Triangulations II: Across a Galaxy of Triangles

To Boldly Cross Where No One Has Crossed Over Before

How do we know truth? I'm not talking about the truth, but just plain everyday true things that come from our voices or keyboards.

"Truth is a map of the territory of reality" is a metaphor I've repeatedly used in past essays. As a writer, I like this because it allows me to avoid the jargon "epistemology." Instead, I can use "map-making style" to mean one's way of creating knowledge. For instance, here's how we can describe some dominant epistemologies:

Classical: the map is true because it represents the territory ("correspondence")

Science: the map is reliable because it was made with replicable measurements of the territory

Postmodernist: but the map was made by those in power and thus tainted by their "positionality"

Critical Theories: we must remake the map for the oppressed ✊🏽

David Deutsch's The Beginning of Infinity, which I'm currently reading, is mainly about the epistemology of science. In fact, to Deutsch, science is the only true epistemology. Whether or not this is true, it is a useful guide for making maps of reality.

Deutsch also says that scientific maps are first drafted and then corrected or discarded by measurements of the territory of reality. We start with conjectures and then falsify them with experiments and observation. Thus, scientific truth is never completely certain. He calls this "fallibilism." In other words, the map is not the territory but only a representation of it, and it can always be improved by better measurements of reality.

1. Conjecture-Maxxing

In Part I of Triangulations, we combined two maps of social reality: René Girard's scapegoat mechanism and Venkatesh Rao's Gervais Principle. In the masterplan of this current season of Explorations.ph, I said that our eventual destination is to use these maps to view Philippine culture and history through new lenses. What I didn't mention is an even deeper motivation for my writing: I want to live a better life, and I believe that having better maps of reality helps me do that.

So, in this second part, I want to expand and add more detail to our draft. We’ll do this by riffing on the triangle we made, one of Rao's triangles from The Gervais Principle, and other similar triangles. Like Part I, this will be a hero's journey, but more of Star Trek meets Dante's Divine Comedy. We’ll start our journey on infernal planets and then proceed to more heavenly ones. When we return home in Part III, we will have learned enough from our journey to create playbooks for scholarship and for life.

We’ll go straight to the planets, without introductions or overviews, so your experience can approximate mine when I first did these crossovers.

Let's roll.

2. Philosopher-Citizen-King

We ended Part I with this triangle and a promise to dive into it. Let’s do that now.

This triangle retains Rao's original trio of Sociopath, Loser, and Clueless. By way of Girard's critique of Nietzsche, we exposed the epistemic distortion of Rao's original triangle. It was created through a Nietzchean epistemology, which assumes that the game of life is about power, all the way down. We are correcting this distortion by viewing the world through the eyes of each archetype.

"Citizens" create maps of reality based on avoiding conflict. This is the ancient map that allowed our species to survive the inevitable crises that come with our cognitive abilities, like episodic memory and mimetic desire. As we laid out in Part I, Girard's "scapegoat mechanism" was the evolutionary solution to these crises. This is Girard's explanation of why ritual sacrifice is found in all archaic societies. In the jargon of anthropology, sacrifice is a "cultural universal."

Citizens keep the peace by enforcing taboos and continuing traditions (e.g., the cultural universal of sacred rituals). Their pathological mirror image is the mob that purchases peace through the sacrifice of a scapegoat, a murder concealed with lies. If you were ever ostracized for being different, this is probably the evolutionary origin of that tendency.

We inherited the power structure of our pre-human ancestors with the alpha male at the apex of a tribe. I used the gendered label "King" because of the maleness of this archetype, but its application, as we will see in Part III, could be useful to both men and women. Taboos are another cultural universal, and breaking them is one path to kingship. Salhin's and Graeber's 2017 book On Kings provides examples of taboo-breaking kings, but if you have ever worked with sociopaths, you'd know what I mean.

Evil kings grab power through sociopathy. Good kings are crowned by their tribe through exemplary manhood. I find The Art of Manliness's The 3 P's of Manhood to be a good map of what good kingship means: Protect, Procreate, and Provide. Even among non-human primates, there is a range of approaches to leadership. The primatologist Frans de Waal, whom we met in Part I, explains in his TED Talk how a chimp with strong positive relationships with his troop can beat a stronger bully for the alpha position.

In Part I, we saw Girard's history of these three epistemologies. The epistemologies of harmony and of power dominated most of human evolutionary history. Judeo-Christian revelation jammed the scapegoat mechanism by unveiling the innocence of the victim. This has upturned the tendency to side with the strong and to create knowledge from their perspective. Today, our core value is to side with the weak, which has ushered in the Age of Truth. In his book, Deutsch wonders why Athens did not spread as "The West" did. It’s plain to see why after Girard's exposition: to the Athenians, slavery was as natural as gravity. The equal dignity of all men and women is the foundation of the Age of Truth and the beginning of infinity.

I look forward to applying this model to my scholarly work. I'll retell the encounter between the pagan king Humabon and the Christian conquistador Ferdinand Magellan through the lens of this triangle. Previously baffling events in Pigafetta's account of Magellan's voyage, like the massacre of his crew by their supposed ally Humabon, will make a lot of sense through Girard's and Rao's maps. I'm also looking forward to applying the same treatment to the game between the brilliant power player Marcos and the martyr Ninoy.

On to the next planet.

3. Rao's Lifecycle of a Firm

Rao presents several diagrams in his series, most of which resonated with my own experience. Let's examine one that doesn't. The diagram below shows Rao's lifecycle of a firm, which rhymes with the broad history of humanity we outlined in Part I. To quote Rao:

A Sociopath with an idea recruits just enough Losers to kick off the cycle. As it grows it requires a Clueless layer to turn it into a controlled reaction rather than a runaway explosion. Eventually, as value hits diminishing returns, both the Sociopaths and Losers make their exits, and the Clueless start to dominate. Finally, the hollow brittle shell collapses on itself and anything of value is recycled by the sociopaths according to meta-firm logic.

In Part IV of The Gervais Principle, Rao talks about the humor of the three archetypes. Both "Clueless humor" and "Loser humor" aim to produce laughter from others, producing a sort of social currency. "Sociopath humor," however, is meant for the enjoyment of the Sociopath himself, and everyone else is the butt of the joke.

It can only happen when the jokester and audience are the same person (which replaces social proof with individual judgment), and everybody else present is a victim, often unaware that they are being made fun of.

We cannot discount the possibility that Rao is a sociopathic philosopher (Nietzsche was, as we will see in Part III) and that the diagram above, or even the entirety of The Gervais Principle, is a joke at the expense of its readers. Rao's lifecycle of a firm, for instance, is so different from my experience in corporate tech and entrepreneurship.

Have you ever noticed that while there's postmodern philosophy, anthropology, and even theology, there is no postmodern biology, plumbing, or entrepreneurship? That's because if you're part of the latter group, reality punches you in the face every damn day.

Like the genomes mentioned in Part I and the prelude to this series, viable business models are records of truth. In a free market, you only make money if you create something customers want to pay for (expressed by revenue) in an efficient way (expressed by profit).

Okay, perhaps there is such a thing as postmodern entrepreneurship or perhaps Nietzschean entrepreneurship. A lot of rich families in the Philippines and all over the world got their money through "rent-seeking." Academics are terrible at naming. This should have been named "monetization of power." This ranges from unfair access to projects due to political connections all the way to kickbacks. Those who make money through power look like entrepreneurs from the outside, but could not be more different where it matters. Real entrepreneurs make money by creating value. They increase the wealth circulating in the world. They’re like the plants and animals in a vibrant ecosystem. On the other hand, rent-seekers are like parasites who grow by bleeding the life out of their hosts.

The two Fortune 50 corporations I worked in both hand out rewards based on merit. They continue to thrive because of the virtuous cycle of one's good work, resulting in value for customers. This value returns in the form of promotions, recognition, and salary increases. Because of their reward structures, even sociopaths are forced to play the game of creating value in exchange for power. I've tried to recreate this virtuous cycle in the small business I started a decade ago and which I continue to run up to now. As "king," my role is to establish the law (e.g., clear rules for rewards and recognition) and to enforce them fairly.

There are people whose calling is to play the game of power. Most of us, however, are kings and queens in small domains: we head families, teams, or volunteer organizations. I want to know how a good sovereign operates in the modern world. How do you establish, grow, and protect your sovereignty? How do you deal with other sovereigns, both good and bad ones? What's the playbook of a good king or queen? Can we build it by inverting slightly sociopathic playbooks like Robert Greene's The 48 Laws of Power? This would be an interesting future exploration.

Let's move on to the next planet.

4. Normie, Psychopath, Autist

I got this diagram from Rival Voices's Glossary. This most likely evolved from Rao's triangle through the anonymous horde at 4Chan or Reddit. This triangle shows us the strengths and weaknesses of each archetype in relation to one another.

Before the Age of Truth, there were no autists to limit the power of psychopaths. The most successful ones created monopolies of procreation. In The Red Queen (2003), Matt Ridley tells us how emperors from six different ancient civilizations developed the same techniques to keep women to themselves (e.g., guarding them with castrated men).

Without exception, that vast accumulation of power was always translated into prodigious sexual productivity. The Babylonian king Hammurabi had thousands of slave "wives" at his command. The Egyptian pharaoh Akhenaten procured 317 concubines and "droves" of consorts. The Aztec ruler Montezuma enjoyed 4,000 concubines. The Indian emperor Udayama preserved sixteen thousand consorts in apartments ringed by fire and guarded by eunuchs. The Chinese emperor Fei-ti had ten thousand women in his harem. The Inca Atahualpa, as we have seen, kept virgins on tap throughout the kingdom.

Where does this power come from? One kingly attribute that I have not seen explored is their ability to work with "spirits," probably because this sounds like superstition from the epistemology of truth. Girard opened an angle that might be more acceptable to this age. To him, the biblical satan symbolizes the scapegoat mechanism, and power players since the foundation of the world have worked with this demonic spirit to conquer and rule.

According to Girard, scapegoating, or collaborating with satan, is the ultimate act of statesmanship. Caiaphas knew of this power: "It is expedient for us, that one man should die for the people, and that the whole nation perish not." Pilate also knew: he let an innocent man be crucified rather than risk a rebellion. Modern political operators know this, with their campaigns based on hatred for a common enemy. Jesus knew this but rejected satan's offer:

In archaic times, satan was the only demon. With the age of language and, later on, literacy, autists have helped create a multitude of specters haunting humanity.

Extremely online rationalists have seen these demons. See, for instance, Scott Alexander's Meditations on Moloch and Kevin Simler's Neurons Gone Wild. In the "post-rationalist" corner of the internet, where Rao is part of the canon, these emergent forces are called "egregores" or "psychofauna."

Autists give birth to psychofauna with their words, normies nurture them with their belief, and psychopaths ride them to heights of power. The most powerful egregores are still variations of satan. The leaders in recent centuries have reached the pinnacle of the kingdoms of this world by working with these spirits. Psychopaths gain power by sacrificing lives, both innocent and guilty, to demons created by the collective thought forms of normies.

If we step outside the epistemology of truth, we can imagine how gods might have been formed in ancient times. To assume that gods were explanations of physical phenomena is such a science-autist view. If we create knowledge for survival and for domination, anthropomorphizing (or demonifying) these forces have a lot of functional sense. We sort of do the same today. Money, nations, and rights have no existence outside of our collective imagination, but our world cannot function without them. Even for truth-seeking, assigning motivation and agency to these emergent forces has some advantages. For instance, our minds tend to be better at working with persons much more than abstractions, as I elaborated in a previous post.

Girard says that Christ's revelation killed all the ancient gods. In this sense, the Romans were accurate in their condemnation of the early Christians for "atheism." God becoming man and dying for humanity means that we are greater than egregores, psychofaunas, and demons. The principalities and powers of this world have been exposed to be mere cognitive exhaust from humanity. But they are still powerful. And psychopaths still use them.

I used the notion of egregores to make sense of the last Philippine elections, when the son of the dictator Ferdinand Marcos was elected as president. My gut tells me that the same angle will also make sense with the rise of power players along with the rise of nationalism, which is perhaps modernity's greatest egregore. Nationalism and other modern egregores are descendants of Moloch because they thrive with the sacrifice of scapegoats. The decrepit Spanish Empire was the scapegoat of the American colonial regime in the Philippines. The oligarchy, the communists, and Ninoy were scapegoats of the Marcos presidency. Marcos was the scapegoat of the Cory Aquino administration. Drug addicts were the scapegoats of Duterte.

David Chapman's "Geeks, MOPs, and sociopaths in subculture evolution," which is based on Rao's triangle, would also be an interesting lens through which to view the birth and growth of the nation.

During the Spanish colonial era of the Philippines, there were pogroms targeting the minority Chinese merchants and craftsmen, which mirrored the massacres of Jews in Medieval Europe. It will be interesting to compare them, particularly the distortions and lies in the accounts of the perpetrators that Girard points out in his book The Scapegoat.

5. Friendly Ambitious Nerd

Let's get out of these infernal planets and visit positive versions of the △. The most internet-famous is probably visakan veerasamy's "Friendly Ambitious Nerd." Through it, we can see that the pathologies of each archetype can be inverted into a virtue:

In Girardian terms, ambitious Kings establish societies and create law and culture (Romulus, Cain). The friendship among Citizens keeps society together (the keepers of taboo and ritual). Nerdy Philosophers expand society (to infinity, for Deutsch) with the antifragility of truth (this is explained in Part I).

Visa has a book entitled Friendly Ambitious Nerd, which has been on my digital shelf for a long time. Perhaps now is the time to read it and to add more details to our conjectures.

As I was writing this essay, I found out that Visa created F.A.N. based on Rao's triangle. That means all the triangles above probably stem from Rao's. However, a similar triangle has existed in Christology for centuries past.

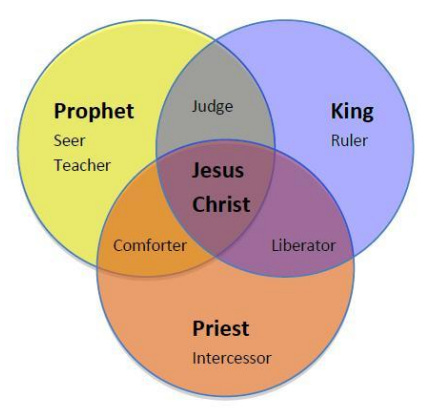

6. Christ: Priest, Prophet, and King

Christ is:

Priest: point of unity

Prophet: speaker of truth

King: keeper of law and order

This means that to be satanic is to be:

a mob united in murder

a liar

someone who gains power through sacrifice at Moloch's altar

We also see in this model that the absence of the virtues of the other archetypes is the source of the pathology of each.

Sociopaths are Kings without love and truth

Losers are Citizens without power and truth

The Clueless are Philosophers without love and power

This Christological △ shows us that the corners are not individuals but parts of individuals, and that the stunting of a corner results in the corruption of the others. This is perhaps the most important point in using this model to grow in virtue. We will dive deeper into this in Part III.

7. Two Other Planets

We have harvested enough conjectures from this journey to create practical guides in Part III and try them out in real life. So, I will leave two other planets for future intergalactic tours. Let's take a quick peek, though. They show us how variations of our △ can be seen across a diversity of domains.

One is the TLP (Truth, Love, Power) △ from Steve Pavlina's Personal Development for Smart People (2009), a self-help book (h/t Mesh Thomas). I'm curious to find out which observations led Pavlina to this triangle.

Balaji Srinivasan's △ in his book The Network State predicts the powers that will define the near future of worldwide society. My slight familiarity with Balaji tells me that, to him, the New York Times is pathological harmony, and the Chinese Communist Party is pathological power. Balaji seems to be a Bitcoin maximalist, or at least partisan, so I'm not sure if he sees anything pathological with the truth of a public ledger whose veracity is protected by cryptography.

8. Following Girard's Map-Making Approach (Let's Bring This Home)

In his 2021 book Wanting, Luke Burgis relays how Girard saw a curious pattern in great works of literature, which led to his mimetic theory, a map of reality that had a huge impact on my life (I wrote about this impact in The Three-City Problem of Meaningless Work).

[Girard] uncovered something perplexing, something which seemed to be present in nearly all of the most compelling novels ever written: characters in these novels rely on other characters to show them what is worth wanting. They don't spontaneously desire anything. Instead, their desires are formed by interacting with other characters who alter their goals and their behavior—most of all, their desires.

Girard's scholarly approach inspired the crossovers in this second part of the Triangulations series. If Girard can extract truths about human nature from the works of humanity's great observers—novelists—perhaps we can also discover some truths from Rao's △ and variations of it.

Coming from a science and engineering background, I initially felt uneasy with how Girard created his maps of reality, despite how useful his mimetic theory was in my life. My rudimentary background in epistemology was limited to "falsifiability," Karl Popper's demarcation between science and non-science. I followed the Popper trail and ended up reading David Deutsch's The Beginning of Infinity, which improves and expands Popper's ideas.

I'm still in the middle of the book as of this writing, but Deutsch's criteria for "Good Explanations" offer a way to compare maps of reality. Using it, we can ask which one better represents the territory, rather than just judging whether an idea is scientific or not.

In Part I of Triangulations, we saw Girard's scapegoat mechanism explain the cultural universals of ritual sacrifice and the sacred, why The Age of Truth (or "The West") has spread all over the world and how it came to be, the philosophical underpinnings of militant postmodernism, and how Rao's △ is rooted in human nature. In this current essay, we differentiated good and bad kingship, and true entrepreneurship versus rent-seeking. We also saw the role of sacrifice to Moloch in the Psychopath's rise to power, as well as possible guides to building virtue through the inversion of Rao's dark triangle.

Broad applicability is one of Deutsch's criteria for Good Explanations. I have yet to search for theories that provide alternative explanations to the phenomena that Girard's maps explain, but the reach of his models will be hard to beat. We will stretch them even further in Part III, where we’ll lay out a plan on how to apply what we learned from this journey—both in life and for scholarly work.

Thanks to Raymond Ng, Samantha Law, and Ken Rice for reading and giving feedback on earlier versions of this essay. Thanks to Cleo Kearns for suggesting Salhin’s and Graeber’s On Kings, to Meshach Thomas for the TLP △ and to Ariel Bamar for the Balaji △.

> There are people whose calling is to play the game of power. Most of us, however, are kings and queens in small domains: we head families, teams, or volunteer organizations. I want to know how a good sovereign operates in the modern world. How do you establish, grow, and protect your sovereignty? How do you deal with other sovereigns, both good and bad ones? What's the playbook of a good king or queen? Can we build it by inverting slightly sociopathic playbooks like Robert Greene's The 48 Laws of Power? This would be an interesting future exploration.

As king of a small domain (company of one), I’m interested in this question as well

Where else have you explored this more deeply?