Things Hidden Since 1521 (Frankfurt Book Fair Talk Practice Run)

Novel-writing as ethnography of precolonial Philippines

After writing Rajah Versus Conquistador, my anthropology background immediately kicked in. That entire experience felt very… ethnographic. In the field of anthropology, ethnography is how you create knowledge: direct experience of a society and creating your models and documentation from that experience. Anthropologists spend months to years living within the culture of the world they are studying. One of my teachers, for instance, almost got killed while doing fieldwork among the Banwaon, an indigenous group in Agusan del Sur, when his research on state militarization and local leadership drew him into the same networks of danger he was studying.

My “fieldwork” sounds pretty lame compared to Sir Gus’s, but I have to ask: did living inside the mind of a 16th century Orang Besar—a Southeast Asian Big Man—almost daily for over a year in order to write RVC give me an intuitive knowledge of 16th century Sugboanon culture the same way ethnographers gain an intuitive knowledge of the extant cultures they study through their immersion? And if novelists can gain ethnographic knowledge of the worlds they recreate in their novels, then can novels be “thick descriptions” of these cultures?1

I have multiple drafts of a paper I’m writing on these questions, which I find so fascinating. I’m putting this exploration ahead of my other scholarly projects because my memory of that experience is beginning to fade! Writing that novel was one of the strangest and most magical journeys I’ve undergone, and both the scholar and essayist in me need to write about it and make sense of it.

As always, I’m working with the garage door open to maximize serendipity and to send out an invitational signal to others exploring similar or adjacent questions. My October 18th talk at the Frankfurt Book Fair is very much in this spirit. This post is also an invitation. Below is a recording of a practice run and an edited transcript. I’d love to hear your feedback, thoughts, and questions!

Slides and Edited Transcript

Hello, my name is Kahlil Corrazo. I’m here with Robin Sebolino. We are both historical novelists from the Philippines.

I released my first novel, Rajah versus Conquistador, last May. It is about the encounter between Rajah Humabon of Cebu and Ferdinand Magellan back in 1521. Robin has written Bells and Incense and Vassals of the Valley, historical novels set in Colonial Philippines.

Three Questions to Think Like Historians

Before I tell you what I discovered in writing this novel, I want to invite you to think like historians for a moment. Here are three questions, and I’d like you to speculate on what the answers could be:

Why did Magellan fight a suicidal battle?

Why did Humabon massacre his allies?

What was the role of women in the events of 1521?

Keep these questions in mind. By the end of this talk, I’ll share what historians and eyewitnesses speculated, and what I discovered in the process of immersing myself in the world of the novel.

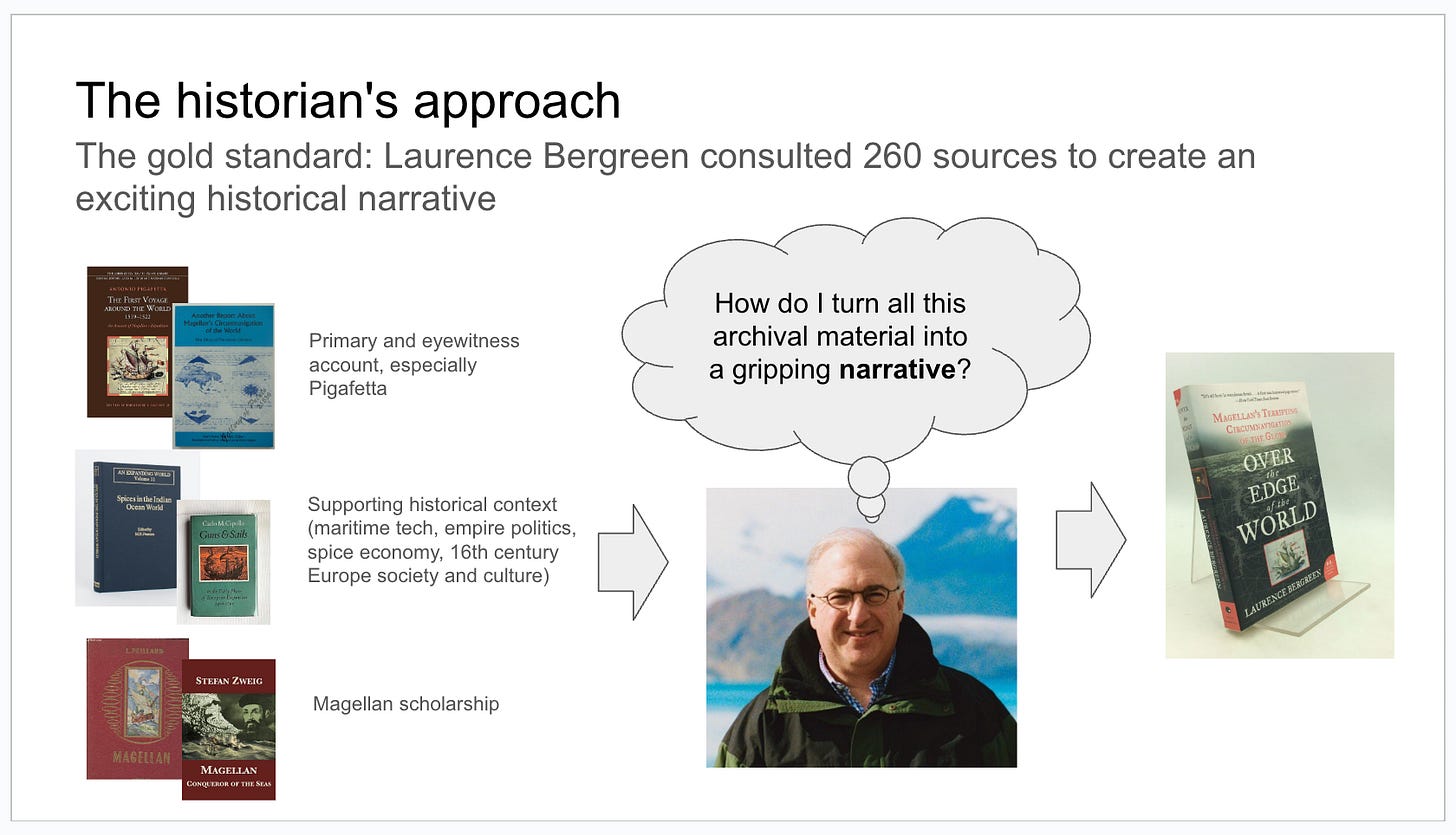

The Historian’s Approach

Laurence Bergreen’s Over the Edge of the World was my main source for the Magellan side of the novel. I think this is the gold standard—I like this book a lot. If we look at his bibliography, there are around 260 sources there. The question for him was: how do you turn all these sources—primary sources, eyewitness accounts, and what we know about maritime technology, the politics of empire, the spice economy, and 16th-century European society—into a gripping narrative? I think Bergreen succeeded in doing that. This is the most exciting account of Magellan’s voyage that I’ve seen.

But my question was: how would a novelist approach this? More specifically, what was the Cebuano side? How were they thinking? I also wanted to see how Magellan thought. A historian could not answer that. Bergreen was very disciplined—he only spoke of what was probable and what we actually knew, what was documented. But a novelist is freer in speculating on what was happening inside the minds of both Magellan and Humabon and the people around them.

The Novelist’s Approach

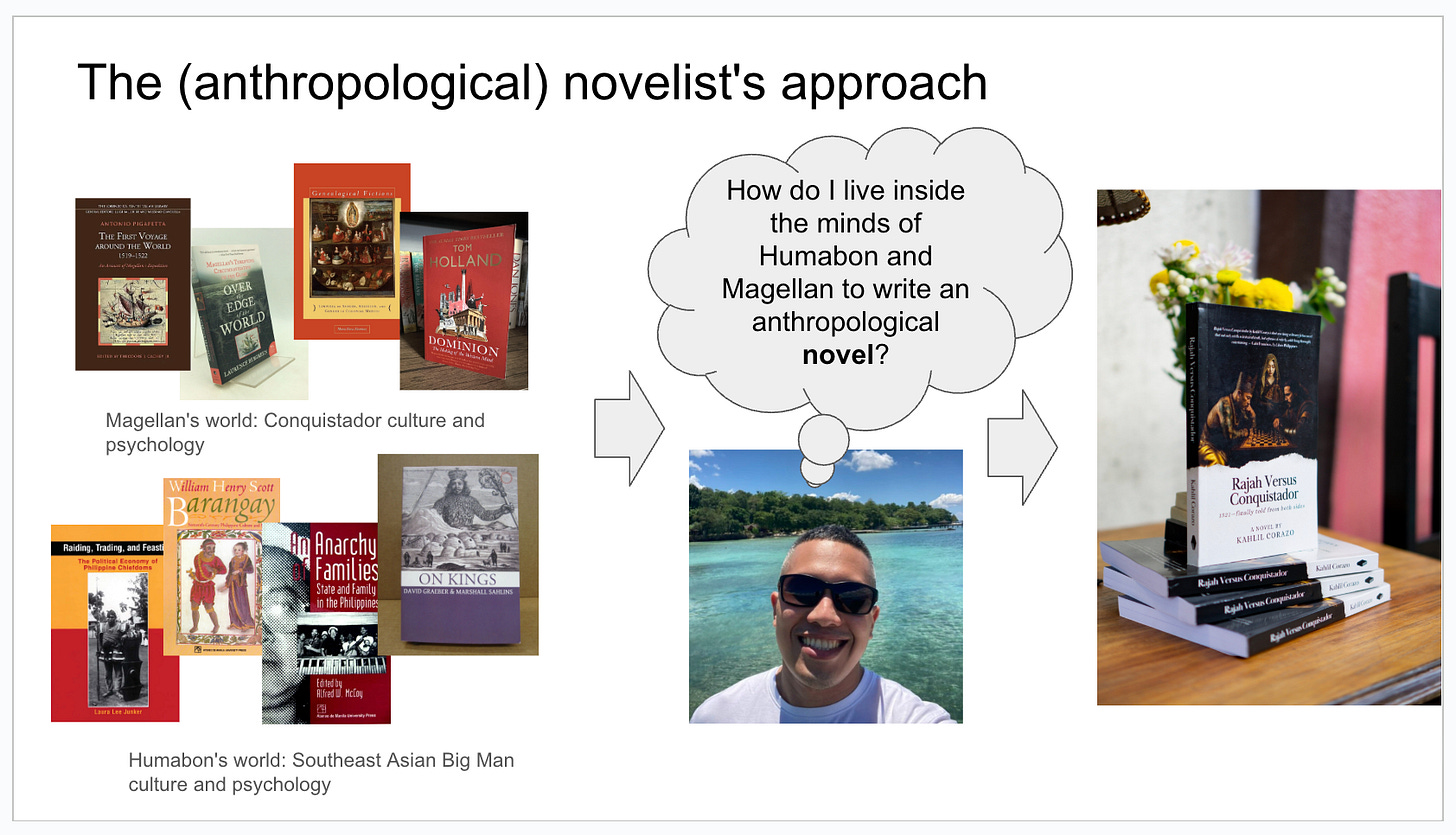

I tried to understand Magellan’s world—how a conquistador, a 16th-century hidalgo from the Iberian Peninsula, would think. I didn’t only look at the primary source (Pigafetta) or the history books like Bergreen’s account, but also other aspects of the culture.

For Humabon’s side, we don’t have an equivalent to Pigafetta, but we do know how leaders like him thought. The moment I thought this could be written was when I realized that Humabon is a kind of person I knew. I knew this person from scholarship, particularly the scholarship of the Austronesian big men, and also from my experience of being around these people as I grew up in Cebu City.

I consulted books like Raiding, Trading and Feasting by Laura Junker, books by William Henry Scott about the 16th-century Philippines, and studies on the anthropology of premodern kingship. What was the culture back then? What was the psychology of a leader, a chieftain, a rajah back then?

Language as a Bridge to the Past

But not only that—Pigafetta wrote down 160 words in 1521… and I could understand most of them! There’s this hypothesis called the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, which says that people view the world through the lens of their language. If you share a language, you share a kind of worldview. If there’s truth to that, then I could actually share a worldview with the 1521 Cebuanos! My experience of the culture of Cebu is also an input to recreating 1521 Cebu.

Living as a Rajah and a Conquistador

This was my process of creating the story: understanding the culture of 16th-century conquistadors—in particular, I made use of the phenomenon of limpieza de sangre (purity of blood), one of the earliest official racisms, and the impact of Christianity on culture, particularly through the interpretations of Nietzsche, René Girard, and Tom Holland. That was the Magellan side. And then the figure of the Big Man for Humabon’s side, plus my experience of modern culture.

Now you understand why my approach was different from Bergreen’s.

The Anthropological Question

Right after I finished writing that novel, my anthropology background kicked in. My scholarly work in the past few years has been focused on the intersection between the figure of the Austronesian big man (the orang besar) and René Girard’s scapegoat mechanism.2 Since my background is in anthropology, I had to ask: that experience of writing the novel felt very ethnographic. Did I actually produce ethnographic knowledge by writing that novel—ethnographic knowledge of 16th-century Cebu?

To answer that, I need to show you how some scholars have used both ethnographies and novels as sources of cultural theories.

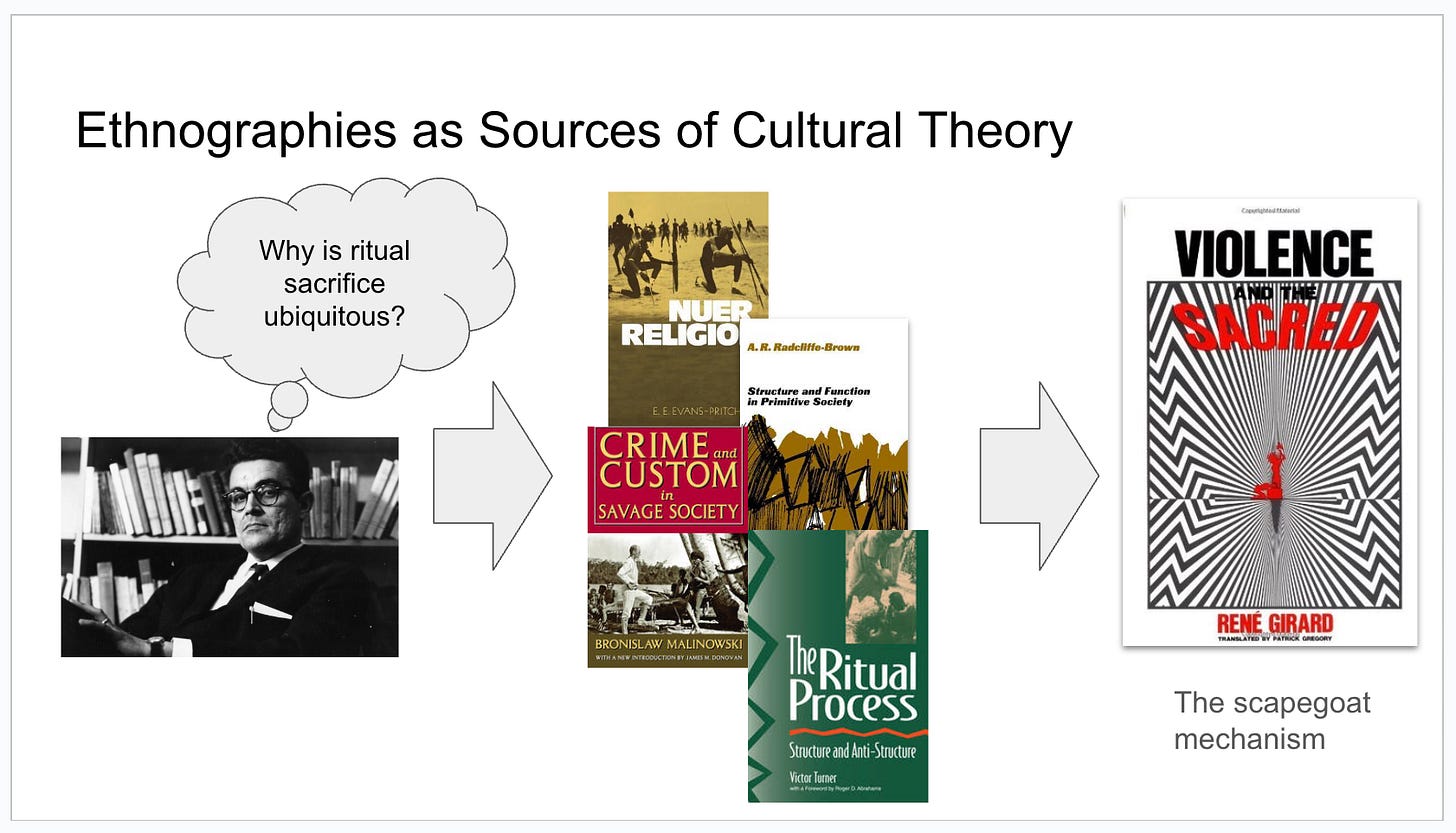

Ethnographies as Sources of Cultural Theory

The scholar whose work I’ve been focusing on in the past years is René Girard. One of his key theories is the scapegoat mechanism. That theory was built through his reading of 20th-century British ethnographers like Malinowski and Radcliffe-Brown, and also through analysis of myths. This is an example of how a scholar could make use of ethnographies to answer a question—in this case, why is ritual sacrifice present in all pre-Axial Age societies?

Novels as Sources of Cultural Theory

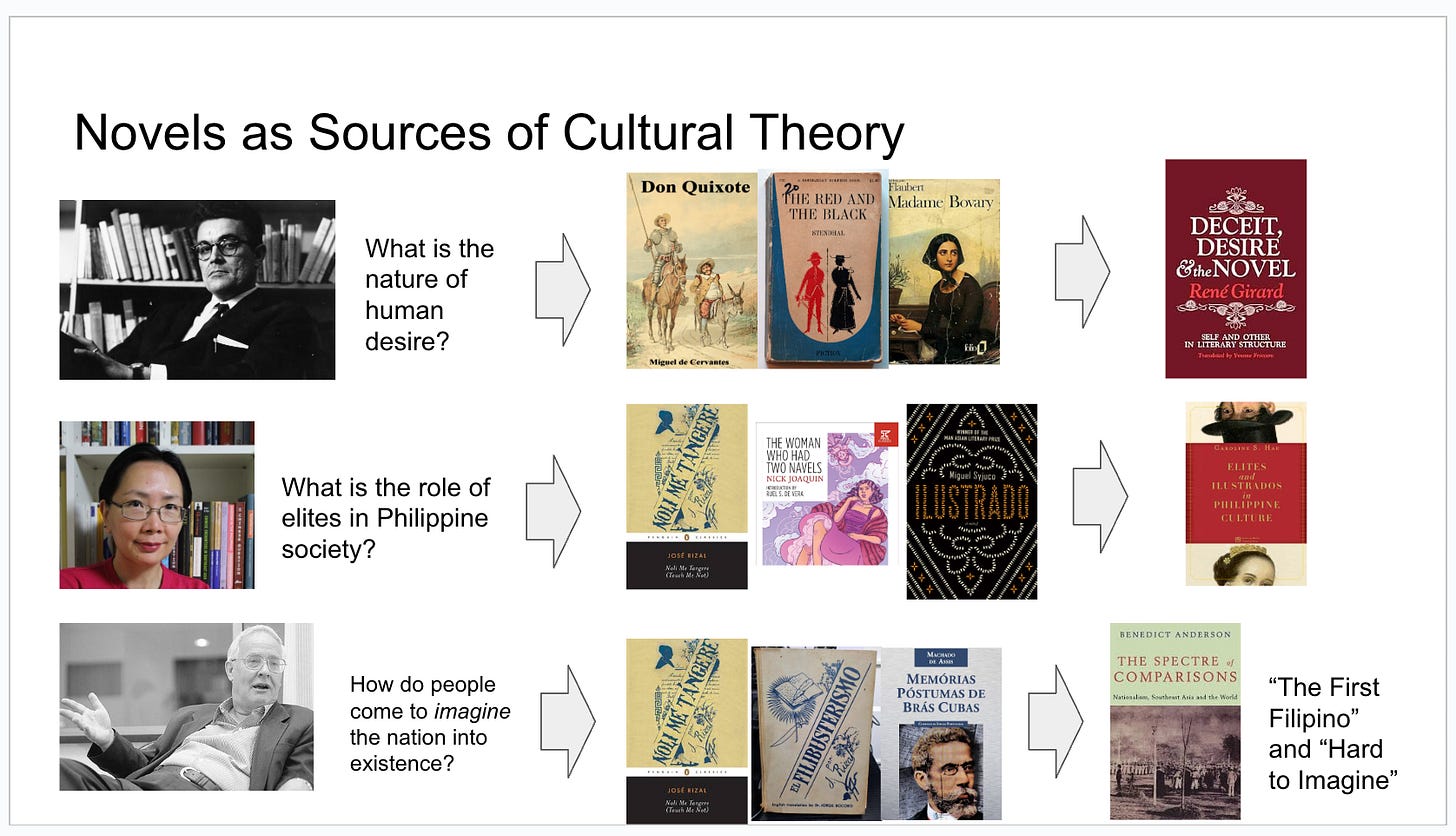

But we also have examples of him using novels as a kind of ethnography, as a source of cultural theory. René Girard is better known for his theory of mimetic desire, which is an explanation of the nature of human desire. He used novels for that—Don Quixote, books by Stendhal and Flaubert.

I was looking at my library and saw other examples. Scholar Caroline Hau, in her book Elites and Ilustrados of Philippine Culture, used novels like Rizal’s Noli Me Tangere, Nick Joaquin’s The Woman Who Had Two Navels, and Miguel Syjuco’s Ilustrado as sources for cultural theory—to answer questions about the role of elites in Philippine society.

Benedict Anderson did the same thing in his book The Specter of Comparisons, particularly in the chapters “The First Filipino” and “Hard to Imagine.” The question was: how is the nation imagined into existence? He used novels to answer the question.

Answering the Three Questions (Discussion and Q&A)

Now that we’ve established that both novels and ethnographies could be used to answer questions about culture, let’s go back to our earlier questions. I’ll share some speculations from eyewitnesses and historians. These are speculations because we don’t really know motivation, but we can speculate.

Question 1: Why did Magellan fight that suicidal battle?

Bergreen thinks that Magellan fought that suicidal battle because there was probably a mutiny—the third mutiny that happened on the trip. There was also the bravado of previous successes, the miraculous survival, and a miracle documented by Pigafetta: the curing of the Bendahara, the brother of Humabon.

For me, as someone who sort of lived in that world, there was certainly a mutiny. When you’re writing a novel, you can’t think of probabilities—it has to be a certainty. You have to choose a reality. The reality I chose was this: there were three ships left in Cebu, around 150 crew members left from 200-plus. Only 60 fought in that battle. That fits the number of crew members in the Trinidad, the biggest ship. Where were the rest—the 90? They were not fighting in that battle. So it was probably a mutiny. In the novel, it was certainly a mutiny.

Once I was inside the mind of Magellan, living as a knight, a true believer in Christianity and chivalry, who grew up with stories of El Cid, San Fernando, the Crusades, the Song of Roland—you could see it in his actions. This was a good bet for him. Because of the situation, many options were closed to him. He couldn’t go back to Spain—Bergreen also thinks this. His options were either to become a viceroy of this new territory, what would become the Philippines (or at least the islands of the Visayas), or die a heroic death. Fighting this battle would give him those outcomes. Either outcome is a good outcome for a medieval knight, which Magellan was.

Question 2: Why did Humabon massacre his allies?

Pigafetta thinks it was Enrique’s idea. Lav Diaz, in his recent Magellan film, believes him. There’s also an account from one of the survivors who thinks the massacre happened because they seduced the women of Cebu. Bergreen thinks that Humabon needed to repair his political relationships.

For someone who lived as Humabon in that world, I think, first of all, Humabon had to fulfill his oath of vengeance. During that time, datus had a duty to avenge the deaths of their allies and their people. The reason why people follow you—your timawa, your warriors—is because they know you will avenge their deaths. This is just how the world worked. When you have to fulfill an oath of vengeance, you wear a rattan necklace or bracelet, and you can’t remove it until you’ve fulfilled your oath.

Since Humabon and Magellan became brothers through the ritual of the blood compact (sandugo), Humabon had a duty to avenge Magellan’s death. It would be a wrong move politically to direct the vengeance toward Lapu-Lapu. What he did instead in the novel was direct that vengeance against the betrayers of Magellan—his crew members. He invited them for dinner, a farewell dinner. He promised a casket of jewelry for the king, a farewell gift for the king of Spain. There were 22 of Magellan’s crew members, including two captains. And then he massacred them, fulfilling his oath of vengeance.

There were four attempts to colonize the Philippines before the success of Miguel López de Legazpi in 1565. In one of those attempts, they found out about some survivors. They weren’t all killed—there were survivors, and they were enslaved.

Once you start thinking as a datu in that time, it makes sense. The crew of Magellan was there from April 7, and the death of Magellan happened on April 27—that’s 20 days. Magellan refused to pay tribute to Rajah Humabon. But Humabon was used to being a host, and the promise was that he would be given power by this powerful king. That was essentially the deal. He was entertaining them—150 people for 20 days was expensive. But when Magellan died, that promise came to nothing. How do you pay for that? Well, the main currency of Cebu during that time, the main thing that was traded, was actually slaves. The Spaniards paid with their bodies, essentially. That was the world during that time.

Question 3: What was the role of women in the events of 1521?

Pigafetta records his encounter with a shaman offering a pig. He records seeing this beautiful queen, the wife of Humabon. He was also entertained by some naked dancers. Those were his recollections of his time in Cebu. If you read his account, it’s pretty clear that he enjoyed his time in Cebu and was charmed by Humabon. He never speaks badly against Humabon, even though Humabon massacred his companions.

But if you know the culture during that time—and this is where I really made use of my experience growing up in a Filipino family—the women were certainly involved in those political games. For instance, the binukot, the veiled women protected from the pollution of the ground and the sun, never left their huts. They were also keepers of memory. They were like the historians during that time, but this is a different kind of history. Memory was kept through symbols and ritual.

For instance, why did the wife of Humabon (in the novel she is named Paraluman) receive the statue of the Santo Niño twice? First during her baptism, when Pigafetta gave her the statue, but then a few days later, Magellan gave her the statue again. I think that’s because the memory, the event, had to be of Magellan, the leader—he had to be the one to give it to her. That was the memory that had to be recorded through the image.

There were also ideological rivals and allies. I tried to capture that through the binukot and baylan. You see this later on in the colonial world—the suppression of the baylan. Christianity is pretty anti-sacrificial, so that was the main thing they were against. Also, they were priestesses, so they were rivals.

But there’s also the less talked about aspect: the allies, the ones who embraced Christianity and helped it spread. It’s hard to explain how a few missionaries could transform Philippine society or bring Christianity throughout the islands just by themselves. They had to have internal allies, and I think it was the women as well. If you see how parishes are run in the Philippines, you would know that women play a huge role. Nick Joaquin also talks about this in his chapter in Culture and History about the beatas. This is an understudied aspect of the acceptance of Christianity in these islands in the Philippines, similar to how the role of women is in political families, particularly in the context the Big Man.

Conclusion

We could talk more about this in the Q&A. We will be signing books after this if you’re interested.

I have a paper in development about this particular topic—historical ethnographic fiction, novel writing as fieldwork, something like that. Can novelists produce ethnographic knowledge of worlds which we could no longer access directly? This is part of a larger work, possibly about Neo-animism for Creative Work and Operating Among Psychopaths and Psychic Megafauna.3

If you want to know about that, just contact me or we can talk about it after this.

Clifford Geertz coined the term “thick description” to describe ethnographic writing that doesn’t just record observable behaviors but captures the layers of meaning, context, and cultural significance behind them—the difference between documenting that someone blinked versus understanding whether it was a conspiratorial wink, a nervous tic, or a playful gesture within that society’s symbolic system. This approach became central to interpretive anthropology, emphasizing that cultures are webs of meaning that require deep, contextualized interpretation rather than surface-level observation.

Here’s my most developed writing on this so far:

I have another theory about Humabon, Khalil, which is Netflix worthy rather than academic. Can't wait to meet you in Frankfurt to discuss. I too loved Bergreen's book, the most thrilling non fiction book I've ever read.

I was randomly just thinking about 1521 for a different reason:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diet_of_Worms