Salvation for Flannery O'Connor's Psychopath

I recently had a coffee flight in Toma, one of Madrid's pioneers in specialty coffee. Like flights in similar cafes, they prepared one batch of single-origin coffee into three brews: pour-over, espresso, and latte. Coffee flights allow coffee nerds to get to know and enjoy a bean's flavors thoroughly. This is like speed-dating someone by bringing her to a hike, a museum, and to dinner—all in one day.

I asked ChatGPT what Flannery O'Connor story would pair well with the flight (admit it—you've asked even weirder things from your robot assistant). It suggested A Good Man Is Hard to Find.

Madrid was a side-trip. My main event happened the week before that, a René Girard conference in Rome. In one of the lunches of the conference, my table—which had two Africans, an Irish Jesuit, and an American teacher—ended up talking about Flannery O'Connor. Jonathan, the American, declared that A Good Man Is Hard to Find is the greatest American short story ever written.

Well, I thought, this means I have to read the story—again, probably for the third or fourth time.

I sat in one of the benches at the street outside the cafe, shaded by trees well-maintained by the state. The cobblestone street was amazingly made for people, not for cars. It was a sunny Sunday morning, and around me were young doña moms watching their kids play with plastic kick scooters.

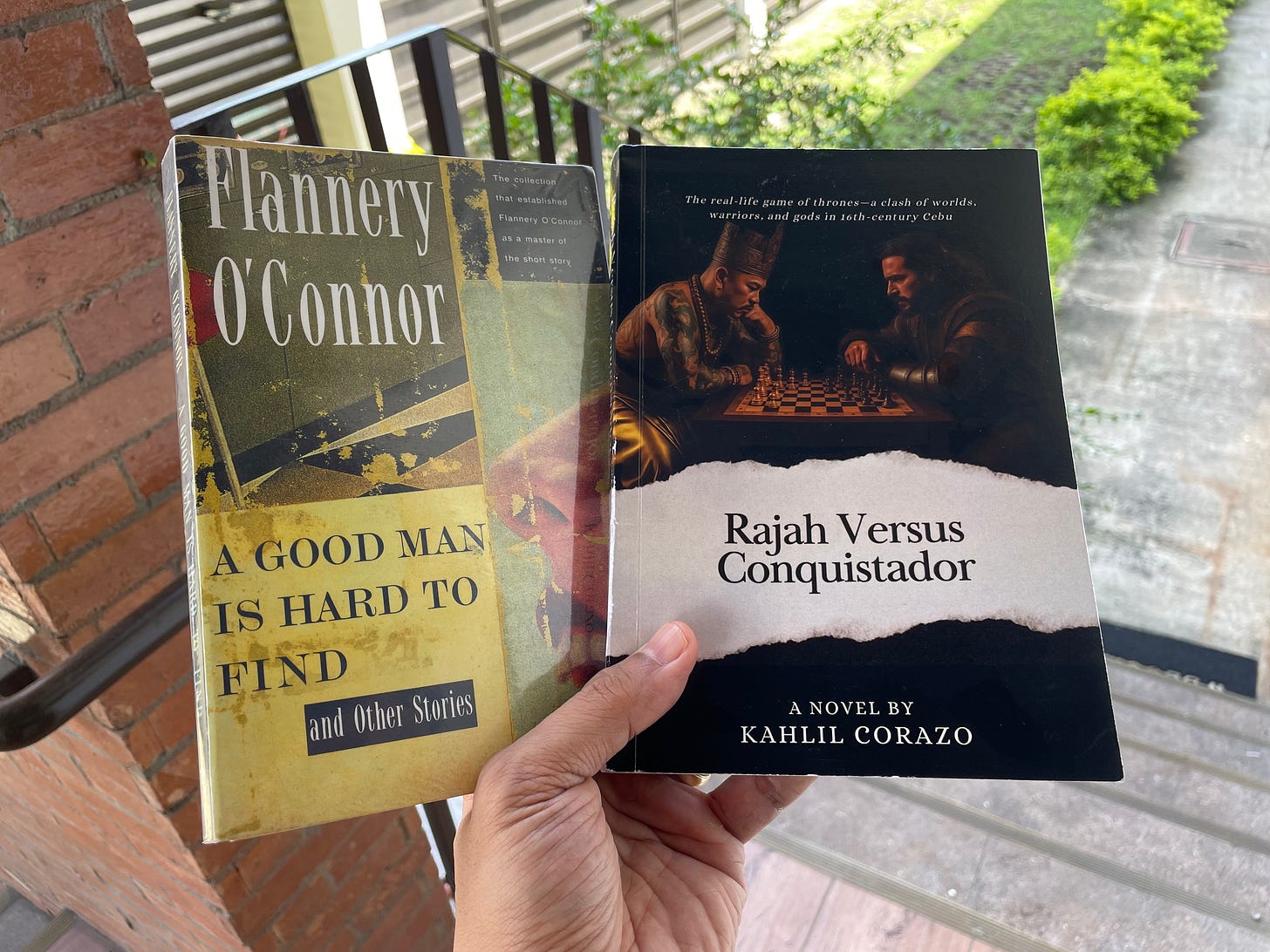

I remember the first time I did a coffee flight more than a decade ago at the invitation of my brother. I did not get it—similar to the first time I read A Good Man Is Hard to Find. Since then, I've become a coffee nerd, brewing speciality beans myself with implements that wouldn’t be out of place in a mad scientist's lab. I've also spent the past year writing my first novel, Rajah Versus Conquistador. I realized that my palate for stories has developed like my palate for flavor, and I now see and enjoy new layers in O'Connor's story just as I enjoyed that coffee flight in Madrid.

The Misfit

O'Connor's story has two main characters, the grandmother and The Misfit1. Over lunch, Jonathan explained that The Misfit is not a mere man. He referred to this section of the story (emphases mine):

"I was a gospel singer for a while," The Misfit said. "I been most everything. Been in the arm service, both land and sea, at home and abroad, been twict married, been an undertaker, been in a tornado, seen a man burnt alive oncet," and he looked up at the children's mother and the little girl who were sitting close together, their faces white and their eyes glassy; "I even seen a woman flogged," he said.

"Pray, pray," the grandmother began, "pray, pray..."

"I was never a bad boy that I remember of," The Misfit said in an almost dreamy voice, "but somewhere along the line I done something wrong and got sent to the penitentiary. I was buried alive," and he looked up and held her attention to him by a steady stare.

With this seeming immortality, The Misfit has been interpreted as the devil, or even a grotesque and perverted Christ-figure. Whatever he represents, The Misfit clearly has the psychological profile of a psychopath. The Misfit himself (or his dad) presents his diagnosis:

"Nome, I ain't a good man," The Misfit said after a second as if had considered her statement carefully, "but I ain't the worst in the world neither. My daddy said I was a different breed of dog from my brothers and sisters...

It makes more sense to me that The Misfit represents a type of person—the psychopath—rather than a supernatural being. O'Connor always writes about the encounter with supernatural grace. Rather than a symbol of evil—the absence of this grace—it makes more sense that The Misfit represents a type of fallen man and his own encounter with grace.

Iron Age Kings

My palate has been trained for this note in O'Connor's story since the the two main characters in my novel are both psychopaths: a precolonial Austronesian Orang Besar (Big Man) and a conquistador—Rajah Humabon and Ferdinand Magellan.

The psychopath was only medicalized and pathologized in the 20th century. Prior to modernity, he was simply the man unconstrained by taboo and fueled by high-octane will-to-power. Before law and order was institutionalized and depersonalized, he was both the threat to peace and the force that imposed the law: the barbarian, the hero, the tyrant, the king.

Ask yourself: what kind of man could become king in a world without the nation-state's monopoly of violence? Cultures that figured out how to weaponize him dominated those that didn't. In anthropology, this figure is called the Iron Age King, and he could be found in pre-colonial Africa and pre-Christian Europe. In Southeast Asia, he was called the "datu." Under his leadership, the seafaring Austronesians dominated the darker-skinned and shorter hunter-gatherers, and displaced them across the shorelines of what is now the Philippines, Indonesia, and Malaysia. By the time colonial officials and modern anthropologists recorded Southeast Asian cultures, these hunter-gatherers were only found in the hinterlands, still kingless, and frequent targets of the slave-raids of the lowlanders.

The Medieval Solution

My writing approach is similar to method acting. Everyday, I enter the mind of my psychopathic protagonists. The writing was its own adventure, because I did not know what would happen. Even though I was constrained by recoded history (it is a historical novel, after all), the rest of the story was yet to unfold. So I was surprised when Humabon underwent a conversion midway through the novel. After that, I couldn't bring myself to send him back to hell. This descent into darkness was the original plan, because the book's ending was the real-life massacre of Magellan's men through Humabon's cunning. This forced me to find a little crack of hope amidst the "red harvest," the final chapter's original title. The solution that came out of this constraint is actually more elegant and aesthetic than the original plan.

In Rajah Versus Conquistador, Magellan brings both Christ's grace and the cultural solution to the problem of the psychopath. It was apt that I reread A Good Man is Hard to Find in Madrid, because it was Medieval Christianity that found a way to ordain the psychopath towards Christian ends: he can now become a knight, a crusader, a good Christian king laying his sword at the feet of Christ. We cannot forget that these men were killers. This is hard for us to imagine now (I speculate why below) but even the work of the warrior—the work of ending lives—was Christianized.

Postmodernity's Trauma

There's a place called San Fernando in the island I grew up in, Cebu—the same island where Rajah Versus Conquistador takes place. It was only during the research phase of the novel, particularly the research of the world and the mind of the conquistador, that I found out who this guy was. Turns out, San Fernando is the quintessential warrior-saint. Why was he hidden from me?

My guess is that his disappearance has the same roots as postmodernism. The horrors of World War II and the Holocaust understandably made European philosophers fear the figure of the strong man. Their scapegoat was not only "metanarratives" but the king at its center who maintained this structure through his power. Postmodernity has abandoned the medieval model, leaving us with no pathway for their redemption. Today we only speak of containment and punishment.

But this abandonment has left us vulnerable. In the Philippines, we see this in figures like Duterte—now facing charges for crimes against humanity at The Hague. The modern world's only response to the psychopathic leader is legal prosecution, not transformation. Perhaps the salvation of "Duterte the monster" can only come through "Duterte the saint"—impossible as that may sound to contemporary ears.

The Grandmother

Both O'Connor's story and my novel reveal another crucial element: the role of women in this process of redemption or damnation. In A Good Man is Hard to Find, the grandmother recognizes The Misfit as one of her own, but ultimately fails to save him.

Rajah Versus Conquistador mirrors that structure but flips the outcome. Both Humabon and Magellan are saved not through ideology, but through the women around them. Humabon is first molded by Handuraw, a baylan (priestess) who channels his dangerous gifts toward power and ambition. Later, Paraluman confronts him with love—a love that transforms him.

Magellan, meanwhile, enters the story already formed. A Christian knight, not a mere killer but a crusader. He had Beatriz, his wife, and Queen Leonor—figures who, in the novel (and perhaps in real life), shaped him and ordained his sword. He also had models who he keeps referring to in the novel: San Fernando, El Cid, and the crusaders.

I modeled Humabon after the modern Big Men of the Philippines. I sensed that just as most of the local words that Pigafetta noted down 500 years ago are still being used in Cebu today, the actions of the locals recorded by the chronicler would make sense through the psychologies of Cebuanos today—the Big Man, for instance. I sensed that Paraluman's relationship with Humabon would be that of a dominatrix. When I mentioned this to Mitya, my writing coach, who happens to be a former journalist, he said that 90% of the politicians he interviewed had this kind of relationship with their wives!

This made me wonder whether Duterte could have been less unhinged if he had a stronger woman at his side. There's a memorable image of him right after he won the presidency wherein he visited the tomb of his mother and wept. Duterte fits the archetype I used for Humabon. However, unlike the novel’s Humabon, Duterte unfortunately did not have a queen to tame him.

I moved to Davao, Duterte's domain, five years ago, and I now understand why people here support him. Like 16th-century Sugbo, Davao in the 80s' was lawless. It needed a psychopath—one unbound by the taboos of the contemporary world and procedures of the nation-state—to impose order. Like the Iron Age kings of Europe, his salvation cannot be through the destruction of his essence, but, like San Fernando, its sanctification. In the case of the Southeast Asian Orang Besar, I sense that the woman plays a crucial role.

The Calling of the Psychopath

Sitting on that street in Madrid, where the legacy of those Christian knights still echoes in stone and story, I wondered if we've thrown away something essential in our rush to condemn the excesses of the past. Just as my palate had learned to distinguish the subtle notes in that morning's coffee flight—developed through years of brewing specialty beans—my year of inhabiting the minds of psychopathic characters had attuned me to something most people don’t even want to look at. The psychopath will always be with us—born into every generation, emerging in every culture. The question isn't whether they exist, but what we do with them.

O'Connor understood this. Her dark endings aren't nihilistic but diagnostic—they show us what happens when we fail to provide pathways for redemption. The Misfit's tragedy isn't that he was born different, but that no one knew how to help him become what he might have been.

Perhaps it's time to rediscover what medieval Christianity understood: that salvation is possible for everyone, even those we fear most. Perhaps some men are called to the path of violence and must find their salvation there. Perhaps the vocation of some women is to guide these men. The alternative—as O'Connor shows us in fiction and Duterte demonstrates in real life—is carnage.

O’Connor always capitalizes the T and the M in The Misfit.