The Three-City Problem of Meaningless Work

Work and Meaning Through the Eyes of Silicon Valley, Athens, and Jerusalem

This essay was first published two years ago in Luke Burgis’s Substack. You can still see in its comments section the notes of gratitude for the piece from around the world. Clearly, the problem of meaningless work transcends cultures and economies. I then published it in paperback, for which Luke wrote this blurb:

“Probing the philosophical and theological foundations of work—and not settling for easy: answers—is itself work, and a work that each of us should do. This essay by Kahlil Corazo is a wonderful place to start.” -Luke Burgis

I feel it’s about time I release this essay outside paywalls. It’s one of my best pieces of writing, and I occasionally revisit it to remind myself of what matters most in work and life. I hope it helps you as well.

John’s Crisis

John (not his real name) is a 38-year-old unmarried man who recently quit his high-paying job after 15 years, due to burnout. He is part of the FIRE (financial independence, retire early) movement. John reached his “FIRE number” some time ago. This means he had earned and invested enough money that he could live off his passive income. However, two weeks after quitting his job, John posted in the Facebook forum of our local FIRE community, saying that he was second-guessing whether he made the right decision. “I can’t figure out where and what to start, to fill my time - and now am contemplating whether I should go back [to holding a job], or start a business,” he wrote.

In response to John, I recommended two books: The Pathless Path by Paul Millerd and The Good Enough Job by Simone Stolzoff (I have become that type of guy). My endorsement was based not only on my first-hand appreciation of these books but from the thousands of grateful reviews from their readers. The popularity of these books shows that, like John, many are grappling with the purpose of their work.

Both books deliver. With the craftsmanship of a professional journalist, Simone tells stories of people who sought meaning in work, only to be trapped in a hamster wheel of unfulfilled desire. Paul speaks more from his own experience. From his journey and from conversations with people he helped step towards their own pathless paths, Paul offers ways of rethinking our relationship with work.

I eagerly read both books because I also went through a long process of seeking my professional vocation. There’s a recurring moment in the stories the books tell, that fateful day when one decides to leave “the default path.” Mine happened 15 years ago. After reading Paul’s and Simone’s books, my story sounds almost comically stereotypical and is pointless to relay here. What might be helpful is to distill and share the lessons from that journey. Living happily ever after with one’s work does not happen by itself.

This Is Water, These Are The Three Cities

The American novelist David Foster-Wallace opens his famous commencement speech, This Is Water, with this parable:

“There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says “Morning, boys. How’s the water?” And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes ‘What the hell is water?’”

I also recommended this speech to John because it helps unveil the often invisible underpinnings of problems related to meaning. The problem may not be the situation itself, but the lens with which we view the world. More recently, I’ve encountered a conceptual model that not only makes the water we swim in more visible but opens our minds to other bodies of water: Luke Burgis’s “Three Cities.”

In The Three City Problem of Modern Life published in Wired Magazine, Luke points out a kind of blindness that afflicts many of us today. Those of us who work in tech and business see the world through the lens of the metaphorical city of “Silicon Valley.” Its organizing principle is usefulness, and science and engineering are its aristocrats. “Athens” represents the humanities. The dominance of Silicon Valley has made Athens a vassal state where only the computable are recognized. Luke gives the example of the utilitarian logic in the countless white papers that lay out rationalized motivations behind movements like cryptocurrency. The third city, “Jerusalem,” represents religion. Today, Jerusalem feels distant from Silicon Valley. In this post, I’ll explore how the void this distance creates, and Silicon Valley’s domination of Athens, create an inhuman conception of work. I’ll also share both the pathologies and the cures that each city brings to the question of the meaning of work.

Work > Job

When you think about it, having a crisis of meaning in work is a luxury. For most of human history, the purpose of work was to not die. In ancient Greece, only the free citizens — i.e., those who were not slaves — had the luxury to philosophize. Thanks to the accelerating technological progress in the recent past, many of us now have this gilded burden. The metaphorical Silicon Valley deserves its dominance because it has given us this freedom.

This strength is also Silicon Valley’s weakness. While technology unceasingly progresses, human nature stays the same. As we speed toward the future, in awe of the power of our creations, we leave behind the answers that Athens and Jerusalem have given us for millennia.

For instance, ancient Greek philosophers had a clear distinction between servile work and the liberal arts. Josef Pieper explains in Leisure: the Basis of Culture,

“The liberal arts, then, include all forms of human activity which are an end in themselves; the servile arts are those which have an end beyond themselves, and more precisely an end which consists in a utilitarian result attainable in practice, a practicable result.”

In the utilitarian logic of Silicon Valley, servile work is the only kind of valuable work. Captured as I was inside this city, I used to feel guilty whenever I used my “productive time” on anything other than what could turn a profit. This guilt clearly comes from the morality of utility. This partnership of technology and the free market has undoubtedly produced a lot of good. Yet the emptiness I felt despite this abundance shows that my desires are much bigger than what the useful good can fill. The wisdom of Athens knew this and had a name for the boundlessness we desire. They called them the transcendentals: truth, goodness, and beauty.

Breaking Silicon Valley’s Monopoly

Stories, like the ones that Paul and Simone tell in their books, are like escape hatches from Silicon Valley’s monopoly on the meaning of work. In my own journey, it was the “lifestyle entrepreneurs” that showed me an alternative story. As I tried to build a life around a new script, it was principles like the ancient ones we explore here that helped me find my own path.

For instance, I can’t seem to stop calculating the return on investment of my time. Instead of forcing myself out of this mindset, I just expanded the meaning of “returns.” Today, spending an entire day reading and writing makes complete sense, yet this was unimaginable for me years ago. Similarly, days spent in nature are not merely a recharge in order to perform better at my job. After escaping the prism of utility, I can experience the outdoors as an end in itself.

Defining work as much broader than a job was also a kind of liberation. This meant that the money problem was separate from answering my professional calling. Paul and Simone warn us of the danger of equating our identities with our work. This tends to limit one to a single well-defined job, particularly one which your parents can describe.

Most of us still need to do some servile work to participate in the goods of civilization: at the minimum, food, shelter, and clothing for us and those who depend on us. At the same time, I’m certain that many of us feel the call to do something beyond mere survival and biological reproduction. If works like Liz Gilbert’s Big Magic, Stephen Pressfield’s War of Art, or Paul Graham’s How to Do Great Work resonate deeply with you, you know what I mean.

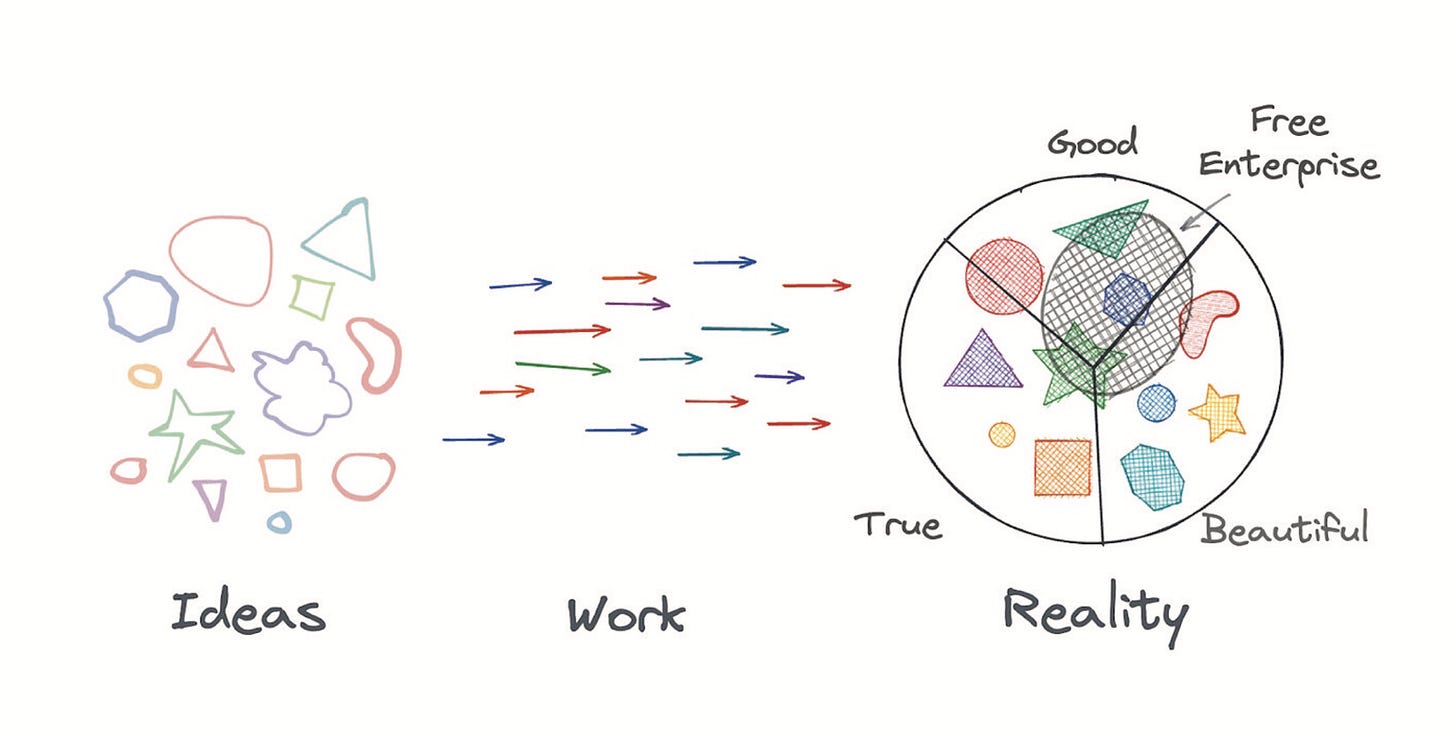

The lie perpetuated by the metaphorical city of Silicon Valley is that this professional vocation must be a kind of job, some kind of useful and servile work; that it must be somehow within the system of free enterprise; that its success must be proportional to the money it makes for us. However, if truth, goodness, and beauty are boundless, then only a fraction of their expressions must lie within the domain of the city of tech and money. All work has elements of truth, goodness, and beauty. But not all work falls within the system of free enterprise. Let’s draw that:

This diagram also shows a definition of our labors beyond the economic. Work is the human act that turns ideas into reality. Work is spirit expressing itself through matter. Work is the localized reversal of entropy. Jobs are kinds of work that allow us to participate in the exchange of goods and services.

If we define work and jobs this way, then there must be important work that lies beyond the system of capitalism. Monks and starving artists know this. Is there another option for those of us who are not monks and who like food?

The Athenian Path to F.U. Money

I like the people in FIRE community that John and I belong to. Most of them are humble and hard-working people. The most common pathway to FIRE in this group seems to be getting one or more high-paying jobs while being extremely frugal. The culture is a mix of Minimalism and financial geekery.

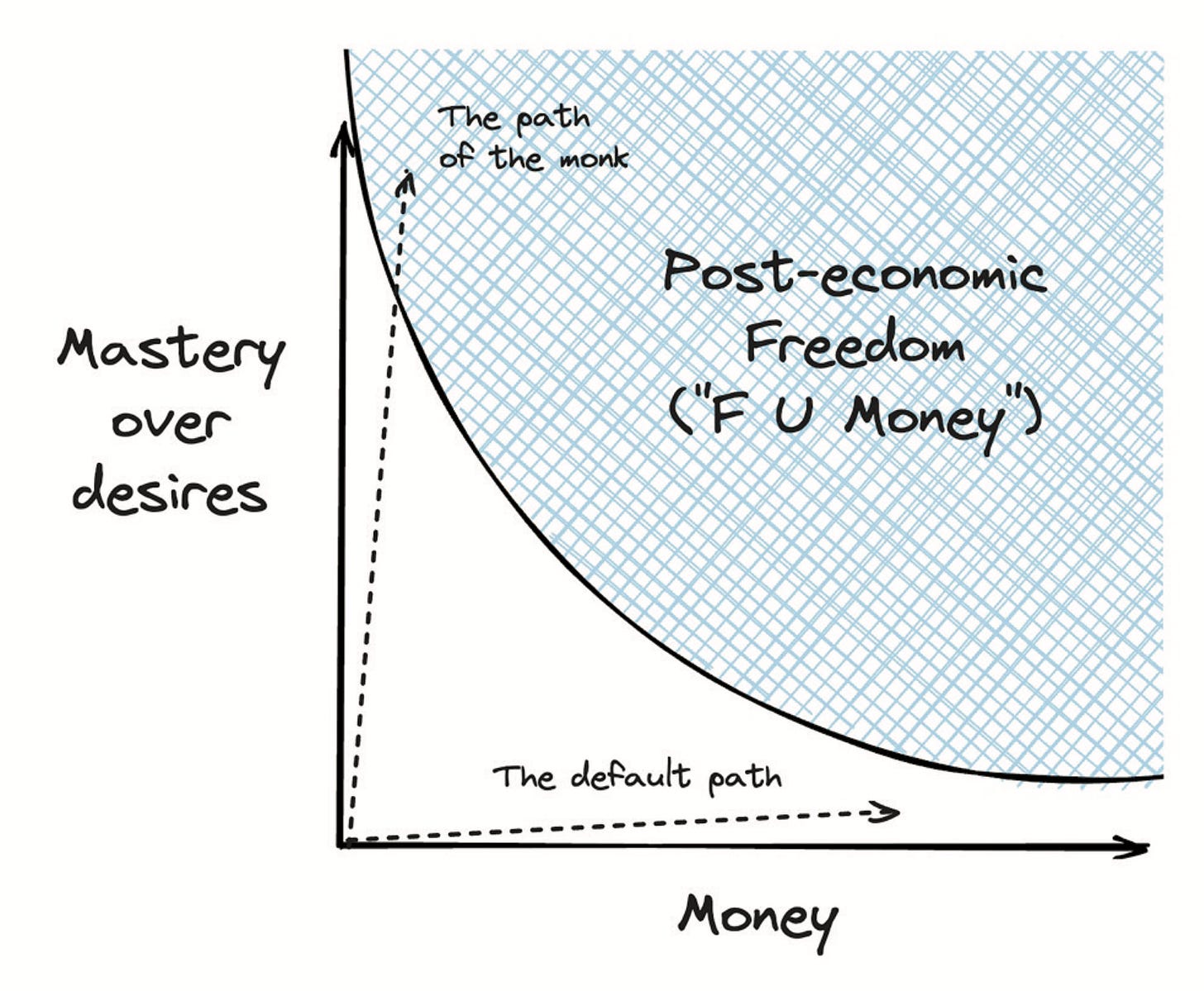

This stands in contrast with the hustlemaxx corner of Twitter, with its promises of fast cars, yachts, and submissive women. However, both groups essentially desire the same thing. What one calls post-economic freedom, the other calls “f*ck you money.” The advantage of FIRE is its adoption of Minimalism. This is a recognition that there are two axes in the vector toward financial freedom: money and desire. Let’s draw that:

If we are to apply the sophistication in personal finance that FIRE folk have to the mastery of desire, the first step is to recognize that there are different kinds of desire, and the mastery of each kind requires a different approach.

Animal: desire for survival and reproduction

Mimetic: desire that stems from our social nature

Transcendental: desire for truth, goodness, and beauty

We work because we desire. As beings with limited time and power, we have limited units of work. Working for a fancy car means that one or more books I am meant to write will never be written. There are worse ways to leak out my desires. The godlike efficiency of the market scrapes out each ounce of lust, loneliness, vanity, and indignation it can from us, bids them out algorithmically, and shapes our online worlds to expose more lines of desires it can excavate and mine.

This demonic side of Silicon Valley is new only in its efficiency. To Athens and Jerusalem, animal desire is a known problem with known solutions. Mastery over animal desire is classically called the virtue of Temperantia. The English “Temperance” is a bit misleading. In The Four Cardinal Virtues, Josef Pieper explains:

“For temperance, the disciplining of the instinctive craving for pleasure, was never meant to be exercised to induce quietistic, philistine dullness. Yet this is what is implied in common phrases about ‘prudent moderation.’ That implication comes to the surface when people sneer at the noble daring of a celibate life, or the rigors of real fasting.”

Pieper equates temperance to “selfless self-preservation.” It is the virtue that prevents animal desires from becoming gods that control one’s life.

Work as Training Ground For Eudaimonia

The Athenian playbook for growing in virtue sounds a lot like skill acquisition. The path is daily practice. The classic practice for Temperance is deliberate discomfort, or “mortification,” in the jargon of Christian asceticism. A lot of people use James Clear’s bestselling Atomic Habits to improve their lives, like exercising, curbing social media use, and losing weight. This is good, but it sounds small-minded compared to how Athens used the same techniques. To the ancient Greeks, Eudaimonia is the purpose of life. It is usually translated as “happiness” or “human flourishing,” but its meaning is clearest when we realize that Eudaimonia is no other than becoming brave, wise, just, and a master of oneself. The more virtuous you are, the less money you need to be free. Work is an abundant source for this training in virtue, alongside the demands of family and community.

Aiming for Eudaimonia is in itself a safeguard from small-mindedness. The pathological excess of Minimalism that I notice among FIRE folk is fear of undertaking big projects that risk their security, like starting a business or having children. Athens presents us with the countervailing virtue, whose name we have forgotten. We read in The Four Cardinal Virtues:

The noble, truly princely practice of spending lavishly in order to make splendidly visible some sublime thought—either in a solemn celebration, in sculpture, or in architecture—this virtue (for it is a virtue!) the Middle Ages called magnificentia. We no longer can describe it in a single word. But the relation of magnificentia to ordinary generosity, which belongs to the daily sphere of needs and requests, is the same, says St. Thomas, as the relation of virginity to chastity.

Mastery Over Mimetic Desire

Learning about mimetic desire was my biggest breakthrough in self-mastery since my introduction to practical virtue ethics in my teens. I first read about it in Luke Burgis’s Wanting, which is a great introduction to René Girard’s Mimetic Theory. Girard is a French literary critic and social theorist who has been called “the Charles Darwin of the Human Sciences.”

Girard first noticed the principle of mimetic desire as a pattern running through the great novels he taught. In Wanting, Luke unveils the power of mimesis in a similar way. He tells us stories that we can’t help but compare to our own experiences. Once mimetic desire is unveiled for you, you see it everywhere. Again and again, I’ve seen people tweet this same sentiment.

In the second part of the book, Luke gives us some ways to have some mastery over mimetic desire. We cannot choose the desires we copy from our models and rivals. However, we can design our environment (these days, this includes our social media feeds), and we can choose how we react to desires. This brings us back to the cardinal virtues, especially the temperance of saying no to ourselves and the fortitude to say no to our ingroup. Unveiling mimesis as the source of many desires is powerful in itself. If you pair this with a daily practice of meditation or prayer, knowing its name makes it easier to zoom out and examine those desires like an object in the palm of your hand, instead of an invisible force that envelops you.

My favorite tool from the book is “fulfillment stories.” These are occasions in the past where one took action and accomplished something that led to the happiness that comes from doing good, knowing truth, or beholding beauty. Recalling and relaying these stories helps you distinguish between your “thin desires” and “thick desires,” which makes it easier to design your life for the latter.

Hanging out with FIRE folk in real life, and biasing my online presence toward independent writers and Girardians is how I’m designing my life for my thick desires. My mimetic and competitive nature is gradually leading me to try to beat my models and rivals at Minimalism, personal finance, internet writing, and knowledge of René Girard. All is going according to plan.

Toppling the Athenian Ivory Tower

Girard has other astonishing observations. For instance, he points out how our current preference for the downtrodden over the powerful is unique in history. We take it for granted that you can present your story of being victimized to court or to the media, and people will generally side with you. If you claimed rights due to your victim status in the imperial courts of ancient Rome or China, you’d be laughed straight out of the palace.

This inversion of values, according to Girard, comes from the city of Jerusalem, both the literal and metaphorical ones. Girard says that the moral stance against sacrifice—which to him is a moral stance in favor of the weak—can be seen in Hindu sacred scripture (e.g., the Upanishads) as well as Buddhist thought. The world-changing revelation, however, came from the historical Jerusalem. The sacred scripture of the Jews is told from the perspective of the victim. This stands in contrast with ancient myths, which are told from the perspective of those who commit the sacrifice. To Girard, the summit of this revelation comes from the first-century rabbi Jesus of Nazareth. The Christian gospels tell us that he is a deity, yet he chose to be born to a poor family in a subjugated nation, and that he willingly let himself be sacrificed as a scapegoat—the “lamb of God.”1

We idealize the literal and metaphorical city of Athens above, as we contrast it to Silicon Valley. The fundamental option of the ancient Greeks, however, is the default one: they sided with the powerful. Pieper’s framing of how work was viewed by them reveals this. “Servile work” literally means the work of slaves, and “liberal arts” is what free men do. The unsavory aspects of Athenian society—slavery, the exclusion of women, and pederasty—also reflect the morality of slavemasters. Nietzsche noticed the same inversion of values brought about by Christianity—and famously despised it.2

This inversion of values gave nobility to jobs. Doing useful work is no longer relegated to slaves. Today, we admire the engineer and the entrepreneur as much and often more than the politician or the philosopher. The moral underpinnings of this civilization that brought us today’s unprecedented material wealth are centered around the son of God, who is also the son of a craftsman.

From Tertullian to Postmodernism

The three-city model we have been using here, according to its creator, Luke Burgis, was inspired by a question by Tertullian, a third-century Christian apologist. He asked, “What has Athens to do with Jerusalem?” Luke writes,

“By this he meant, what does the reason of philosophers have to do with the faith of believers? He was concerned that the dynamic in Athens—the reasoned arguments made famous by Plato, Aristotle, and their progeny—was a dangerous, hellenizing force in relationship to Christianity.”

Even in this metaphorical geography, we have xenophobic nationalists. We saw the myopia of Silicon Valley and of Athens. It is not surprising that Jerusalem, when closed off to the other two cities, also induces a kind of blindness.

Tertullian is one example. Above, we looked at temperance as freedom from the tyranny of animal desire. Tertullian, however, treats it like fortress walls to keep an evil world at bay. In The Four Cardinal Virtues, Pieper points out that this stems from dualist (”flesh is evil”) worldviews.

“That ‘wrong premise’ with its effects on ethical doctrine is particularly evident in the Montanist writings of Tertullian, who, by reason of his ambiguous status as a quasi-Father of the Church (St. Thomas speaks of him only as a heretic: haereticus, Tertullianus nomine), has continued to this day as the ancestor and the chief witness of that erroneous evaluation of temperantia.”

In The Weight of Glory, C.S. Lewis also made the same observation, but he blames Kant and the Stoics.

In the world of work, this wrong premise translates to a disdain for business and other “worldly” affairs. God punished Adam and Eve by requiring that they get jobs. “By the sweat of your brow will you eat your food until you return to the ground,” we read in Genesis.

Postmodernist philosophy is the post-Christian continuation of this contemptus mundi. According to Cleo Kearns, postmodernism was a response to the unprecedented scale of violence of the European world wars and the holocaust. They blamed “metanarratives,” including reason itself, children as they are of Nietzsche. When we view work solely from each of the three cities, it is still meaningful, though arguably in a grotesque way. Postmodernism is the true meaninglessness because it denies meaning itself.

My guess is that postmodernism is the invisible water we are swimming in today. My main quibble with The Pathless Path and The Good Enough Job is that both are too embedded within this body of water. Both Paul and Simone recognize that work can become a god that eventually devours its worshipers. But their solution is the same as the postmodernists: to have no strong gods. Paul tells us,

“The answer, my dear reader, is simple. You start underachieving at work.”

Thankfully, Jerusalem offers other answers.

Work Through the Eyes of Jerusalem

John’s suffering after he gained his financial freedom and early retirement reminds me of Bree in C.S. Lewis’s The Horse and His Boy. Bree is a talking stallion from the magical land of Narnia who was captured and lived as a warhorse but later escapes with the help of Shasta, the protagonist of the book. In one scene, Bree reflects on the burden of new freedom:

“But one of the worst results of being a slave and being forced to do things is that when there is no one to force you any more you find you have almost lost the power of forcing yourself.”

If I knew John in real life, I’d have beer with him instead of merely recommending books. It was through friendship that I entered the city of Jerusalem, so it is the pathway I know best. The first step would be to accompany John in discerning what he is supposed to do with his newfound freedom. I would literally sit beside him in silence in a church or some other sacred space, as I have done with some friends, and as friends of mine did at the start of my journey back to Jerusalem. Then perhaps I’d invite him to a silent retreat.

There is a Bree in each one of us. It is possible to regain the liveliness lost from falling into a vicious cycle of fear, desire, and disappointment, just like a wild stallion can learn to trust its handler. But the transformation is not instantaneous like Silicon Valley’s dopamine slot machines. Time flows more calmly in the city of Jerusalem.

Jerusalem has been described as “a port city on the shore of eternity.” This description also applies to the metaphorical Jerusalem. The timelessness and otherworldliness of Jerusalem allow us to transcend the ecosystem of assumptions of the times and places we happen to be born in.

When John eventually gets into a rhythm of daily reflection, I’d invite him to this port city, which can give him a bigger picture to take inspiration and motivation from. The same city can also provide Paul and Simone with an alternative body of water from which they can view radically different solutions to the problem of work and meaning.

Take, for instance, the style of Christian living preached by Josemaría Escrivá, a 20th-century Spanish priest. He spoke mainly to followers of the Nazarene, reminding them that work is their participation in redeeming the world. Escrivá points out that Jesus’s public ministry was only the last three years of his life. Before that, he already started his work of redemption through his ordinary life in Nazareth, with his family life, his friendships, and his work at Joseph’s workshop. Most of our lives consist of these ordinary joys and sufferings, including the joys and sufferings of our work.

To everyone open to the message of Jerusalem, Christian or not, Escrivá offers perspectives not found in Silicon Valley or Athens. For example, on the dangers of work so meaningful that it might consume you. Paul Graham’s rock anthem of an essay, How to Do Great Work, speaks to those of us who treat work as a central part of our lives. Liz Gilbert’s Big Magic presents a devotional relationship with one’s creative work. To the risks that Paul and Simone alert us in treating work as such, Escrivá responds with a message from Jerusalem. We need not fear the power of work. Our muses and our masterpieces also bow to the name of the Almighty.

In contrast to Tertullian and postmodernism, Escrivá starts with the goodness of human realities. In the homily Passionately Loving the World,3 he says,

“That is why I have told you so often, and hammered away at it, that the Christian vocation consists in making heroic verse out of the prose of each day. Heaven and earth seem to merge, my children, on the horizon. But where they really meet is in your hearts, when you sanctify your everyday lives…”

Silicon Valley equates work to a job, one’s role in the system of free enterprise. Escrivá does not deny this, but he defines work in a broader sense, from the eyes of Jerusalem: it is our participation in the work of creation. In response to the quote from Genesis above, Escrivá points out that before the fall, God gave Adam and Eve stewardship over the world. “God blessed them and said to them, ‘Be fruitful and increase in number; fill the earth and subdue it. Rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky and over every living creature that moves on the ground.’” Having a job might be an unavoidable burden, but our ability to work is a gift.

Works Cited

Armitage, Duane. Philosophy’s Violent Sacred: Heidegger and Nietzsche through Mimetic Theory. 1st ed., Michigan State University Press, 2021.

Burgis, Luke. “The Three-City Problem of Modern Life.” Wired, 28 Aug. 2022, https://www.wired.com/story/technology-philosophy-three-city-problem/.

Burgis, Luke. Wanting: The Power of Mimetic Desire in Everyday Life. St. Martin’s Press, 2021.

Clear, James. Atomic Habits: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad Ones. Avery, 2018.

Escrivá, Josemaría. In Love with the Church. Scepter, 2008.

Gilbert, Elizabeth. Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear. Riverhead Books, 2015.

Girard, René. The Scapegoat. Trans. Yvonne Freccero. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986.

Graham, Paul. “How to Do Great Work.” July 2023, http://paulgraham.com/greatwork.html.

Kearns, Cleo. “The God of Abraham and the Spirit of Philosophy: A Primer on the Engagement of Postmodern Philosophy with the Abrahamic Scriptures.” Cleo Kearns (blog), 10 June 2023, https://cleokearns.substack.com/p/introduction-to-the-bible-for-non.

Lewis, C. S. The Horse and His Boy. HarperCollins, 2008.

Lewis, C. S. Weight of Glory. HarperOne, 2009.

Millerd, Paul. The Pathless Path: Imagining a New Story for Work and Life. Paul Millerd, 2022.

Pieper, Josef. Four Cardinal Virtues, The: Human Agency, Intellectual Traditions, and Responsible Knowledge. Translated by Richard Winston, Clara Winston, Lawrence E. Lynch, and Daniel F. Coogan, 1st ed., University of Notre Dame Press, 1990.

Pieper, Josef. Leisure: The Basis of Culture. Foreword by James V. Schall, 1st ed., Ignatius Press, 2009.

Pressfield, Steven. The War of Art. Edited by Shawn Coyne, Black Irish Entertainment LLC, 2011.

Stolzoff, Simone. The Good Enough Job: Reclaiming Life from Work. Portfolio, 2023.

Wallace, David Foster. This Is Water: Some Thoughts, Delivered on a Significant Occasion, about Living a Compassionate Life. 1st ed., Little, Brown and Company, 2009.

Thanks to Luke Burgis for publishing this essay, to Raymond Ng for the editing, and to all who posted comments and sent private messages in response to it—writers like me also need to be reminded that our work is not for nothing.

Girard presents this idea in several of his books. For instance, see Girard, René. The Scapegoat. Trans. Yvonne Freccero. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986.

For a presentation of Girard’s critique of Nietzsche and postmodernist philosophy, see Armitage, Duane. Philosophy’s Violent Sacred: Heidegger and Nietzsche through Mimetic Theory. 1st ed., Michigan State University Press, 2021.

You can find this homily online and in several published books, e.g., Escrivá, Josemaría. In Love with the Church. Scepter, 2008.