"The West" Is a Terrible Name but a Great Invention

Explanations from David Deutsch and René Girard

If you're extremely online, you might have noticed how the internet right wing has been calling for a defense of "the West" in the past few years. After spending fourteen months writing a novel on the historical and bloody encounter between a European conquistador and a Southeast Asian rajah, I have to say that I now see their point. However, I think these defenders of Western civilization are falling into the same underhanded tactic they accuse their enemies on the left of exploiting: an appeal to identity instead of truth.

To extract the universal wheat from the particular cultural chaff of Europe and the Anglosphere, we need to ask: what made the West great?

The best answers I encountered have been from David Deutsch and René Girard.

What do we mean by "the West"? Here's Deutsch's explanation in his 2011 book The Beginning of Infinity:

But the sea change in the values and patterns of thinking of a whole community of thinkers, which brought about a sustained and accelerating creation of knowledge, happened only once in history, with the Enlightenment and its scientific revolution. An entire political, moral, economic and intellectual culture – roughly what is now called ‘the West’ – grew around the values entailed by the quest for good explanations, such as tolerance of dissent, openness to change, distrust of dogmatism and authority, and the aspiration to progress both by individuals and for the culture as a whole.

Deutsch proposes the label "dynamic societies" for those with these characteristics. He contrasts this with "static societies."

Contrary to conventional wisdom, primitive societies are unimaginably unpleasant to live in. Either they are static, and survive only by extinguishing their members’ creativity and breaking their spirits, or they quickly lose their knowledge and disintegrate, and violence takes over.

How did the West come to be? Here is Deutsch's guess:

Our society in the West became dynamic not through the sudden failure of a static society, but through generations of static-society-type evolution. Where and when the transition began is not very well defined, but I suspect that it began with the philosophy of Galileo and perhaps became irreversible with the discoveries of Newton. In meme terms, Newton’s laws replicated themselves as rational memes, and their fidelity was very high – because they were so useful for so many purposes. This success made it increasingly difficult to ignore the philosophical implications of the fact that nature had been understood in unprecedented depth, and of the methods of science and reason by which this had been achieved.

Girard traces the origin of the West farther back in history and sees its influence on societies it has touched in modern times.

This influence has been so pervasive, that it is hard to see the world through the eyes of our pre-Westernized ancestors. Because of this influence, we recoil at the thought of ritual human sacrifice and slave raiding. Yet, to truly inhabit the mind of the 16th-century Southeast Asian strongman of my novel, I had to imagine what it must be like to see violence not only as a necessity, but as precisely the path to power.

Then I realized that I did not have to imagine that hard because this is still true today. As I write this, a former president of my country, Rodrigo Duterte, is detained in the Hague—at the old heart of the West—for crimes against humanity. He comes from a long line of Southeast Asian strongmen. His bodycount is actually tiny compared to his predecessors; the 1965 massacres in Indonesia, for instance, is estimated to have had around half a million victims.

Girard is known for theorizing the "scapegoat mechanism," a collective instinct among humans that evolved in response to the dangers brought by the greater cognitive powers developed during the process of our hominization. I won't rehash his explanation (you can read some of my previous posts or you can ask your robot assistant), but I'd like to highlight the universal problem of scapegoating, how societies have historically justified collective violence against minorities and outcasts, how the West began to unveil these lies, and the consequences of this revelation. This will give us a clearer idea of how moral innovations can transform societies beyond their origins.

In his 1982 book The Scapegoat, Girard presents examples of scapegoating in historical times, like the repeated massacres of Jews and the literal witch hunts in Europe. Taken by themselves, we might think that Medieval Europeans were particularly prone to scapegoating. However, if we look at the pogroms throughout the history of Southeast Asia, we will see that scapegoating is a universal problem, and that lynchings and collective murders appeared to increase in modernity precisely because our lens have become unclouded. We no longer believed in the myth of the guilt of the witches and the Jews.

On the other hand, these killings were justified through the archaic lens of myth. For instance, the Balinese myth of Rangda and Barong tells of Rangda, an old woman with supernatural powers (a witch, basically), who presents her daughter to become a wife of the king. The king rejects Rangda, so she takes vengeance by unleashing a plague on the village. The villagers try to escape, but she and her child-minions follow them and kills a new born baby. An emissary of the king tries to kill her but fails. The emissary then transforms into Barong, a giant serpentine creature (a dragon, basically). Barong leads a group of villagers to attack Rangda, but they fail and die. A priest of Barong revives them with holy water, and they attack Rangda again.

If we apply the analysis we use on modern state propaganda on this myth, it is clear that the story of Rangda and Barong is designed to exculpate the witch killers. The guiltier the witch is, the more justified is their murder. Supernatural powers had to be ascribed to her so that she can be blamed for the plague, similar to how the ability to poison an entire town was ascribed to Medieval European Jews.

The tendency to blame scapegoats is like an incomplete scientific mindset. There is already a sense of cause and effect, but it lacks what Deutsch calls "good explanations." For instance, if you were part of some upland communities in Mindanao that continued to escape modernity—as recently as a couple of decades ago—you would have known to stay inside your house if a man inexplicably lost a wife or a child to some disease. He was expected to exact vengeance… on the first person he would see along his path of rampage. He was ignorant of germ theory.

When these inexplicable deaths happens to an entire village—e.g., a plague—it is usually blamed on those easiest to kill: minorities or old women. Times of chaos are also an opportunities for those who wish to topple the current power structure. The king's rivals deploy their own propaganda and execute a coup. One of Girard's favorite examples is the myth of Oedipus, the king of Thebes in ancient Greek mythology. Since Oedipus committed the gravest sins of incest and patricide, his lynching is justified. To Girard, the myth of Oedipus is a record of an actual lynching of kings distorted throughout time, just like the myth of Rangda and Barong.

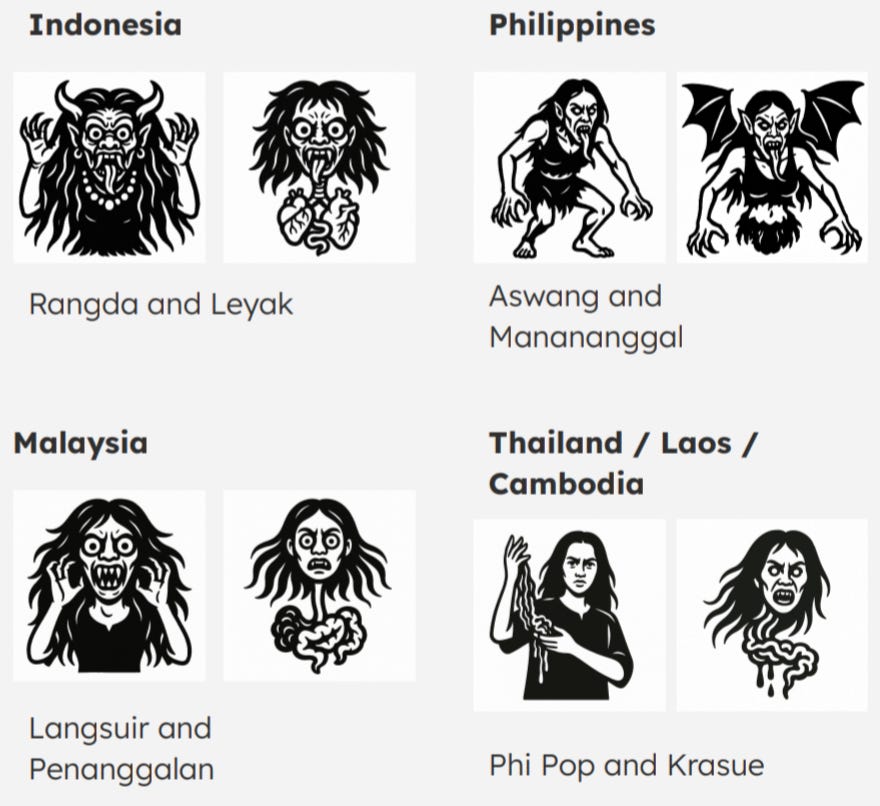

This reading explains the prevalence of female monsters in Southeast Asian myths. The women who eats babies or entrails, like the Aswang and Phi Pop, were demonized after they were lynched. The flying female monsters with exposed internal organs were the dismembered victims of collective murders, remembered as monsters instead of innocent scapegoats by the descendants of their killers. We Southeast Asians have supreme respect for our ancestors and will always preserve their good name.

The West is not that far ahead in unveiling the lies in their myths. It is only in the past few years that their supreme mythmaker, Hollywood, has started to realize that their witches were never guilty after all, and that it was all state propaganda. Hollywood should also strip them of supernatural powers, but that would likely produce weird arthouse films instead of blockbusters.

Girard theorized that this tendency for scapegoating is embedded in the human psyche through evolution. However, we are also (more or less) conscious and free beings. At some point in the past, we started to see the lie behind the guilt of witches. Thus the word "scapegoat" was coined.

To Girard, this unveiling stems from the West's preferential option for the downtrodden. By default, knowledge is created by the powerful. With this epistemology, the killing of minorities for the sake of society's survival is always written from the point of view of the murderers and their descendants. Before and outside the West, myths develop over time by stacking more and more guilt on the scapegoat, which justifies the murder committed by one's ancestors.

Girard traces this preferential option for the downtrodden back to the sacred scripture of the Jews and especially to the first-century rabbi Jesus of Nazareth. His story, like those of the prophets in Jewish scripture, follows the arc of the scapegoat. Chaos erupts in Jerusalem. The people in power and the mob are one in heaping guilt upon the rabbi. He ends up sacrificed, and order is restored.

Girard points out a key difference between myths and the scripture of the Jews and Christians. Myths are always written from the point of view of those who committed the murder, thus the distortions. The scriptures of the Jews and Christians, in contrast, are written from the point of view of the scapegoat. This perspective prevents the concealment of the truth: the prophets and Jesus are innocent.1

In The Beginning of Infinity, Deutsch wonders why Athens did not become a dynamic society, as it had respect for truth and a nascent tradition of criticism. The answer is plain to see after Girard's explanation. The Athenians were still trapped in the epistemology of power. One of their greatest thinkers, Aristotle, believed that some men are born to lead, and others are born to be slaves. This worldview is also expressed in women's fundamental inferiority in Athenian society. In contrast, Paul of Tarsus, one of Jesus's early followers, writes this:

There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus.

The equality of all men and women, regardless of social class, ancestry, or creed, is the fundamental moral choice behind a society based on the epistemology of truth instead of deceitful harmony or raw power.

The realization and acceptance that we are born with this darkness in our hearts is the first step to overcoming it. To Girard, this is "conversion." The antidote to the lynching mob are individuals who see Satan not in the witch but as the animating spirit that binds and moves the crowd—that binds and moves us. This is a small part of the gospel that was birthed in the Near East. It spread worldwide through its encounter with and its transformation of the West's indigenous cultural innovations (e.g., Roman rule of law). Humanity owns these innovations, not just the people who happen to be descendants of the societies that were the fertile soil of its flowering.

In his 2019 book Dominion, the historian Tom Holland makes the same point trough history instead of anthropology.

Ehrenreich's "Blood Rites" traces these human group instincts even further back. Humans evolved from a prey species but along the way transformed into predators. This demanded profound psychological changes, which are not fully resolved in people today. The prevalence of predatory entities in primitive religions and the universality of human sacrifice likely stem from this foundation. Scapegoating is likely a remnant of an ancient prey group behaviour where an individual is offered to the predator so that the rest can survive.

So clearly written, because it skips caveats to show a clear undeniable pattern that many of us are taught to file under “taboo”.