It turns out my country isn’t what I thought it was.

In May of 2022, my countrymen elected Bongbong Marcos as president. BBM’s father, Ferdinand Marcos, was the villain of the world I grew up in. And now, the son of the dictator is the choice of the people.

This is very perplexing to many of us in the Philippines.

I had conversations with BBM supporters, including some friends. The most common explanation — that they were victims of disinformation — just didn’t compute. It felt like there was something deeper going on.

This is an epilogue of Triangulations, a series of crossover essays between the ideas of French social theorist René Girard and the extremely online thinker Venkatesh Rao. As I mentioned in the plan for this season of Explorations.ph, our eventual destination is to view Philippine history and culture from new angles. Let's use some of the models we encountered and developed in Triangulations to examine power players like the Marcoses, the country's polarization, and the Girardian response to these forces.

1. Kings and Egregores

In "The egregore passes you by," the neuroscientist

explores the possibility of intelligences that emerge from groups of humans. He calls this a "group mind." He says that today's scientific community does not yet have a well-accepted theory of consciousness (David Deutsch says the same thing in The Beginning of Infinity) and makes this scientifically prudent statement:All to say, if you ask “Do we have strong scientific evidence that group minds are possible?” the answer is no. But from a “Do people in the academic field seriously consider group minds to be a real possibility?” the answer is a resounding yes.

Hoel presents several of these theories, from philosophers of mind like Eric Schwitzgebel, who wrote a paper entitled "If Materialism Is True, the United States Is Probably Conscious," to the Jesuit and paleontologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin.

Hoel concludes his essay by highlighting the usefulness of the frame despite its current speculative state.

At a personal level perhaps it’s worth remembering that those feelings of outrage—you know the kind, the ones that fill you with such anger you just have to speak out right now, the kind where you’re summoned as if by strings to contribute your little piping neuronal voice to that huge ongoing mind of the internet—those feelings could not be yours at all. Rather, they might just be a glimpse of something larger and darker passing like a giant out of sight.

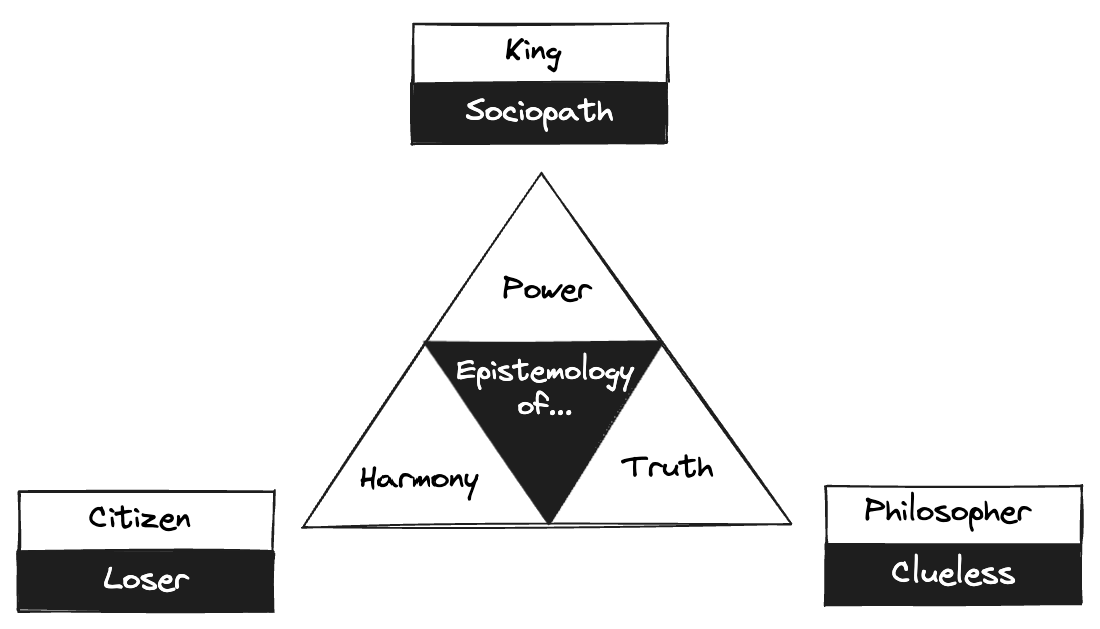

In the triangle that emerged from our Girard x Rao crossover, Hoel, like any scientist, would fall within the epistemology of truth.

Hoel is a good philosopher in our model because he creates a map of reality to help us live better lives. By letting us see these intelligences, he frees us from their grasp. Exorcists know this. To expel a demon, they first find out its name.

What if we look at this usefulness from the epistemology of power? Sociopathic power players would weaponize group minds. This is what practitioners of the occult appear to aim for. They call these group minds "egregores," and their rituals are attempts to commune with these beings. Hoel quotes Dion Fortune, an occultist (emphasis mine).

Occult science, rightly understood, teaches us to regard all things as states of consciousness, and then shows us how to gain control of consciousness subjectively; which, once acquired, is soon reflected objectively. By means of this conscious control we are able to manipulate the plane of the human mind.

In Triangulations II, I speculated that it is through this recognition of egregores and the collaboration with them that power players throughout history have reached the pinnacles of the kingdoms of this world.

For the purpose of this essay, it doesn’t matter whether these egregores are actually real (it depends on how you define “real”). What matters is that it allows us to ask this question: what egregores have Philippine political leaders been collaborating with? The answer will reveal a hidden war in the Philippines that is much longer and much bigger than any presidential election.

2. The Egregore That Reared Me

Egregores shape how we view the world. Let me reveal the egregore that shaped my world by telling you the origin story of modern Philippines I was reared with. I’ll add historical details and screenshots from a lecture by

.Once upon a time, in post-war Philippines, our tutors in democracy, the United States of America, prepared us for our independent journey towards maturity as a nation. They helped bring a man of the people, Ramon Magsaysay, to the presidency. According to Quezon, Magsaysay built a “middle-class republic” founded on Church, clubs, and schools.

Unfortunately, Magsaysay’s presidency was cut short by a plane crash. The succeeding years were dominated by men coming from the old Philippine oligarchy.

One day, a brilliant young man from the north entered the Philippine arena of power. He promised to end the dominance of the oligarchy. He eventually did so by beating them in their own game. His name was Ferdinand Marcos. Like Magsaysay, Marcos won the support of the US by joining its war against communism. Marcos was a genius in the game of power. Sadly, he used that genius to defeat the oligarchy by becoming the supreme oligarch. Like the Austronesian kings of old—the datus—Marcos enriched his family and friends with their parasitic and violent dominance.

Filipinos experienced growing impunity and corruption within the Marcos regime. In response to this environment of injustice, the egregore of democracy, truth, and fair play grew stronger. Many Filipinos gave their lives for this spirit. The tide finally turned after the 1983 assassination of Ninoy Aquino, Marcos’s rival. His martyrdom culminated in the peaceful revolution of EDSA, named after Epifanio de los Santos Avenue, where the majority of the protests took place. These massive rallies were led by the foundations established by Magsaysay in the 50s — Church, clubs, and schools. Marcos was deposed and eventually died in exile. Ninoy’s wife, Cory, was elected as president.

I have an uncle who was there in the 1986 EDSA People Power Revolution, and once in a while, in some of our family get-togethers, he would retell the story to the kids in the family. Our egregore was supposed to live happily ever after.

3. Egregores Also Grow Old and Tired

If this were a film, we would see a transition from a black-and-white memory to the present day in full color, and little kids morphing into adults.

It is hard to believe that almost four decades have passed since the EDSA Revolution. Life happened in the meantime. Like many of my peers, I was too busy with my own pursuits and problems to notice the country changing. In May of 2022, we woke up to a different nation. It turns out that for many, EDSA was no longer the focal point of our history, and its ideals no longer the axis of our country’s unity.

What happened? In the same lecture, Quezon explains the decline and fall of our egregore.

In 1998, the country elected Erap Estrada as president. To the EDSA crowd, he was just a womanizing former actor. We even invented a genre of jokes for him, our equivalent to the dumb blonde jokes of the US. When asked to comment about the Monica Lewinsky affair, he said that both he and Clinton have sex scandals, but he gets all the sex while Clinton gets all the scandals.

In 2001, the old trio of Church, clubs, and schools had had enough after learning about his corruption, and once again came together for EDSA, part II. It was another victory for People Power (pyrrhic, it turned out). The vice president then, Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, was sworn into office at the monument that commemorates the original EDSA, a gigantic image of the Blessed Virgin in between the highway of EDSA, a huge mall, and a gated community for the rich.

Four months later, the supporters of Erap staged their own People Power, which they called EDSA Tres. Mainstream media called them “The Great Unwashed.” The EDSA II folks quipped that while the battle cry of EDSA I and II was “free the country from a thief!” the battle cry of EDSA Tres was “free sandwiches, free juice, and free meth.” One broadsheet commentator wrote, “Isn’t it amazing that in this day and age there still exist undiscovered islands in our archipelago? In early May we discovered one such island: a colony of smelly, boisterous and angry people. They are the poor among us.”

Quezon says that these two latter EDSAs broke the unity brought about by the first one. The poor felt betrayed by the removal of the president they elected. The rich of Manila freaked out after seeing their worst nightmare come to life: an urban insurrection that threatened their properties.

It seemed like the egregore of EDSA still had a lot of life in it with the election of Noynoy Aquino in 2010. Noynoy is the son of Cory and Ninoy. Cory died shortly before the elections, and commentators opined that sympathy for the grieving son helped bring him to the presidency. His term appears to be the last chapter of the EDSA era. The final blow to our egregore happened during his presidency.

In 2015, 44 officers from the police’s elite group, Special Action Force (SAF), were killed in an operation against an Islamic rebel group. When the remains of the officers arrived in Manila, Noynoy was not there to receive them (he was at the inauguration of a car manufacturing plant). This, to Quezon, led to what he calls “The Great Divorce.” According to him, the sentiment of the people was something like this: “We accompanied you as you mourned for your father in ’86 and as you mourned for your mother in ’09. Yet you cannot not make time for us in our mourning.” (The Tagalog “pakikiramay” captures it much better.) Egregores live and die with powerful symbols like this.

In 2016, the Philippines elected Rodrigo Duterte to the presidency. He was the opposite of the ideals of Church, clubs, and schools. He called both Pope Francis and US President Barrack Obama SOBs. He made rape jokes. He was condemned by the UN for human rights violations. Yet by the end of his term, he had the highest approval rating of outgoing Philippine presidents. His daughter, Sara, dominated the vice presidential election of 2022. Her partnership with BBM helped the latter win the presidential elections.

What the hell is going on? Let’s see if we could get answers by getting better acquainted with the egregore in the opposite corner of the ring.

4. The Ancient One

Scholars have noticed these egregores and the battle they have been waging in Philippine history. For instance, below are some excerpts from Kinship Politics In Postwar Philippines: The Lopez Family 1946–2000 by Mina Roces (via Quezon’s Tumblr). Since it is taboo for academics to talk about egregores, she calls this epic battle of titans “a framework.”

This book proposes a framework for such an analysis. It argues that a contest between two competing discourses — traditional social idioms embedded in kinship politics or politica de famila and Western values (here interchangeably used with the term “modern”) inculcated in the colonial period — accounts for these political oscillations.

Roces calls the egregore behind EDSA “Western” because it came from the West. But that’s like saying Marxism is German or that Buddhism is Indian. In Part I of Triangulations, I call it “the Age of Truth” instead because “the West” is more temporal than geographic.

The colonial period introduced a number of Western idioms (the term Western idioms or Western institutions is used for lack of a better term to refer to non-indigenous influences introduced externally into the society from the West from the 16th century onwards) which were eventually incorporated into the cultural milieu and thus of political behavior.

Roces then gives three examples of these idioms or institutions we got from the West. She uses the dense and abstract language that academics like, but she merely describes some aspects of the Age of Truth.

First, a new set of ethics and morals, introduced in the Spanish period through the vehicle of Catholicism, provided a novel standard with which to conduct and judge behavior, often intruding into the established methods of comport.

Secondly, bureaucratic professionalism inculcated in the American colonial period emphasized a different method of participating in politics and business — that of utilizing impersonal norms, the assessment of people on the basis of achievement, and maintaining objectivity in major decisions involving personalities.

Finally, the concept of loyalty to a nation-state, an entity far surpassing the specific confines of the family or village, began to emerge as nationalist ideas spread throughout the archipelago from about the second half of the 19th century to the movement for independence in the 20th century…

In Part I of Triangulations, I presented a Girardian interpretation of the origins of the West or the Age of Truth. Societies tend to side with the strong. The Christianization of the West inverted this, leading to society's preferential option for the weak, which has led to the powerful being subordinated to the truth. Societies based on truth will tend to outgrow societies whose peace is based on the scapegoat mechanism. Societies based on the truth of the natural world (e.g., science and engineering) will outgrow societies that explain the world with myths. Societies based on the truth of justice will outgrow those based on power.

The old egregore, however, will not go down without a fight. In fact, it is still quite strong in the Philippines, and it rewards its collaborators with untold riches. As anyone on the ground can see, power still tends to dominate truth and justice. In the academic language of Roces,

Traditional, or pre-European, political organization is seen as being based on the politica de familia or kinship politics. This concept is used here to mean political process wherein kinship groups operate for their own interests interacting with other kinship groups as rivals or allies. Politica de famila thrives in a setting where elite family groups and their supporters compete with each other for political power. Once political power is gained by one family alliance, it is used relentlessly to accumulate family wealth and prominence, pragmatically bending the rules of the law to gain access to special privileges.

Unveiling the egregores that shape how we see the world allows us to imagine what the world looks like to those on the other side of this invisible war. For instance, to those of us reared by the egregore of EDSA, Ferdinand Marcos was a thief, a cheat, a monster. To those brought up by the ancient egregore, Marcos was a great king. He was Apo Lakay, the supreme datu who outplayed all other datus. Likewise, more than the modern “Western” ideal of “public servant,” Erap, Duterte, and BMM were supreme datus crowned by the Filipino masses.

5. The Long Game

Right before and after the victory of BBM, I saw some viral social media posts from young people on my side of the war. They publicly disowned their parents who supported BBM. The most famous is this open letter from a senator's son, published a few days before the elections. It is worth quoting the first two paragraphs to get a feel of the tension and drama during that time.

I’m writing this weeks after learning the news that my mother, a woman named Loren Legarda, is running for senator on a slate led by a Marcos and a Duterte. She is endorsing fascists. For weeks I have been crying every day, screaming every day until I spat out blood. The decision she’s made is so profoundly unthinkable, unconscionable, unforgivable. In the last month, my entire life has collapsed. It is beyond a nightmare. I still cannot believe it and will never be able to accept it.

For weeks I have been paralyzed in pain. But I have no choice but to publicly declare that I am absolutely disgusted by my mother and what she has decided to do. It sickens me and makes me want to die. I need everyone to know that Loren Legarda lost her son forever because of this. Paint her bright red with that shame. Don’t let her forget it. In the words of a wise woman: I don’t know her.

This shows that even commitment to egregores from the Age of Truth can become a kind of possession. I have been apolitical for a long time: the last time I voted was in 2004. Yet, I can empathize with being possessed by a spirit. I mentioned in Part III of Triangulations that I am prone to the idolatry of putting my muses over the people around me. The act of creation can feel so magical that there's always that temptation to exchange my relationships and my health for creative glory.

Muses and egregores both promise an empty paradise. Even if the Philippine government did become more (or stayed) corrupt under BBM, it was not the end of the world. If Leni Robredo had won, it is unlikely that the Philippines would have radically transformed. History tells us that there are no shortcuts; we have to play the long game. These binary extremes of heaven and hell are part of the lie that leads to possession.

René Girard spent his scholarly career studying and exposing what may be the most ancient egregore, the scapegoat mechanism. Erik Hoel's scientific prudence leaves open the possibility of egregores actually existing. In practice, you either live as if they exist, or they don't. The latter was Girard's choice. He called this choice “political atheism.”

describes a political atheist as someone who sees "the mimetic entanglements around him for what they were, and who could then make a more intentional choice about which currents to swim in, rather than getting swept away by the riptide." He expounds:The implication of political atheism is not that one should be unconcerned or uninvolved in the important political questions of our day. But we should step back and see the mimetic layer of behavior driving our divisions, real and imagined. This understanding might be the first step to transcending the logic of rivalry that our country is mired in.

As I mentioned in Part III, writing Triangulations made me decide to start voting again. It crystallized my commitment to the Age of Truth and its institutions. It also allowed me to see the world through the eyes of those who play the game of power and those possessed by the egregores of this world. I pray that I can follow Girard in his political atheism, and I hope that this will allow me to understand and be friends with those I disagree with, and to be free from the possession of muses and egregores. This is the long game.

Thanks to for helping me shape this essay for a wider audience, and thanks to for help with its 2022 version.

Fascinating, lucid and rich exposition of a complex history!