil: It was a slow burn. I read Pigafetta around a decade ago. And before that, a few years earlier, I read this book called The Anarchy of Families—a compilation of academic studies and ethnographies of Filipino political families. A particular figure there is what they call the “big man.” That’s a figure being studied in Southeast Asian sociology.1

Gabi: You mentioned this in your other book. I read them.

Kahlil: One day, I just realized that Humabon is actually this guy. I know this guy. Growing up as a Filipino, as someone from Cebu, you are surrounded by this big man. We have a local name, dagkong tao. In the Mindanawan scholarship, it’s Orang Besar, which is just “big man” in Bahasa. Once I saw that, his moves suddenly made sense. The why just suddenly made sense.

Pigafetta just wrote what. He did not see how the big man thought. But once I saw that, I wanted to see the story. For years, I was just telling people, it would be interesting if you approach it this way. And I realized at some point, no one’s going to write this unless I write this. And then I thought, I’m probably the right guy to write this.I spent some years studying anthropology. I enrolled in a master’s in anthropology.

Gabi: It comes out in your footnotes.

Kahlil: I wanted to experience that world. My approach was like method acting. Every day, I would enter the mind of Humabon or Magellan. I’m glad I didn’t go insane that one year LOL. But it was just a weird experience—to put myself into the mind of a 16th century datu.

Through anthropology, I knew the culture. I knew what the role of the big man was. I also went into a study of psychopathy. My perspective is that psychopaths—the term was only invented in the 20th century, pathologized and medicalized… but how would people in the past look at someone who’s now called a psychopath?—from the anthropological perspective, it’s just someone who is not constrained by taboo. One thing I learned is that psychopaths don’t feel anxiety. So I don’t know if you noticed, but in no part of the book did Humabon feel anxiety.2 That’s how I tried to recreate that mind.

Gabi: I felt it. I was there. Not every book does that, especially history books. And I like what you did with the footnotes. It’s better to read the hard copy, to be able to flip between the pages more easily. Otherwise you’ll get bogged down. But you had a very light hand. The story flows like watching a movie.

I wanted to ask, why the frame narrative? The female student finding the manuscript? And why is she female?

Kahlil: My decisions were mostly intuitive. It just felt right. So it’s only now that I’m trying to make sense of it.

Remember I was telling you about Liz Gilbert’s approach to writing? I felt like I was just listening to what this book was supposed to be. In Liz Gilbert’s terms, there’s this diwata of this book, and it’s already there. It just wants to be made manifest. My role is to find out what it is.

Gabi: To be the channel.

Kahlil: I had another way of framing it: I thought “this book already exists in the future” when I was writing it. Now it exists. So my role was just to find out what those words are. A lot of writers have this experience. The thing is already there. You’re just there to discover it.

Now I’m trying to rationalize why it made sense. I’m in academia, so there are voices in my head that are always doing some sort of academic critique. I had to prioritize the storytelling. My North Star is the story. But there are all these other voices with their own agendas. The academic voice had concerns about positionality. It’s a very violent and male-dominated society. And there’s this feminist voice in my head—I’m just surrounded by them.

So I think rather than being defensive about that, I gave a voice to it. I let that voice be present in the book as Doc Camy.

Gabi: That sounds like it makes sense. I actually like that you were honest enough to say that it came by intuition. Some authors plan it out—oh, the trend now is LGBTQIA, so let’s have the token character. It comes out as manipulative. Yours didn’t come off as that. However, my other friend who read it was confused—did Kahlil really write it? Or did he discover it? I’m like, who cares? It’s a great story.

Congratulations, by the way, on going to Frankfurt. I was curious—if the book does get translated, what do you think a foreign reader would get out of it? Because I actually think that a Manileña like me would read the book very differently from my friends in Cebu and Mindanao.

Kahlil: I have no idea. It’s like—

Gabi: Or what do you hope?

Kahlil: Right now, I feel my job didn’t end with the writing. Since I felt called to write it, I also feel called to nurture it. To bring it to people. I’m using all my experience in marketing and sales and business for this book.

Each reader will experience the book differently. I’m just happy that some aspects of the book resonate with some readers—it’s almost like a miracle. There’s a vision in my head. I translate it into words. The words are read by someone. Those words create a vision inside their head. And then they tell me it’s similar to what I had in my head. That’s a pretty insane thing.

I’m just happy if there’s some aspect of the work which transcends that boundary between people. I never really thought about it, because I couldn’t control it. There’s no point in thinking about it or worrying about it.

But you’re right—this is my homage to Cebu.

Gabi: It comes out. You know how when a book is formulaic? Yours wasn’t. You’re waxing poetic over the sunset, the smells, the bells pealing into the future. I thought it was very lovely

We always ask this—who is the ideal reader? The reader over your shoulder? Or do you even have one?

Kahlil: I was writing it for specific people in Cebu. I had them in mind when I was writing it. Also, maybe some scholars. A collection of scholars in a certain domain. I realized I was responding to what they might say. I just accepted it. These are the voices in my head. These are my imagined readers.

But there were also voices to which I had to say—I’m not going to talk to you. This is not for you.

Gabi: Yeah, I saw that in the preface.

Kahlil: Because otherwise it would twist the story. It would go against the story. If I listened to them, I would do a disservice to the story. Some voices were threats. While others—you mentioned the feminist thing. I’m not a feminist. I’m not an anti-feminist. It’s just outside what I care about. Similar to the Moro situation. I know about it, but I don’t have a dog in the fight.

But the story wanted it. So I said, okay, let me put it there. And I think it made the story better.

I got a writing coach—this is my first time to write a work of fiction.

Gabi: It’s your first? It’s so good.

Kahlil: Thank you. I wanted to do this well. And when Paraluman came out, my writing coach said this will make the story better. We met in Baguio, very serendipitously. His name is Mitya. He’s a published author, multi-awarded. We actually have a similar style and novelistic worlds.3

So many things like this happened. Serendipities which led to this book being created. Which is what Liz Gilbert talked about in her book. Not only the inner inspiration, but what’s happening in the world around you. It’s as if the world wants you to create this thing.

Gabi: I wanted to ask also—the genre is literary fiction. Generally, from what I hear conversing with other book people, literary fiction is not the genre you go into if you want to sell. It’s not that sexy. Some people avoid it. They mistakenly feel like they’re not smart enough for literary fiction. But I think it’s for everyone.

Kahlil: I think there are four types of writers in a novelist. One is the storyteller. The second is the wordsmith. The third is maybe the scholar-teacher. And the fourth is the propagandist. In my experience, those were the different kinds of writers battling inside me. It’s a zero-sum game. You couldn’t be a propagandist at the same time you’re a storyteller. I had to fight against making it propaganda for it to be a good story.

Also, I know my limitations. My strength isn’t the wordsmithing. In the literary fiction sense here in the Philippines, what I notice is there’s a lot of experimentation, transgressing the boundaries of words and sentences and paragraphs.

I appreciate technical mastery when I see it. But that’s not enjoyable to me. That’s why I’m hesitant to call this literary fiction. I don’t feel it follows the genre here.

Gabi: For you, what genre would you describe your book as?

Kahlil: The voice I wanted was my memory of this book called Red Harvest by Dashiell Hammett. Very straightforward. Hemingway but grittier. I didn’t actually read it again. I wanted to use my memory of the voice of that book.

And also, I wanted it to be like a translation of Cebuano written in the 16th century. I couldn’t use words like “machine,” “transparent”, “engineer.” My goal was to immerse my reader there, so it has to be words that would make sense in that world. Words that existed in that time.

Gabi: I did not know this. That must have been so hard. You had a working list?

Kahlil: It’s just editing. I also had a conscious bias for Anglo-Saxon words versus Latin words. Latin sounds more like Tagalog and Anglo-Saxon sounds more like Binisaya. Latin-derived words are long and compound—like pag-ibig and kapangyarihan. Pag-ibig literally means “the act of desiring” and kapangyarihan means “the ability to make things happen.” Anglo-Saxon words are shorter: “dog,” “love.” Cebuano words are like that. Love is gugma. Power is gahum.

I felt that would be more representative of Cebuano. And also, when I use metaphors, it had to be things around Cebu. The sun, the wind, the stars, poetry, fighting, spiders—things I experienced as a Cebuano, which I know 16th century Cebuanos also experienced.

I don’t know if that had the intended effect. But that was how the sausage was made.

Gabi: The effect was total immersion in that world. Would you say you had a genre in mind when you started writing, or you just wrote it? Genre be damned, I have a story.

Kahlil: I’m not very familiar with genres. Again, it goes back to this neo-animist approach—there’s this entity that wants to be made manifest. I know what it sounds like. What it is. The writing is a lot of revising: “This doesn’t sound right. I have to do it again. Until—this one, this is it.” The weird thing is I knew that this was it.

Actually, my next book might actually be about that journey. It was such a weird and magical experience that I feel I have to write about it. It also transformed me. That might be my next book. About neo-animism but using the experience of writing this book to talk about it.

Gabi: I feel like the genre question will come up eventually when you market your book. Because as a reader, genre plays a lot. There are readers who identify as literary fiction readers.

That’s why I was nervous that I didn’t know you didn’t think of your novel as literary fiction. For me, when I call a book literary fiction, that’s a compliment. It means it’s not just a one-day adventure. The wordsmithing—you keep saying the wordsmithing isn’t there. I beg to disagree. There are parts I underlined.

Kahlil: Just to add to that—maybe the literary fiction label is appropriate the way I use layers of fiction. That’s common in more modern literary fiction. A fictional writer of the thing you’re reading. I had a fictional translator of the fictional work. That’s more common in literary fiction. Like Ilustrado—those very meta layers.

The people I talked to who are writers in literary fiction understood what I was trying to do. So maybe in that sense it’s like that. But in terms of fitting it in a genre for it to be marketable, I don’t think that’s my job.

But I’m now considering approaching several publishers because I realized how difficult distribution is. I’m okay with the marketing. I have a marketing background. I can do those things. Even the production is okay. But the distribution is just too much. After this experience, maybe it makes sense to work with a local publisher.

What I’m also going to do is approach Grade 11 literature teachers, because DepEd suggests that teachers use regional literature. This is very regional literature, especially for the Visayas.

I feel like I need to work for it to be read by people. Some writers say they don’t care about it—I’m done with my work. But me, this is part of the job. That is the whole point.

Gabi: As a reader, I’m curious—who’s the reader over your shoulder? There are really some authors who don’t give a damn about the reader. True story, someone high up told me face to face when I asked that question, “What a stupid thing to have an ideal reader.” Everybody was aghast because what’s the whole point? For whom are you writing? Is it your legacy? Is it to tell the story of your home in a beautiful way that makes sense?

The senior high thing—remember my day job is school administrator. Right now, the curriculum is changing. We’re all on tenterhooks. The old senior high curriculum does have that. My sister teaches that. That’s why it feeds into the book club thing because we’re always looking for local writers.

As a teacher, I like that your book is suitable for senior high. There’s a bit of violence but it’s not too much.

I like that you’re breaking the mold. There’s this fresh voice from—honestly, when you see the manuscript, no one’s heard of it. It’s a fantastic book. It shows that you don’t have to… other writers have written about this corrupt system. It becomes not a question of skill anymore, but where did you go to school? Who did you study under?

I feel like your book could have only been written by somebody who was not a slave to the system.

Kahlil: I’m an outsider. I don’t even know what that game is. Before this, I had no writer friends. I only started befriending some writers when I was writing this—I needed help. At least I should know how this thing is done.

I befriended some writers in Davao who were instrumental in convincing me that I should write this. Because I didn’t have that identity of being a novelist. I felt like I’m more of an explainer rather than a storyteller. More of an essayist rather than a novelist. I never wrote works of fiction before that.

So maybe it was an advantage. It allowed me just to listen to this thing, what this vision was, rather than whatever this game is. Because I didn’t know this game existed.

Gabi: Thankfully.

Last question. From a lay reader with limited budget and time—you’re always looking for, why should I read your book? Do you worry about how the book might seem? Do you feel that it is relevant?

Kahlil: For the people I wrote it for, I think it’s very relevant. I don’t think anyone has attempted something like that for Cebu. I don’t think anyone has written a book to capture Cebu. I’ve been looking for a book like that. I remember reading Istanbul by Orhan Pamuk. Since I read that, I wished someone would write something like this for Cebu.

The nearest one was the series called The Cebu I Know, Manila I Knew—essays from writers talking about a place. I like that series. But no one really attempted it in a larger sense. I only realized that after I wrote this—okay, this is my attempt at that.

Gabi: But it’s not just about Cebu. At the end, that dynamic between the Binukot and the Babaylan—you expanded it up to 21st century, 20th century Philippine politics. I was like, that makes sense. When I watch plays, local plays, people have written about that dichotomy, how we’re stuck as a society politically. It’s already 2025, how come we’re still stuck? Yours makes sense. No one has written a book like it.

Very grateful to have had the chance to read it.

Kahlil: Thank you so much. I also really appreciate the community’s support for local writers. You write in order to connect. I’m so thankful that your community, many readers’ communities support local writers. Especially as an independent, because one thing a writer wants is to be understood and appreciated.

Gabi: Of course. That’s normal. Affirmation.

Kahlil: The publisher normally does that—you’re accepted, you’re anointed, you did a good job. But without that, as an independent writer, the source really is the community itself.

It feels like a purer relationship. You’re not doing this as your job. I’m not doing this as my job. We simply love books.

Again, thank you so much.

Addendum:

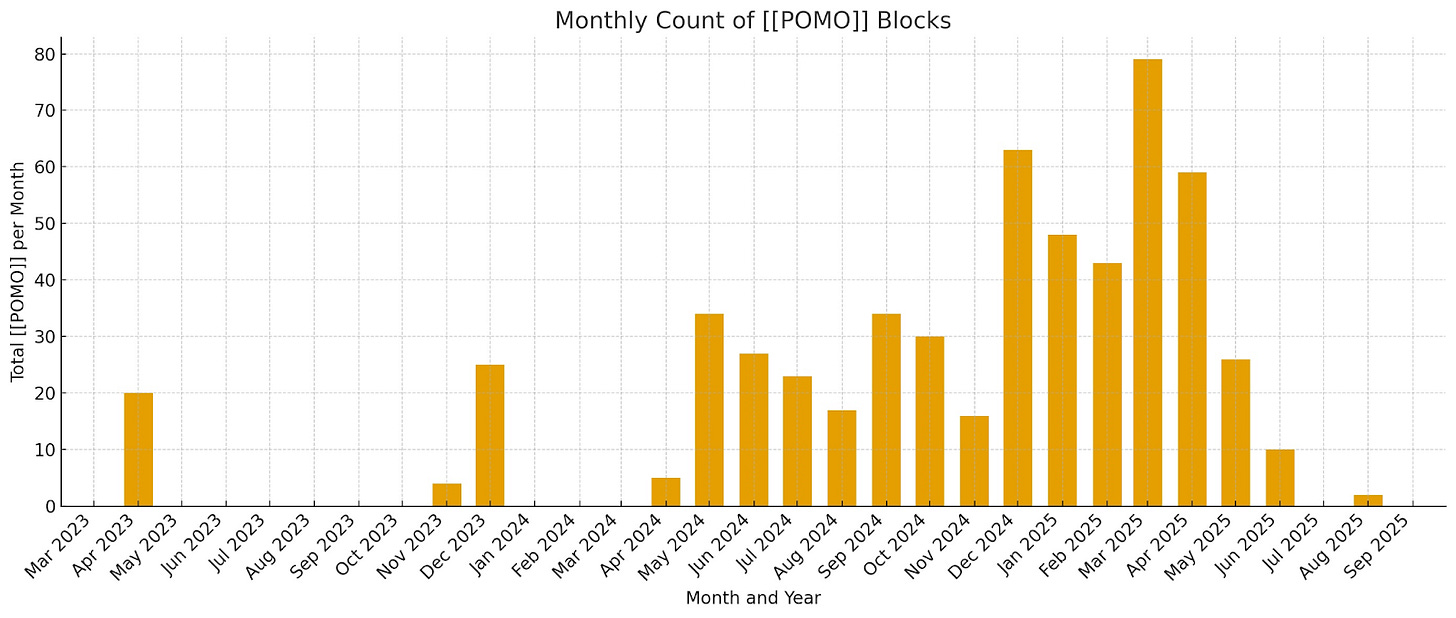

The actual writing took around 300 hours across two years (not counting research). This graph shows the last 15 months of those two years when I treated this novel as my full-time job:

The first few chapters took a month each to write. When I started using the LLM Claude, I reduced that to a few days per chapter. It would have taken me 4-5 years to complete the book had I gone fully manual: https://www.explorations.ph/p/im-writing-a-novel-300-faster-with

Addendum: only in the first part of the novel, before his psychological conversion.

Addendum: in other words, the decision to let the feminine voices enter and perhaps even dominate the story was aesthetic, not political or propagandistic.