Why Sacrifice? The Other Answers.

On Cleo Kearns's Problems with René Girard’s Scapegoat Mechanism

As late as the 1960s, anthropologists have recorded ritual human sacrifice among the upland communities in the Philippines that had continued to escape modernity. For instance, on the first page of Jules de Raedt's Kalinga Sacrifice (1989), we read,

The sagang is a human sacrifice, performed for general welfare, and occasionally for the curing of the insane. Insanity is viewed as the gravest of illnesses, and the sacrifice performed for it requires a human head. Animal sacrifices are an extension of human sacrifices, and are performed in that context.

Human sacrifice is not unique to these communities. In fact, it appears to be found all over the world. The Aeneid mentions the sacrifice of slaves as part of sealing the agreement between the two warring factions in the story. Plutarch, in his Parallel Lives, describes how an omen from the liver of a sacrificial slave foretold the death of the son of King Pyrrhus of Epirus. The Torah mentions Abraham, who attempted to sacrifice his son. God's command to substitute a ram for the sacrifice is commonly interpreted as a transition from human to animal sacrifice among the ancestors of the Jews. The most well-known record of human sacrifice is probably that of the Aztecs in the 16th century. Less well-known are mentions of human sacrifice in the records of anthropologists in the early years of the discipline (20th century), when cultures yet to be touched by the West were first studied systematically and professionally (as compared to the writings of hobbyist missionaries and colonial officials). For instance, we read in Bronisław Malinowski's 1922 book Argonauts of the Western Pacific,

For woe to the canoe caught by the giant kwita! It would be held fast, unable to move for days, till the crew, dying of hunger and thirst, would decide to sacrifice one of the small boys of their number. Adorned with valuables, he would be thrown overboard, and then the kwita, satisfied, would let go its hold of the canoe, and set it free. Once a native, asked why a grown-up would not be sacrificed on such an occasion, gave me the answer: “A grown-up man would not like it; a boy has got no mind. We take him by force and throw him to the kwita.”

Why is human sacrifice found in cultures across the world? If we broaden ritual sacrifice to include non-human victims, the practice becomes a cultural universal, like song and dance. Why would all pre-modern cultures end up with the same gruesome practice along with singing and dancing?

Why even study this?

Before looking at answers to the why of sacrifice, let me explain why I'm even studying this.

When I explain my esoteric deep dives to friends and family, I usually get a look that says, "Whatever you’re talking about, I'm happy for you" (e.g., low-cost genetic sequencing) or amused and puzzled toleration (e.g., advanced notetaking techniques). When I tried to explain my explorations on sacrifice to my godmother, her facial expression was somewhere between WTF and ewww. I didn't even get to the human part.

Most of my published essays in the past year had something to do with sacrifice, particularly the "scapegoat mechanism" theory from the French-American academic René Girard. I like stretching his ideas through crossovers with other thinkers:

Girard x Venkatesh Rao's model of power dynamics in the modern office environment (this is the first of five essays)

Girard x Margaret Mead's ethnographic film Trance and Dance in Bali

I feel the need to explain why I'm spending all this time on a question that is apparently weird and gross to those beyond the academic and online communities I belong to. I realized that the "why" here is of two kinds:

Origins: how I ended up here

Purpose: the meaning of this work

This section is not a mere self-indulgent detour from the main point of this post, a look at non-Girardian answers to the why of sacrifice from Cleo Kearns (introduced below) and her problems with Girard’s theory. This same non-singular meaning of "why" will (I hope) give some clarity to where Cleo is coming from.

Okay, here's how I ended up here:

Late 2021 - Early 2022: I read Luke Burgis's Wanting, which introduced me to René Girard and his "mimetic theory." Between 2022 and 2023, I applied the model to my life. I don't think I'm exaggerating if I say mimetic theory and Luke's book were life-changing. Allow me to quote my June 2023 self:

The revelation of mimetic desire has expanded my freedom. Now that the sources of my desires are more transparent, I have greater power to direct their focus. This has been a kind of purification. For instance, I decided to end an entrepreneurial undertaking I've been working on for years (I publicly broke up with this muse), and I have said No to the shiny new objects of desire in the various tribes I belong to. Shedding these desires allowed me to focus on a few important ones. I've been more at peace, and there's probably a better chance of bringing my projects to life because of this focus.

November 2022: unveiled as pure rivalrous mimesis, my desire to build a biomanufacturing business just disappeared. So, my biology master’s no longer made sense. During a session of "mental prayer" (a kind of Christian meditation), the idea of shifting to a master’s in anthropology crossed my mind, and I literally laughed out loud! Thankfully, I was alone in the chapel. I took this as a sign from heaven, LOL. At that point, I did not know that Girard also touched on anthropology. I also didn't really know what anthropology meant at that point. However, I had a hunch that among the master’s programs available to me, anthropology would help me the most with writing my next book, Rajah Versus Conquistador. My hunch continues to be proven right.

March 2023: I enrolled in Geoff Shullenberger's René Girard course at Other Life. I was busy with other things in the first few weeks, so the first book of Girard that I went deep into was The Scapegoat (1982), the reading for one of the later weeks of the course. I eventually read it cover-to-cover, closely. It turns out the book isn't what most people who enter the world of Girard first read.

That's the origin. I'll talk about my other why at the close of this essay, because I sense it has to do with one of Cleo’s problems with Girard's ideas, and her perspective on sacrifice that I might be blind to.

Meeting Cleo Kearns

I met Cleo at a writing course at Other Life that started in May of 2023. Here's her profile. Cleo has retired as a university professor but she continues her scholarly work. She is now working on a crossover between the Old Testament and postmodernist thinkers. She posts early versions of what might become chapters of a future book at her Substack.

Cleo also continues to help novice scholars like me. For instance, she introduced me to a Girard expert when I asked for help writing my first scholarly article and publishing it in an academic journal.

What are the odds that I’d meet an expert in ritual sacrifice just as I was about to dive into this weird niche? What’s more, Cleo’s views on sacrifice are very different from Girard’s. This feels like providence. One of the biggest risks in a scholarly pursuit is getting your mind trapped in groupthink. As I've immersed myself in the world of Girard, to the point of reading articles like "Collective Violence and Birthday Parties: A Girardian Analysis of the Piñata," I'm risking blindness to the possibility that Girard might actually be wrong.

Cleo recommended the following papers after our online meeting in June 2023, when I volunteered to help her with some internet troubleshooting (I'm used to taking on this role among the elders in my family).

"Of Killer Apes and Tender Carnivores: A Shepardian Critique of Burkert and Girard on Hunting and the Evolution of Religion" by T.R. Kover

"Sacrificial pasts and messianic futures: Religion as a political prospect in René Girard and Giorgio Agamben" by Christopher A. Fox

"Inventing the Scapegoat: Theories of Sacrifice and Ritual" by Naomi Janowitz

She also mentioned that her book The Virgin Mary, Monotheism, and Sacrifice (2008) touches on Girard and other theories of sacrifice.

At that time, I felt it was too soon to end the honeymoon phase of my engagement with Girard's ideas, so I delayed reading them. I wanted to be a true believer first before possibly becoming a heretic.

It has been more than a year since the Girard course, and this month I shall complete my first year of my master’s. I have written ten essays of 3,000 - 5,000 words each related to Girard, and I'll be attempting to write my first scholarly article and get it published. Girard scholars have told me that I have correctly understood his ideas and conveyed them well. It is time to challenge Girard’s models. Cleo's recent post on her problems with Girard is another sign that the time is now.

Origin versus function versus meaning

I've been reading works that have contributed to the development of the field of anthropology as part of the master’s program (eg, Durkheim, the postmodernists). The earliest work I've read that deals with sacrifice is Henri Hubert and Marcel Mauss's Sacrifice: Its Nature and Function. At the time of its publication in 1898, scholars from the West were just beginning to notice the common elements among presumably unconnected cultures across the world. The theorizing about culture thus began.

If I'm going to specialize in ritual sacrifice, I will need to know the development of theories of sacrifice since Hubert and Mauss. Thankfully, it turns out Cleo has already done this work in the chapter entitled "Sacrifice, Gender, and Patriarchy" in her book. Cleo starts with definitions of sacrifice and then presents theories of sacrifice since the time of Hubert and Mauss.

The theories she presents remind me of an epistemological point Durkheim makes in The Rules of Sociological Method (1895). He writes,

Most sociologists believe they have accounted for phenomena once they have demonstrated the purpose they serve and the role they play. They reason as if phenomena existed solely for this role and had no determining cause save a clear or vague sense of the services they are called upon to render. This is why it is thought that all that is needful has been said to make them intelligible when it has been established that these services are real and that the social need they satisfy has been demonstrated.

[...]

But this method confuses two very different questions. To demonstrate the utility of a fact does not explain its origins, nor how it is what it is. The uses which it serves presume the specific properties characteristic of it, but do not create it. Our need for things cannot cause them to be of a particular nature; consequently, that need cannot produce them out of nothing, conferring in this way existence upon them.

This distinction has a parallel in biology. The function of an organ in an organism or a species within an ecosystem is not equivalent to its origin. Feathers in birds, for instance, function as a crucial element for flight, yet they likely evolved initially for temperature regulation or for display purposes among dinosaur ancestors.

As disciples of Durkheim, Mauss and Hubert must have been quite aware of this distinction. In the introduction of Sacrifice: Its Nature and Function, after pointing out that it is "too much to seek in an anthology of lines from the Iliad even a rough picture of primitive Greek sacrifice" and that it is "likewise impossible to hope to glean from ethnography alone the pattern of primitive institutions" because they tend to be "distorted through over-hasty observations or falsified by the exactness of our languages," Mauss and Hubert declare that,

We do not therefore propose here to trace the history and genesis of sacrifice, and if we speak of priority, we mean it in a logical and not historical sense.

Durkheim, Mauss, and Hubert were early proponents of functionalism, an approach based on the principle that cultural practices and beliefs serve to maintain and preserve the stability and continuity of the culture.

Fast-forward to contemporary anthropology, and we can see a trend toward greater consciousness of the role of "positionality" and power differences in the creation of knowledge. Perhaps this stems from recognizing the field's complicity with colonialism. Or perhaps it stems from the adoption of postmodernist underpinnings to the field's epistemologies.

Instead of theorizing about the nature of culture as the likes of Durkheim and Lévi-Strauss did around the beginning of the 20th century, a lot of anthropological work today seems to be ethnography that aims to explain a culture not from the worldview of the West, but from within that local culture's "web of meanings." Another big name in the field, Clifford Geertz, describes this approach in The Interpretation of Cultures (1973). This book popularized the term "thick description" as an ideal for ethnographies: a presentation of culture that includes not only the facts and observations but also the context, meaning, and intention behind those practices. My professor says that this is one of the most quoted parts of that book:

The concept of culture I espouse, and whose utility the essays below attempt to demonstrate, is essentially a semiotic one. Believing, with Max Weber, that man is an animal suspended in webs of significance he himself spun, I take culture to be those webs, and the analysis of it to be therefore not an experimental science in search of law but an interpretive one in search of meaning.

In multiple past essays, I described truth or knowledge as maps to the territory of reality, and epistemology as a specific map-making style. Above, we looked at three styles from the history of anthropology and sociology: explanations of origin, function, and meaning. Might Cleo have read Girard’s theory as an explanation of function or meaning, when it is actually an explanation of origin? Here's a table I made (with the help of my research assistants, Claude.ai and ChatGPT) of the theories of sacrifice she presents in the first chapter of The Virgin Mary, Monotheism, and Sacrifice. As you can see, except perhaps for Freud and Burkert's theories, the explanations presented for the phenomenon of ritual sacrifice are functionalist or semiotic, including Girard's.

"During the process of hominization"

If Cleo misunderstands Girard, she is not alone. Let me throw in this misconception by the academic and author Robin Hanson. Correcting it will help in clarifying what the scapegoat mechanism explains.

In one of his lectures, Girard uses the phrase "during the process of hominization," adding that he is speaking "as a Darwinian" in doing so, to place the origin of the scapegoat mechanism within evolutionary history. There's a paper entitled "Human Evolution and the Single Victim Mechanism: Locating Girard's Hominization Hypothesis through Literature Survey" (2017) by Chris Haw, which looks at studies from varied fields that resonate with Girard's theory. The paper has a nice distillation of Girard’s three major claims:

(A) that pre-cognitive imitation (mimesis) is a key factor driving human behavior and gives rise to numerous benefits and problems, and (B) that early human mimetic capacity coevolved with and through “the victimage mechanism”—i.e., group murder of a victim, which gave birth to the cultural order through its repetition in sacrifice, prohibitions, gods (the transcendent victim), and myth, all of which channeled and restrained violence. That is, sacrifice “domesticated” humanity, safely channeling its mimetic capacities while it outgrew its instinctual safe-guards (like dominance patterns). Finally, (C) Girard theorizes that biblical myths and their social effects, especially the gospels’ explicit representation of a founding-murder, have played a special historical role in slowly dissolving our “sacrificial safeguards” and making us capable of seeing (a bit less dimly) through our originary, opaque misapprehension.

Haw recommends Girard’s Evolution and Conversion (2007) for an explanation of the theory straight from its originator, but he provides this quote from I See Satan Fall Like Lightning (2001) in the footnote for (B) above:

“From the moment when the pre-human creature, the human-to-be, passed over a certain threshold of mimetic contagion and the animal instinct of protection against violence collapsed (the dominance patterns) mimetic conflicts must have raged among humankind, but the raging of mimetic conflict quickly produced its own antidote by giving birth to the single victim mechanism, gods, and sacrificial rituals.”

It is clear that Girard viewed the scapegoat mechanism as a (Darwinian) theory of origin rather than of function or meaning. I view it as a "collective instinct" analogous to vestigial organs, like the useless and hidden hind legs of whales.

Allow me to speculate at this crossover. A closer analog to the scapegoat mechanism are "vestigial" individual instincts that were once beneficial to humans (or pre-humans) but are possibly detrimental today: cognitive biases like confirmation bias, in-group bias, or loss aversion (Robin Hanson has a book on this). Let’s make a 2x2 using the Systems 1 and 2 model popularized by Daniel Kahneman on one axis and "individual" and "social" on the other. The scapegoat mechanism would fall under the "Collective System 1" quadrant.

Do "collective instincts" actually exist? The scholarly domain of crowd psychology seems to rest on its existence. I'm personally interested to see if the scapegoat mechanism could be a good explanation for the pogroms across history, including very recent ones like the Tutsi genocide (1994) and the massacre of Chinese-Indonesians (1998).

While the mob instinct for violence toward scapegoats is subrational, people in power can deliberately influence and use it. Girard said that scapegoating is "the ultimate craft of statesmanship." The most famous study of mass movements appears to be Eric Hoffer's The True Believer (1951), which I have yet to read. Here's the book's most famous quote: "Hatred is the most accessible and comprehensive of all unifying agents. [...] Mass movements can rise and spread without a belief in a God, but never without a belief in a devil." This is the aspect of the scapegoat mechanism I'm most interested in. When I applied for the master’s program, my proposed eventual thesis was a comparison of Philippine and Mexican nationalisms (I wanted to revisit Benedict Anderson, who blew my teenage mind). With this continuing dive into the phenomenon of sacrifice (of the Other), I'll probably end up with some sort of crossover between nationalism, power, and the scapegoat mechanism for my thesis. It will certainly appear in my book, Rajah Versus Conquistador.

Ritualization of sacrifice versus (instinctive) mob violence

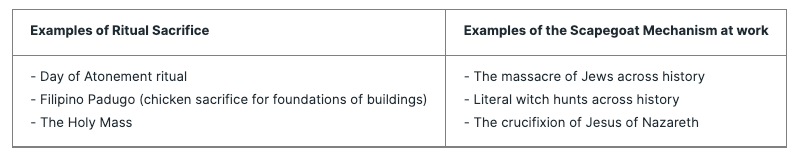

In her post, Cleo presents a Jewish ritual called the Day of Atonement and the crucifixion of Jesus of Nazareth as examples of the scapegoat mechanism. This seems to also stem from a misreading of Girard's theory. A table of examples will help clarify this.

Both ritual sacrifice and collective murder are phenomena we can observe throughout cultures and throughout history. The scapegoat mechanism is Girard's explanation for both of these phenomena, but through separate ways.

To Girard, sacrificial rituals appeared because of the power those foundational murders had on the nascent societies. Girard theorizes that the process of hominization brought with it new cognitive abilities, like a much greater capacity for mimetic desire. People’s desire for the same things eventually led to rivalry, which led to violence. The solution among non-humans, according to Girard, is a stable dominance hierarchy. Since humans lost this option with greater cognitive abilities, other solutions had to arise. This solution, according to Girard, had to be earlier and more mechanical than the primordial social contract. This solution was the mob instinct of laying the blame on an individual or subgroup and their eventual murder. This situation of chaos and its violent resolution happened again and again throughout the hidden past of humanity. This repeated restoration of peace felt magical and important to the murdering crowd, that it eventually became ritualized. Stories about this foundational murder were passed down in the form of myths. To Girard, the magical effectiveness of this murder is the reason why sacrifice is related to the sense of the sacred.

This repeated existential threat and its bloody resolution not only produced sacrificial rituals and myths. It is also the source of the mob instinct that continues to live within us, lying dormant until it is awakened by chaos. This instinct is the Girardian explanation for the mob's common reaction to Jews in Medieval Europe, witches in pre-modern New England, Tutsis in Rwanda, and Jesus of Nazareth.

Cleo's other problems with Girard

Cleo also critiques Girard's interpretation of biblical and anthropological sources. I have near zero knowledge and professional training in these domains, so I can't say anything here. Except:

Girard's method seems consistent with what Claude Lévi-Strauss proposed in the chapter "The Structural Study of Myth" in his 1958 book Structural Anthropology. Like Lévi-Strauss, Girard assumes that texts are distorted as they are passed across millennia orally or in writing. However, if you compare many of these distorted texts, you could see a pattern that tells you... something. To Lévi-Strauss, this something was the underlying structure of the myth itself, revealing universal patterns of human thought. Other scholars found other things. To Carl Jung, the pattern of myths revealed the "collective unconscious" and archetypal figures such as the Hero, the Mother, and the Trickster. Joseph Campbell saw a common narrative structure across these texts: the "hero's journey."

Unsurprisingly, Girard saw the scapegoat mechanism in these texts. He presents several examples in The Scapegoat. My (untrained) eyebrows were raised countless times as I read his daring speculations of what the distorted texts meant. His samples are what he calls "persecution texts." Again, these tend to be passed on and ritualized because they tell of the foundation of societies: that the solution to its near destruction is the sacrifice of a person or a subgroup.

I come from a science and engineering background, so Girard’s map-making method challenged my preconceptions of valid pathways to truth. So I was surprised when I applied Girard's model to Margaret Mead's documentation of a Balinese myth expressed in dance: it fit so well! I still don't know what to make of this. Maybe it is true?

Cleo also questions Girard's claim that Christianity unveiled the scapegoat mechanism and thus made it less effective (the third point (C) in the quote from the Chris Haw paper above). Girard does not claim that the instinct for collective murder disappeared after the crucifixion of Jesus. This unveiling is Girard's explanation of the difference between the moral worldview of modernity (e.g., equality of all men and women and siding with the downtrodden) versus the moral worldview before and outside it. In one of his lectures, Girard was asked about the phenomenon today of people claiming victim status. Girard replies, "This is absolutely unique. If someone had come to Pilate, for instance, and claimed victim status, or someone had gone to a Chinese official, and said, 'I am a victim, therefore I have rights,' they would have been laughed out of court." This is the same thesis that strings together the history that Tom Holland presents in Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World (2019). I'm seeing this same difference when comparing Philippine folk literature before and after Christianization, particularly in the understanding of sacrifice: vernacular words, like the Kalinga sagang, tend to mean sacrifice of others, while sacrificio, adopted from the thoroughly Christianized Spanish, tends to mean self-sacrifice.

Girard's anthropology is "near-Calvinist, highly masculinist, and capitalist-inflected" (my other why)

After I read Liz Gilbert’s Big Magic back in 2018, I immediately made it my operating system for creative work. This means that I don’t make career choices or scholarly pursuits based on some sort of rationalization, like economic trends or institutional strategy. My guide has been the ideas themselves. I follow those that speak to me, both directly and through the serendipities they send my way (like my connection with Cleo).

As seen in most of the posts on this site, Girard’s theory spoke to me. Why? The answer might be related to this part of Cleo’s post that struck me:

The anthropology of the human he seems to presuppose here evinces a near-Calvinist, highly masculinist, and capitalist-inflected view of humans as fundamentally and by nature in a barbaric state of rabid envy, negative projection, and violent competition that must be repeatedly mediated by a fragile civilizing function.

This struck me because a few months ago, a friend who teaches literature challenged me to write an essay that follows the form of a couple of examples he sent me. They were "personal" essays. I tried to out-navel-gaze them, and the result was Threads: On Filial Love, Cringe, and Mild Sociopathy.

One unintended result of the work of introspection needed for that essay was unveiling three specters that framed my view of the world. Just as Flannery O'Connor noticed how the American South was "Christ-haunted," I realized through writing that essay that I am haunted by the specters of the Austronesian Big Man, Technocapital, and Filipino Machismo. These sound a lot like the invisible villains that Cleo points out to be behind Girard's theory.

Exorcists need to know the names of the demons they wish to expunge. I don't consider these three specters to be demons. In fact, I am thankful to them for helping me operate in this world. Yet, they could be terrible masters to those they possess, and unveiling them is the first step to ensuring my freedom.

Staring them straight in the eye, as I do when I study these specters, carries the risk that they stare right back at me. This could lead to a possession more complete than the unconscious kind.

I read the first chapter of Cleo's The Virgin Mary, Monotheism, and Sacrifice so that I could write this post. I will read the rest of the book with devotion. I sense that she offers a perspective of sacrifice unavailable to me, given my specters. The many mothers in my life have pulled me out of ditches that I dug myself into several times in the past. Perhaps I'm digging a scholarly ditch right now, and mama will have to save me again.

Fascinating stuff. Regarding Philippine Folk literature, Damiana Eugenio's Philippine folk literature series is a solid resource.

So honored by this level of engagement with my work and more importantly that of the masters! I hope to respond in depth soon but just here wanting to express deep gratitude, great interest and great respect for your process. I think that my fundamental existential concern here is for the value of sacrifice as essential to personal and collective life. That said, my monotheism and sacrifice book is far behind my current perspective and I am tempted to a major revision. If I do that it will be with your work in mind and cited! .