The Departed (2006): Sociopaths Versus Normies Versus Clueless Truth-Seekers

Using The Philosopher-Citizen-King Triangle For Fiction

The Triangulations series (I, II, III) crossed over René Girard’s scapegoat mechanism with Venkatesh Rao’s model of power dynamics of the modern office. The result was an update to Rao’s triangle. This new model says that people tend to create knowledge through three styles or epistemologies—harmony, power, or truth—and operate within society through one of these lenses. We exposed the Nietzschean bias of Rao’s archetypes of “Clueless,” “Losers,” and “Sociopaths” and replaced them with “Philosopher,” “Citizen,” and “King.”

Scientific models are updated when new ones better fit the data, improve predictions, and translate into real-world applications through technology. Models of human behavior are validated more through their explanatory power and are applied as better ways to live among people.1

In an epilogue to Triangulations, I applied this model to understand why the Philippines—including some friends—chose the son of the dictator, Ferdinand Marcos, as the new president. It produced a more satisfying explanation than the widespread theory that blamed “misinformation” for the Marcoses’ return to power.

I’d like to create a second epilogue for a more global interest. I'll apply the three epistemologies, and their implications theorized in Triangulations, to Martin Scorsese’s 2006 Oscar-winning film, The Departed. After introducing the main characters through the lens of our triangle, I’ll also explore the following:

How sociopaths are made

The rock-paper-scissors dynamic among the pathologies of the three epistemologies

How to be a good king

Needless to say, spoilers ahead!

1/4 Our Clueless Hero, the Lying Normie, and the Sociopathic Player

The Departed opens by introducing its villains. We first meet Colin Sullivan as a kid. We see him as an altar boy serving in a well-lit church juxtaposed with scenes of him in a dark garage listening to a monologue by Frank Costello, the psychopathic drug lord played by Jack Nicholson. Costello grooms Sullivan to be one of his foot soldiers. He tells the boy, “A man makes his own way. No one gives it to you. You have to take it. Non serviam.” The church scene tells us that the film is using a Christian lens, and Costello’s “non serviam” suggests that he is a Satan figure.

In the same sequence, we see Costello carry out an execution on a beach. He shoots a kneeling, hogtied woman behind the head. He then observes, like a connoisseur, “Jeez... she fell funny.” Even his axe- and saw-wielding henchman finds this disturbing. He tells his boss, “Frank, you should really see somebody.”

Costello clearly falls under the epistemology of power in our triangle. The character also fits the extreme pathological manifestation of this corner. In Part II of Triangulations, we theorized that the pathologies of each corner stem from the absence of the two other corners. In Costello’s case, we see the absence of truth (he turns out to be the film’s biggest rat) and the disregard for harmony (murder, betrayal, and breaking all sorts of religious and sexual taboos).

We then see Colin Sullivan all grown up, played by Matt Damon. He enters the police academy. Our hero, William “Billy” Costigan Jr., played by Leonardo DiCaprio, is introduced in the same setting, but their lives don’t intersect at this point. They brush by each other in a key scene after their graduation, where they are welcomed into the police force. We see contrasting playbooks, reflected by how those in power deal with them.

Bad cop Sullivan goes in first. The scene is short. The senior officers welcome him with some Boston slang. He receives some words of encouragement, and he exits with a smug expression on his face.

Good cop Costigan goes in next. In contrast to the previous scene, this one is long and tense. The officers put our hero in his place, reminding him of all the petty and failed criminals in his family. At the same time, he receives some backhanded compliments. We get to know about his high SAT scores, his good education, and his ability to blend into wealthy neighborhoods and the tough streets of South Boston. The message of the senior officers is that he’s the perfect guy for the undercover job they are offering him, but also that he also has no “fucking” choice if he wants to be a cop.

In a flashback, the good cop’s uncle tells him, "You always have to question everything don’t ya?" and he replies with some harsh truths about the uncle and his wife. We see that Costigan is a righteous and fearlessly honest man. His senior officers weaponize this righteousness with his undercover assignment. The bad cop mirrors the good cop by working as the drug lord's inside man in the police force. The hardships that the good cop faces as he infiltrates the drug lord's organization are also reflected and inverted by the bad cop. He deftly plays office politics, gets promotions, and lives in luxury, secretly funded by the drug lord.

In these opening scenes, we see the bad cop’s desire to rise in society. This leads him to buy an expensive condo unit, paid for by his patron. In the elevator to his unit, he meets a psychiatrist, played by Vera Farmiga. They date. We see that she has a good heart.

The psychiatrist provides her services to people on parole. The good cop’s cover is that he was kicked out of the academy because of a crime; he is assigned to see the psychiatrist. In one of their sessions, the good cop asks her if she lies. She tries to evade the question, but the good cop pushes her to admit so. He asks why. She replies, "To keep things on an even keel."

So the triangle is complete, with each corner exhibiting its unique pathology:

a truth-seeker clueless at being a pawn of power players

a sociopath leaving dead bodies along his rise to power

a normie who lies to keep the peace

The film’s dramatic tension relies on how the good cop, the bad cop, and the rest of the characters attempt to find the other side’s mole. In addition, the psychiatrist moves in with her boyfriend, the bad cop, but then cheats on him with the good cop.

Now that we have mapped the film’s main characters onto our triangle, let’s see how the implications of our model, as we saw in Parts II and III of Triangulations, fit the film’s story as it unfolds. Here’s a diagram that maps out other characters in our triangle and the three fronts I’d like to explore.

2/4 How sociopaths are made

In Rao’s model, Sociopaths are recruited from “Losers,” those who recognize the Sociopath’s game but can’t play it. Again, this is a perspective skewed through the lens of power. “Citizens” simply desire peace and harmony and see the world through this lens. Their first step toward sociopathy is to sacrifice truth for the sake of peace. The next step is to sacrifice lives for the sake of peace. This was the ancient solution to the emergent dangers of a species with episodic memory, which Girard identified as the scapegoat mechanism. The final step to sociopathy is to utilize sacrifice for the sake of power.

We see this in the bad cop’s satanic descent. When the good captain, played by Martin Sheen, is killed, the bad cop turns him into a scapegoat by suggesting that the captain is the mole. Later in the film, he also kills his sponsor, the drug lord, to protect himself. In the unexpected climax of the film, he kills and scapegoats the colleague who saves his life.

The fully actualized psychopath, the drug lord, says in a scene with the good cop, “A lot of people had to die for me to be me.” In Part II of Triangulations, I mention Girard’s observation that scapegoating is the “ultimate craft of statesmanship.”2 This leads to the conjecture that psychopaths use this mechanism to gain power. The film’s depiction of the bad cop and the drug lord supports this observation.

This may be a kind of honest and costly signaling. Brian Klaas's Corruptible, a book about sociopaths and power, presents a theory on the evolutionary origins of sociopathy, or dominating violent behavior (Chapter 2). These behaviors were already present among pre-human apes in the figure of the alpha male, which is a high-risk, high-reward reproduction strategy. If you vie for the top spot, you expose yourself to dangers from rivals and mutinous followers. But if you get it, you have a near monopoly on the females.

The invention of ranged weapons (e.g., spears) increased the risk side of this equation, resulting in the egalitarian structure of hunter-gatherer tribes. We can still see this in the cultures of premodern tribes today.

This was reversed with the invention of agriculture. When survival is based on protecting territory, better-organized communities tend to defeat less-organized ones (big army vs. small army). The figure of the king, therefore, returned. A strong and high center allowed the creation of bigger and stronger communities.

To support this structure, the king lays down the law. At the same time, breaking the law is a costly and honest signal of how far you are willing to go to gain and maintain power. You are telling the tribe that you are the bad man that can protect them from the other tribe’s bad man, and the bad man you don’t mess with. We read in Marshal Sahlins’s and David Graeber’s On Kings, an anthropology of kingship across cultures,

On his way to the kingdom, the dynastic founder is notorious for exploits of incest, fratricide, patricide, or other crimes against kinship and common morality; he may also be famous for defeating dangerous natural or human foes. The hero manifests a nature above, beyond, and greater than the people he is destined to rule hence his power to do so.

Okay, enough of evil kings. As mentioned above, my goal in theorizing—i.e., building better models of reality—is to live a better life. Identifying bad kings and exposing the source of their power is a weapon of defense, like a shield. I’m more interested, however, with weapons of offense. How does one find good kings or live as one? I’ll present some answers to this question in the last section, but before that, let’s quickly look at another triangle and map it to the film.

3/4 The rock-paper-scissors dynamic among the pathologies of the three epistemologies

Internet memes are also models of reality. Their spread could indicate people’s agreement with the map’s correspondence to the territory. This diagram, which we already saw in Part II of Triangulations, has been circulating in certain corners of the internet for years. The rock-paper-scissors dynamic among the three archetypes it presents fits quite well with The Departed.

“Normies” in this diagram map to our epistemology of harmony. Aside from the psychiatrist, the film has a couple of other normies. For instance, at the movie’s climax, the good cop is killed by a colleague who turns out to also work for the drug lord. He tells the bad cop, “It’s you and me now, you understand? We got to take care of each other, you understand?”

The bad cop, as soon as he gets the chance, shoots and kills this normie cop who just saved his life. This murder transforms the normie cop into a scapegoat, freeing the bad cop from suspicion as the drug lord’s mole in the police.

This scene shows a misconception of the Normie-Psychopath-Autist triangle above. It labels Normies and Autists as “moral.” It is more accurate to say that each side develops a morality through their lenses. To the normie cop, the “right” thing to do is to kill the good cop for the sake of harmony with the bad cop. The “right” thing for the bad cop is the normie cop’s death. Another normie is the goon who found out that Costigan was the undercover cop. His last words expressed his morality. He never rats. Contrast this to the drug lord, the film’s biggest rat. Normies are keepers of taboo. They keep society on an even keel.

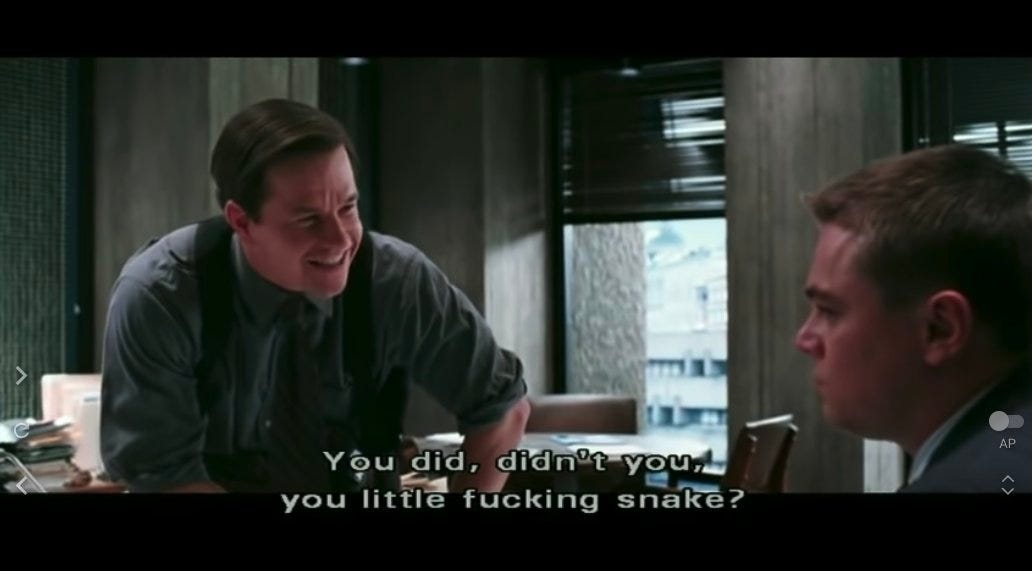

To complete the cycle, the captain’s fiercely loyal and foul-mouthed sidekick, Sgt. Sean Dignam (played by Mark Wahlberg), kills the bad cop at the film's ending. In the diagram above with the three overlapping circles, I place Dignam in the intersection between the epistemologies of truth and power, and he points to some interesting answers to our question in the next section.

4/4 How to be a good king

The Departed depicts two parallel kingships (or fatherhoods). The drug lord rules by fear: he threatens the bad cop using the girlfriend. The captain appeals to a sort of filial love: “Hang tight for me, kid,” he says in this scene.

As seen in the intro, the film uses a Christian lens. Using this lens, we can see a stark difference between the sacrifices of two father figures. The drug lord sacrifices everyone around him for his own sake, while the captain sacrifices himself for the sake of the good cop.

The presence of human sacrifice in most, if not all, premodern societies is an uncomfortable truth in anthropology (no academic in my country dares to talk about how this was still happening as late as the ‘60s). Girard explains this cultural universal through the scapegoat mechanism. The collective murder of an individual or subgroup unites the rest of the community and restores peace in their society. To Girard, Judeo-Christian scripture unveiled this lie. Pre-Christian kings utilized the scapegoat mechanism, or they themselves could fall victim to it (e.g., Girard’s reading of the Oedipus myth). Christian power players have Christ, “the King,” as their model.

Given the film’s Christian lens, I see the good captain as a Christ figure. When he realizes that Costigan might be put in danger by being seen with him, he acts as a decoy to allow the good cop to escape. He makes the sign of the cross just before facing his executioners. When they emerge from the elevator, he casually asks them, “Got a light, boys?” We then see him thrown off the building to his death.

There’s an ancient description of Christ as “Priest, Prophet, and King.” The diagram below uses this trio and presents the idea mentioned in Part II of Triangulations and repeated above. Christ is perfect because he is all three archetypes. Following Christ defectively results in the pathologies reflected in Rao’s model. The good captain is Christ-like as king (he holds power), prophet (he is on the side of truth, in contrast to the drug lord), and priest (he sacrifices himself for others, which the drug lord darkly mirrors).

Interestingly, the film’s actual protagonist is powerless. The good cop is a slave to his circumstances, a pawn in power games beyond his view, and is killed almost like an extra. The sacrifice of his death does not result in justice or victory for the good side.

Sgt. Dignam brings the film to a satisfying Hollywood ending. The good guys win in the end, but their victory is won by breaking a major taboo: thou shalt not kill. Or, in the moral code of modernity, don’t kill extrajudicially.

Among the questions we explored above, “How to be a good king” is the one I’m most interested in. However, I’m not yet satisfied with the answers in this section. So, in a future post, I’ll explore it further:

Why many fictional heroes today tend to be blind to the game of power like the good cop

How Sgt. Dignam points to a forgotten Christian playbook for wielding power

How I plan to use this playbook in my life

I largely agree with Neil Postman that social science is akin to moral theology, but I also see these models of human and societal behavior as maps that truly represent the territory of reality (e.g., Girard’s theories as Deutschean "good explanations").

Girard says it in a lecture https://twitter.com/kcorazo/status/1664468437610147842

Great questions here. Regarding the question of why heroes are blind, I think it has something to do with the concept of the sacred. The sacred is like a veil that prevents us from looking at certain taboo things, and power is one thing that can be considered sacred. If you examine it too closely it can corrupt you, so we agree to pursue status in a veiled way.

Even philosophers must agree to this veil. They pursue ‘truth’ when on some level it’s obvious that pursuit of truth is a status game. If you admit that you are just saying clever things for sex or money you are booted from the club. You have to love truth and any success that comes is secondary.

This veil serves the important social function of allowing men to compete in a way that is more likely to be socially benign. If we suspect someone is looking behind the veil we can’t really trust them because we will always suspect that they don’t really love the truth (or the common good, or football or whatever game they are playing).

A hero must respect the sacred or they become a threat to social cohesion. In fact, you could argue that giving men socially acceptable models of ambition is a primary function of hero narratives. Without the sacred, the competition becomes too brutal and civilization breaks down.